!li I 1934 1 AND VEGETATION SYRACUSE,

advertisement

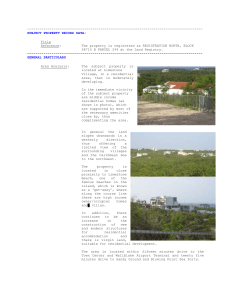

L’rbort Ecolog_v. !li I 1934 1 99-l Elsev~er Science Publishers RESIDENTIAL 25 B.b’.. 99 Amsterdam Printed N .A RICHARDS. .\BSTR J R 11 hlay N A.. space and MALLETTE, R/J. SIhlPSON and State E A. MACIE L’ni~ersrt_y of New \‘ork. I 193.3 hlallette. snd tracts in Variation in dlvldual lots. tracts. total while highly tiiied back hood. number this >;rrds stud>. ol’ lots odtxcnt tree limited resources crogeneous. or lot and and lot ot’ the are= Among and canopy area and enamlned and show more or little on lots care oi public managed pattern lots streetsIdes and Thlj ten only especially tracts garden to oi The greenspace were compared documents resource the areas. the end with iden, side. and neighbor. trees. the a large. on LBTI, the (actors in front. to lawn \rlth Rlost 111. within correlated orientations study and blocks. be attrthuted vegetetlon selected characteristics components. and green, 99-l 25. heterogenetty components Intel’ests residential in tracts. highly among 01’ resident 8: lots to IS Ecol.. phystcal greater and greenspace greenspece In greenspace tracts 3110 cannot personal thr have Residentus L!rhon residrntlal groundco\er. 3s evidence Ion. adjacent other 19h4. attrtbutable pa\tng to E.-A.. York Lariation equrllly and Shrub. l‘eatures compoilt practkally about 4b’: their attributable Dlstrihutlon uere species to lots neighhors. eluding IS on identify structures variation area esamined to size ot’ relatlonshlp Indlvtdu;il In tree In lot R.J and hlacle. Syracu;e. New. tit! were NY areas substantkl greenspace ation vegetation Syracuse. ltttle Simpson. in 3 mature residential and shows . J.R Legctation Creenipace census are LN A MATLJRE CITY: ACT Richards. tirea Netherlands NEW SORK College of Enlllronmental Science and Forestp, Syracuse.AV\’ 132/O 1U.s.4 I I Accepted in The AND VEGETATION GREENSPACE SYRACUSE, - in. more bet, resident131 lots in Syracuse INTRDDLtCTION hlost investigations of on public space, especially urban greenspace and vegetation have streetsides and parks. The predominantly focused private greenspace associated with urban residential properties has received little study even though it may he the most important greenspace in the dail) lives of urban residents. Urban open space inventories for planning purposes often ignore residential greenspace. although it may equal or esceed the open spaces inventoried. Few aerial photo interpretations of urban greenspace and vegetation have heen done at sufficient dettil to discern the intricate interspersion of residential greenspace with structures and paving I hlarotz and Coiner. 1973). One of the few urban tree inventories to include residential vegetation \vas by Last et al. (19’761 for Edinburgh, Scotland. lots, They reported Indicating the that importance 815 of of that city’s residential trees were greenspace on resldentwl and \,egetation there. At least greetxpace: two reasons ran be Identified for so little study of residential it IS recognized to be estremely diverse. and therefore difficult to study: and. ‘and decisions. cisions relating generally. it has not been a direct subject of public poliq Hotvever. this resource certainly 15 impacted tq. public deto residentinl life in a city. Also, the assets and deficiencies of resiclentlal greenspace and vegetation should he considered in managing the pu Mic-sector greenspace. because these obviously interrelate in both the physical ‘and social systems of cities. Our is part study of residential greet-space and vegetation in of R continuing cxase study of the total greenspace Syracuse. and N1 VegetatKJll resources of the city: theu- character. distribution. value. ‘and management. Part of this research has been the study of the city’s greenspace subsystems: institutional. residential and commercial identified as streetslcles. parks. greenspace. and street resources tree lands. vacant This streetside netbvork the other subsystems. we re‘alized \‘eDr early. to study because Intensive \vas completed of the study of the streetside I Richards first and space and Stevens. 19791. provicles a useful matris upon which to relate Research on the other subsystems is continuing. that residential greenspace was the most difficult great number of individual lots and managers in- volvecl. IVe clistinguish between greenspace. the space capable of supporting and the vegetation actually being supported there. For this vegetation. study, greenspace is described planimetrk4ly as soil surface area capable So defined. greenspace is determlned by subof supporting 1:egetation. tracting the areas of structures and pavmg from lot areas. Herbaceous and shrub vegetation effectiveI>. occupies greenspace surface area. However. can estree boles u3ually occul~y negligible surface area. but tree crowns tend over structures and paving as dell as other vegetation. Therefore. tree crowns must he described at a different level. inclel:Jendent of greenspace dimensions. Our studies to date have not aclclressed the estenwe and I~JcJssi My ii nder other spread of tree roots under the greenspace wrface. surfaces. but thlj 15 indicated by other tree dirnenslons. The primm’ objective of this stucly was the cletailed characterization of resiclentinl greenspace and vegetation. and their variability in the city. \Ve sought this informatIon both to contribute to our evolwng model of in Syracuse. and t0 test InetllcJdolcJg that might greenspace resources be useful mined by both local 111 other cities. Residential greens~:Jace a.reas are strongly cleter. the initial layout and development of residential l(ltj: reflecting topographic constraints ancl clevelol~ment patterns at that time. One ivould espect that greenspace uses and reflect mcJre of the individuality of residents toward groulJing pothesized that tenclencws vegetation wlthln lots might over time. However. we hyof residents sharing similar 101 social characteristics. along with the initial factors of lot layout and de- velopment, might result in less variation in residential greenspace characteristics within neighborhoods or within blocks than among different residential areas of the city. Our study was designed to test this hypothesis. Knowledge of the levels of variation in greenspace characteristics is needed for effective IJ Infeasible sampling to take of these resources in a city. because generally, it a large sample or complete inventory’ of residential greenspace at a detailed level. We also had a more qualitative hypothesis that physical evidence of the treatment of residential greenspace and vegetation indicates residents’ revealed preferences toward these resources and. therefore, may be more realistic than of residential direct surveys of attitudes ‘and values. Because greenspace and vegetation are mised with many the values other indi- vidual and neighborhood values associated with residential life, the treatment of greenspace should mdicate priorities actually given to this resource. Our was interest beyond was in the information the hcope of this study content of the physical evidence; it to relate this to espressed attitudes or detailed social characteristics of residences. One interesting aspect of urban residential as xe predominant potentially espress in Syracuse and many three faces: social lots other front with detached communities. yards suggest houses. is that the the) interaction of residents wlth the neighborhood; side yards may express more direct interactions between adJacent residences or other adjacent land uses: and back yards may tndicate a more individual orientation as well as interactlon with neighbors. The physIcal evidence of the relative treatment of front. side, and back yards should give clues to the social orientation of residents in their greenspace use and management. Alternatively. full retlectlon of resident orientation might be blunted by inertia, to the estent that residents may accept the status quo in their residential greenspace and vegetation unless they are dissatisfied enough to change them. However. changes do occur over time. Schmid 119751 described the transition from ‘open’ to ‘closed’ residential landscapes over time in the prairie environment of Chicago. Our study sought to identify what differences in the residential landscape within Syracuse. STUD\’ might have evolved in different neighborhoods SITES Syracuse 1s one of the eastern-most cities arising Prom westward expansion of the post-colonial llnited States. Initially settled about 1800 around a salt industry from lakeshore saltsprings. Syracuse grew to be chartered as a city in 1848, prlmaril>V because of its situation in central New York, IInkIng the Erie Canal with easy north-south transportation routes. The city only has moderate topography. total local constraints to development relative relief due to steep of about 100 m. and slopes. Syracuse grew rapidly with moderate industrial development from the mid-1800’s the 1920’s; reachuig a peak population of over 200000 m 1930, through through both growth and annexation. Since 1950. the city population has declined as growth has shIfted to the surrounding metropolitan area. Today. Syracuse is a mature city of 170000 populatlon, undergoing continuing internal change as the center of a maturing metropolitan county of 470000 populatlon. We consider Syracuse a good. medial case-study city for the northeastern Llnlted States. For the study of residential greenspace. we selected ten census tracts from the 53 predominantly residential tracts in Syracuse. escluding from consideration ten tracts with mostly non-residential landuse. Census tract boundaries do not necessarily coincide with neighborhood or developmental boundaries. and generally recognized neighborhoods in Syracuse each encompass two or more tracts. Therefore, of recognized residential neighborhoods were basis of predominant development age, lot tracts representing chosen. primarily size. and housing type a range on the as oh- served during the previous streetside study (Richards and Stevens. 19791. llse of census tracts pen-nits comparison of standard census data. which also influenced our selection of tracts tTable II. The study tracts encompass 18’; of the 1980 population and housing units. and l-l? of the area of the city including its non-residential tracts. Syracuse predominantly has detached, wood-frame. one-to-four unit residences on private lots. hlost housmg is 30-80 years old, and about 10’; of the units are owner-occupied (Table I). In spite of a 147 decline in population oi’er the last decade, the city has had a slight increase in housing units because splitting of residences into additional units and neb apartment construction has counteracted building demolition. This is in line with recent urban changes throughout the northeastern llnited States. as the average number of persons per household has declined. The stud] tracts contain few of the larger multi-unit dwellings in the city. many of which are in predominantly non-residential tracts where median household incomes tend to be low. Therefore. compared with city’ averages, the range of study tracts is skewed toward single-unit, owner-occupied homes and higher median incomes. This reflects our intentional focus on residential areas. rather than on all residential conditions in the city. Housing units in commercial areas typically have little residential greenspace, whereas the more institutionalized greenspace associated with large, multi-unit dwellings warrants separate study. Figure 1 identifies the location of the ten study tracts in relation to the current boundaries. the Central Business District, and the areas developed as of 1908 - roughly differentiating the older and newer parts of the city. Some of the range in residential patterns are illustrated in Fig. 2. Briefly characterizing the study tracts in order of age, 23 is in a marginally residential area near the city center; 6 and 27 are in old areas with strong neighborhood and ethnic identities; 54 is undergoing deterioration 103 104 and loss of housing. and change in racial compositlon; and 51 is in earl) stages of similar change. Tract 45 is in a slightly newer, university-impacted area; 3 is characterized by one-family homes on small lots; 19 by slightl) larger lots but more multi-unit dwellings. The newest tracts. 61.3 and 48. have mostly suburban-type development of smgle family homes on relatively large lots (Table STLiD\’ RlETHODS I). The study was conducted in the late spring and summer of 1980. In each census tract studied. we random-sampled one out of every sis blockfaces that contzuncd at least three residential lots. One tract was sampled more intensively before selectwg this sample of blockfaces. \\‘ithin each sampled blockface. evev third lot. starting randomly. was studied in detail: ivith the further conditions that no less than per blfJckfaCe were sampled. and that these tivo or more coldd include than four one but lots not both comer lots. This resulted In about 5% sample of residential lots within the study tracts. Because resident permission for access to lots was required. failures to get this forced some shifts in the sampling pattern. However. were fe\\. this should not have caused a significant bias. because refusals fig. 2. Residential patterns on relalively large lots tracl~: 141 tract 6. mostly in Syracuse. Reproduced from color mfrared photos. scales approximately equal. Portions of three study census dwellings. 10 tract 61 3. mos.tly 1-unit dwellings 2- -I-unit dwelling> on zmall lot>: (B) tract -15. mostly I--2.unit and repeated visits eventually reached people 487 residential lots on 171 blockfaces about 105 mandays of field work. were at most studied, residences. requiring In all. a total of Our basic unit of area for recording field data was set at 9.29 m’: a 10 ’ 10 foot square convenient for translating foot measurements. This unit wa5 selected as practical for on-ground estimation of vegetation areas. and a a bakance between the time demands of smaller units and the loss of detail in larger units. We sought to identify more interspersed detail than has usually been obtained in studies of urban greenspace. Lot boundaries ivere tape-measured to correct errors in city maps. Building dimensions and its location on the lot were measured, and the number of residential units. condition of residences, and area and type of other structures were recorded. Areas of paving and g-reenspace types were estimated in 9.29-m’ units . so that the total equalled the measured lot areas after subtracting the structure areas. Scaled sketch-maps were used to aid in accounting for .alI space in each lot. Front, side. and backyards tvere described separately a3 to paving area and type, and greenspace areas in lawn, shrub. g‘artlen. ancl other cover. The geenspace areas were further detailed by use and care classes. as described in the results. Trees in the yards were not Eissigned greenspace area. but rather were recorded by numbers of stems. species. diameter b.h. (at 1.4 m), estimated tot&al height. and height to the base of the cr0ir.n. The tree crown canopy area and at its widest translating plane this was determined to circular area. The by estimating entire crown the average radius area of trees In the yards was inclucled regardless of whether it estended beyond the lot. Because overhanging crowns from trees outside the lot were not counted, this \%‘a5 felt to t.ompensate in determining crown area coverage on the ~amplecl lots. \i’e ‘also collected clata 011 the greenspace area and trees on the public streetsIde strip adjacent to study lots. to compare the residential ancl streetsIde space and tree resources. Some of the tree data were collrctrd ft_)r a more detailed study of urban tree crowns. reported separattll>’ 1,. hlallette I 1982). Among other findIngs. hlallette confirmed that our e3iniation of horizontal crown area a5 circles closely approslmated a.reLx obtalned by more detailed determination of their irregular 4~al’rs. .A minimum of 97 in format ion bits \\err recorded for each lot. The 5tucl!. 1~35 designed to use analysis of vanance to partltlon the variation founcl in all quantitative data among census tracts. among blockfaces within blockfaces (sampling tractts Iespi-rimentsl error’), and among lots lvithin error). Bec*auje errors in the data collection are believecl to be minor. the error terms obtatned can he attributed primarily to actu,al variation at thrse le\,els. for cles~:ript i\e Qualitative pi t-pose%. data were simply summed for each census tract 1(J; RESllLTS Quantrtatioe characteristics of residential lots Our major quantitative hypothesis, relating to the variation of residential lot characteristics among and within study tracts, is tested by the analyses of variance summarized in Table II. The high significance of F values for most variables is not surprising because of the strength of the experimental design. The proportions of the variation attributable to census tracts, blockfaces within tracts. and lots within blockfaces. are of greater interest. Collectively, these analyses confirm the value of our three-strata sampling of tracts, blockfaces. and lots. But they suggest that fewer blockfaces could have been sampled. to reduce fieldwork without impairing our findings. The means and standard deviations for data from all sampled lots permit comparison of the total variation found among lot characteristics (Table II). Figure 3 illustrates the mean lot areas sampled in the ten census tracts and corded, but this fqure. TABLE their mean the variation proportions within tracts in must the various be considered components re- in interpreting II I’ariation In characteristics \‘ariable of sampled Percent lots of total variance attributed toa All sampled lots Llnlts in studb, Block tracts In tracts block Lot area 36 Lot width 31** Lot length 9 ** Residence Other Lawn Shrub tree ** 1; ** j iaces hlean S D. 618 193 16 ml 39 39 10 ml 62 121 -16 rn’ $2 24 23 rn’ m’ ‘21 ** 79 91 43 26 32 271 229 ** 9a 12s 2.2 * * rn’ 5 30 rn. 86 32 22 29 25 Im’l (m’i 67 55 9’: (m I I I 1 1 1 frn.1 20 numbers area ** 26 *I 12 ** 20 ** 54 6b 21** 9 ** 8 *’ -13 ** Id ** 17 ** 36 73 75 5.2 151 7.4 18l!i Irn’l st reelside greenspace area numbers tree canopy ‘From 5” in trees tree canopy Adjacent -II 2 11 ** 0 11** area 36 ** 2,** 13 area cover 29 ** 25 1_I** 0 area Residential tree area area area Garden Other area structure Paving ** faces Lots Census analyses area of Numbersoiobservations variance: **qnlficant In analyses. F at 10 census 30 0; 40 0 01 tracts. level . s significant 171 blockfaces. 20 0.h (m.l 75 ( m ‘I F al 0.10 478 101s level Residential tracts. and lot area \\a~ taken also \vas espected to into account affect other in lot selection of characteristws; the stud) so this is the independent varlnble against which the other data is compared tTa. Me 111. i’ariation in lot area is about evenI>. partitioned among tracts. blockfaces. and individual lots. This indicates some unlforn~it)p of lot size within tracts and also within blockfaces. but not strong control at either level. hlean lot ‘area for tracts range from 13-l to 1032 ml. The two newest tract5 clearly average iarger lots. hut mean lot size of the other tracts cloes not follow the orcler of their development ages I Fig. 3 I. WIthIn the lot climensions. variation in lot ~itlth is similar to that of lot areas. Lot length. or depth. 15 largely controlled by street layout and consequent bloc-k size. w more v&Ant IOII 15 at tnlwtalAe to the blockface Ie\,el. The weak control of lot lengths at the tract level suggests that the layout of blocks ha vaned less throughout the city than has their sub division into lot$. the resiclence depends on Iwllcllng design. The lot area occupied I+ was built for single or multiple-faniil inclucling whet her the structure occupancy’. The \,ariation in rr~idence area IS mostly attributable to the individual lot lei,el. and indicates the heterogeneity of house sizes throughout Syracuse. Residence area is not very closely relatecl to mean iot area among older tracts. tracts. partly because Residence area there data on are more the multi-family residences in two newest tracts are distorted whereas the separately recorded, by inclusion of many attached garages, detached garages are more common in older tracts. When areas of detached garages are added to residence areas, differences among the tracts are further reduced. Variation in are&as of other structures on lots, primarily detached garages, is not significant among tracts and is largely an individual lot characteristic. Similarly. the area of paving is a highly individual lot feature. averaging close to a constant area across tracts. The significant control of paving at the blockface level probably which affects the length of walks and driveways. Creetlspace The among results from lot length. areas mean tracts. ranges from 195 to 793 m-’ greenspace area of lots. which is determined by subtracting the mean residence, other struc- ture. and paving areas from lot areas (Fig. 3). Because mean areas of structures ruid paving vq less among tracts than do lot areas. mean greenspace areas range from 13 to 77S of mean lot areas among tracts. This confn-ms the espected: larger residential lots generally have greater proportions of greenspace, but greenspace lot areas unless the are& of are&as cannot be estimated structures and paving are from residential also considered. A companion study compared the accuracy ncl utility of large-scale (1:12 0001 aerial photo interpretation with detailed ground truth obtamed in this study ISimpson. 19811. Comparing color and color-infrared photos taken IN late summer 1980 with our ground data m Tract 19. Simpson concluded that lot and structure areas could be accurately measurecl on either film type. Hoivever. areas of paving and various types of greenspace were more difficult to identify and tree crowns. Paving area because probably of visual interference could he determined by txuldings better from photos taken in the leafless season. but more detailed informatmn space features requires substantial on-ground sampling. Among the vegetation components of lot greenspace. only shoivs more variation attributable to tracts than to individual on greenlabvn area lots tTa- hle 11). Mean lawn area increases diq~roportlonately to total greenspace area. so mean lawn proportions range from 52 to 80% of greenspace areas among tracts (Fig. 31. In contrast, most variation in shrub area is attributable to the individual lots. Although some relationship between shrub and total greenspace area is suggested, the tracts bvith the most greenspace tend to have a lower proportion of their greenspace in shrubs. Areas of other cover Include non-lawn groundcover vegetation and bare soil resulting from sampling or tree shade. Most vanatlon in other cover area is attrlbutable to individual lots. and the proportions of greenspace area in other cover show no pattern among tracts. Variation in garclen area is overwhelmingly at the individual lot level. and is non-significant among tracts. 110 The vanation among vegetation components correlations between geenspace area and the ponents on individual lots in each tract (Table is further examined tq areas of greenspace comIII). Correlations between lawn and total greenspace areas are highly significant in all tracts. and they esplain most of the variation in la\vn areas on individual lots. Howe\:er. correlations between shrub and total greenspace areas. and between other cover and total greenspace. are significant in fewer tracts. and these generally individual are esplain less than lots. Correlations non-qnificant to one unusually arninrd correlations separately In front. to the TABLE \‘s,.lahles correlations in most large half of the variation in these components on between garden and tot&al greenspace areas tracts. garden and and the best lot sampled correlation in that tract. is attributed We also es- between total greenspace are% and their components side. and back yards tno table). Results are similar for the combined yards. but vav Range 01 more ;miong tracts. Ill Numberot’trxts ilgnificint uith correl_atlonsd r \aiuesb .Acrosj the study tracts. lawn area tends to occupy most of the greater greenspace on larger lots: are* of shrubs and other cover are only weakI> related to greenspace area. and most ianatlon must be explained by other factors. There 14 generally little relationship between garden and total these findings in terms of equal greenspace areas among lots. Esprewng with larger lot3 have more total area of residential blocks. neighborhoods dlfference 111 total areas area in la\\-ri5. less In gardens. ruid no consi3tent of shrubs and other cover. Considering the heterogeneity among lots and also the more diverse character of shrubs. gardens and other cover than it appears that the dwrsity of vegetation misture is greater in of lawn. 111 neighborhoods with smaller lots even though there 1s more greenspace in larger-tot neighborhoods. Our findings on residential greenspace in the study tracts appear to provide a reasonable basis for characterizing this resource throughout residential areas of Syracuse. Combined with other information, they permit within preliminary the total estimation greenspace of the proportion resources of the the also of residential greenspace city. Total greenspace in Syracuse was previously estimated from 1972 aerial photos as 58% of the city’s area (Richards. unpublished. 19791. This had probably changed-tlttle 1))’ 1980. For the ten census tracts III the current stud)‘. estimated total greenspace ranged from 41 to 765, of the tract areas. showing an increase from the inner city outward but also reflectmg the location of parks and other large greenspaces in the city. The average for these tracts. weighted by tract areas. is 6OY greenspace. Applying the present residential findings to the earlier total estimates. we estimate that 62’; of the total greenspace in the ten tracts is residential. Using information from several sources along with this study. we derive a preliminary estimate that residential greenspace constitutes about 485, of the total greenspace in Syracuse. For comparison, we estimate that the city’s public parks contain about 9? and the public streetsides about 7T of the total greenspace. Refinement of all these estimates awaits better mformation on institutional. commercial and vacant greenspace in the city, but it is evident that residential greenspace is a prominent part of the total resource. Resider1 tial It should trees be recalled that trees were not included in the greenspace areas. but rather. were counted and their overhead canopy areas estimated on a separate plane. Tree canopy area is more useful than tree numbers for examining the impacts of trees on residential areas and can be estlmated from appropriate aerial photos as well as from the ground (Fig. 2). However. tree numbers are valuable complementary data for calculation of average canopy area per tree, as an indication of tree sizes and the threedimensional impacts of trees on tots. Among tracts, there is a rather wide range in mean number of trees per lot, and a slightly narrower range of crown canopy area (Table IV). Compared with the variation in lot areas, however, less variation in numbers of trees per lot is attributable to tracts and more is attributable to individual lots (Table II). Variation in crown canopy areas is even more attributable to individual tots, because of variation in tree size. Comparing the mean tree canopy areas with greenspace areas among tracts, the resulting ratios range from 22 to 62R, canopy to greenspace, and give an indication of the relative soil areas supporting the tree crowns. However, the tree crowns are over structures and paving as well as greenspace: so the ratios of canopy area to lot area, ranging from 11 to 33% 112 among tracts, are better indicators of the residential tree cover (Fig. 31. However, mean proportions of tree canopy cover on lots are not consistently related the two most to mean lot sizes among recently developed tracts tracts. A partial explanation with large lots average more. is that smaller trees; suggesting that much of their tree cover is not yet fully grown. Older tracts tend to have more mature trees, but tree cover may have been more deliberately restricted in the tracts averaging small lots. Correlations of tree canopy area with total greenspace area on individual lots are highly significant in most tracts, but these account for less than half of the variation in canopy area on lots (Table III). Consequently, much of the variation in t,ree cover among both tracts and lots remains unesplained by this study, and apparently reflects more complex factors of community history and individual choice. TABLE Trees I\’ on residential lots and adjacent Range Tree numbers Tree canopy per lot area 1m ) Tree canopy areas area> census Residential lots Adjacent Range Median Range 1 9-14.3 0.3- 3.9 1.0 “G-99 1 :3- 4 3 b ‘I’l--r;‘, 36 ratio- Range hledian 9.1-1r 1 3.1-24 1 2 l-10 1 10 33-24; tracts streetside< Rledian .3I‘J 2% (7 numbers among 11-_;L’ Canopy/Ereenspace Greenspace median 118 (rn.1 1rn.l Tree and 54-‘29.5 51--3; 195-_; 93 Canopy area/tree Creenspace area ResidentiallStreetside streebides 0.6 24 :y,III “$4 110 1 7 1 .“, 1 Because tree cover can affect other vegetation on residential lots, we also correlated tree canopy area with areas of other greenspace components on lots (Table III). Trees impede lawn growth in Syracuse. but the highI> significant correlations bet\veen lawn and tree canopy area in four tracts are positive. We interpret these as reflecting co-relationships of both tree canopy and lawn areas to greenspace area. Correlations between shrub and tree canopy area are highly significant in only two tracts. and account for lIttIe of the variation in shrub area on lots. Tree cover is inimical to most gardening in Syracuse. but the one highly significant correlation is positive, and is probably due to co-relationshIps with greenspace area. We espected positive correlations betiveen other cover and tree canop] area. because other cover includes bare 3011 and shade-tolerant plants under 113 trees. Of the variables, canopy seven four area, tracts suggest and relations between arately for front, with highly a direct three suggest significant correlation correlations between co-relationships with other between cover greenspace tree cover and greenspace component areas side and back yards are poorer, suggesting that these and tree area. Cor- done septhe green- space components and tree cover are not accommodated by different allocations among yards. Therefore, with the esceptlon of other cover directly associated with trees, there is little evidence of direct relationships - positive or negative - betbveen tree cover and greenspace component are% in the study tracts. trees naturally reproduce and This finding has plausible esplanations: grow well in Syracuse. and tend to fill any spaces in M hich they are al- IoLved to grow. However, generally less than half of the residential greenspace is tree-canopied; so there appears to be a conscious restriction of tree cover on resldentlal lots. This reduces correlation and conflict between trees and other vegetation. The lack of correlation may also result from residents tolerating some conflict between trees and other vegetation if the trees are otherwise valued. Residents to-day have the opportunity for complex flected In simple correlations. .-Idjecent strwtside living with decisions their that greenspace daymay not be re- space and trees \!!e measured unpaved. adjacent public streetside present. these were used green5pace area rather than total area on the strip. In most cases where public sidewalks were ti the practical boundary between streetside and residential greenspace. Legal boundaries are often slightly inslde front yards ‘and not identifiable lvithout survey data; so the legal streetside area may have been slightly underestlmated. Where public sidewalks were absent !n portions of the newer tracts. the public streetside portion was estimated from other evidence. The width of the streetside strip is usually constant for a blockface. and differences tn the original allocation of public streetsicle space can be observed among tracts and blocks. Therefore, some of the \:arlation in streetside greenspace area is attributable to tracts. but more 15 attributable to blockfaces (Table 111. Most w-iation in street tree numbers and street tree canopy area per lot is attributable to the mdiviclual lots. Only part of this is due to variatlon in the Iimitecl streetside space. The relationship bet\veen street tree canopy and streetside greenspace area is ‘also vev ~\e‘ak. as suggested I, the ratios of mean c‘anop~. area to streetside greenspace area. which range from 33 to 247’7 among the study tracts. However. the mean ratios over 1005 In half of the tracts indicate the great dependence of many street trees on adjacent frontJ,ard greenspace for their support. Comparing street trees with residential trees. we found averages of from 3 to 24 times more residential trees runong the study tracts (Table Il’). 114 There is a smaller ratio of 2 to 10 times more canopy area of residential trees than of street trees, because the street trees average larger size. From more detailed esamination of our tree data. Mallette (1982) concluded that the crowns of the larger street trees have been modified more by pruning, whereas large residential trees apparently have had their numbers controlled more than their crowns pruned to reduce interference Hith other residential features. On the other hand. the crowns of smaller residential trees. such as flowering or fruit trees and small commonly have their crowns modified by pruning. to be practical. cost-efficient management responses on residential lots. conifers, more These would appear to control tree cover Tree specres We identified tree species on both the public streetsides to esamine differences L’). The 2500 on residential residential lots and the adjacent in species composition (Table residential trees recorded should be a good sample of species lots in the study tracts. The 315 street trees provide a weaker R;lngti Range and mcdlan hledlan among census Rang*? tracts hlr-dltin 115 basis for species comparison. so we tested the accuracy of this sample against the 1005 inventory of street trees taken two years earlier (Richards and Stevens, 1979). The proportions of the most common species in our street tree sample compare very closely with the 1005 inventory. but as would be espected, less common species are sampled less accurately. Residential trees include many natural volunteers from local seed sources, as well as transplanted wildlings and commercial street trees are uncommon, but an estimated 35’; trees and probably a higher proportion jacent residents - often using transplanted nursery stock. Volunteer of recently planted street in the past were planted by adwildlings (Richards and Stevens, 19’i9). On the other hand, city plantings of nursery stork include more exotic street tree species than are commonly available to residents. Maple is the most common genus on both residential lots and streetsides in all study tracts. but the genus as well as the major species. Norway maple, constitutes a higher proportion of streetside than of residential trees in nine tracts. There is also a higher proportion of silver maple in the streetside samples of seven tracts. The data on sugar maple is inconclusive. but boxelder appears to be more common on the residential lots. Norway maple is naturalized and volunteers freely in Syracuse. Residential discrimination against this species is indicated. probably because of its dense shade and heavy leaf litter. The native silver maple has lighter foliage, but there may be discrimination against its vigorous powth and large ultimate size on residential lots. Sugar maple is the major native species as well as a popular shade tree throughout central New York. It volunteers less than the other maples in Syracuse, and also its rather large size and dense crown may discourage its use on residential lots. Boselder \:olunteers freely, and may be accepted moderate size and crown-density. The connotation of the term more ‘shade on residential tree’ is not lots because entirely of positive its in Syracuse. The normal daily maximum temperature is above 25°C onlh 109 days per year. from mid-hlay through August; and there is an average of only 635, of the possible sunshine during this. the sunniest period of the year. Shade is undesirable for a greater portion of the year. ancl the visual and other benefits of trees are more significant. Increased interest in solar supplementation of home heating may cause further discrimination against residential shade trees in Syracuse. Conifers can be useful on residenrlal lots in Syracuse for windbreaks and green color in Lvinter. but are generally unsuitable as street treer; here. Spruce is the second most common genus. affter maple. on the residential lots sampled; only a few were found on the adjacent streetsides. Norway spruce, P~cea abres, 1s used most for Lvindbreaks and screens. and blue spruce, P. prrngens. is more common as a specimen tree. The ‘cedars’, prilots marily Thuja SC>. but also Juniper-us sp.. were found on residential in all tracts, but not on streetsides sampled. Pines. mostly white and Scot5 were found on residential lots In nine pine, PIIIUS stroblrs and P. sylveslris. tracts. but none were on the streetsides sampled. 116 Species of the Rose family. especially cherry, plum. apple and pear. were found on residential lots in nine tracts, but on few adJacent streetsides. Some species volunteer in Syracuse; most ornamental anct fruit species are more practical on residential lots than high maintenance needs. The native elms were vey popular street before the advent of the Dutch elm on streetsides because and residential trees in Syracuse disease in the 1950’s. of thelr because their high crowns and light foliage caused minimal conflict with other urban features. N’e found elms persisting on residential tots in eight tracts but on few streetsides sampled. Some residents: most are wilcl volunteers of the elms are being maintained which. along with the volunteers 1)~ in parks and other area. continue to keep the dise&e active. This is of concern in management of the disease to permit limited use of elms again in the city (Lanier. 1982). The other listed genera. found on sampled lots in at least half of the study tracts. appecu to be more common on residentA lots than on streetsides. Some tree species are widely promoted by mail-order nurseries for residential planting. but are generally poor for urban lots: for esample. becau_se of rank growth; and various willows and poplars. Popuhrs q.. ‘white’ birches. Betula 513.. because of destructive Insect pests. Only a fe\!, trees of these species were found on residential tots: none on the adjacent streetsides. In all. 31 tree genera were recorded on the residential lots. and 14 genera on the streetsides. This apparent dlfference in divenit> may result partly from the smaller number of street trees sampled: ovet 40 genera were recorded in the previous 100? inventory of street trees 1979). Several esotic species throughout the tit)’ I Richards and Stevens. that have been planted recently by the city are seldom seen on residential lots. Of these. Giukgo and Zt~/hoi~a sp. were in our streetside samples. In general. the specier; composition of residential trees appears to be Naples predominate less on conservative and practical for its purposes. the lots than on the adJacent streetsides. but also the apparently greatel diversity on the lots is composed mostly of native or l\ell-known introduced species. Recently. many cities have shown increased concern for the regulation of trees on pnvate tots In the public Interest. Our findings suggest that. with the possible esception of emergency measures for control of insect or disease epidemics. there of residential trees in Syracuse. Qualitatioe N’e characteristrcs regard the is little of rcsrdential allocation of justification for public regulation lots non-greenspace and greenspace features runong front. sides, culcl back yards. and the care of residences and of vegetation In yards. as more qualitative characteristics of residential lots. These characteristics can be espected to Show great variation among individual lots. Therefore. most of these data were simply averaged b!- tracts. to com- p,are the ranges of tract means information sought. we decided and that the medians of these means. more sophisticated treatment For the of these data was not warranted. Data on residences and other non-greenspace features of sampled lots are summarized in Table VI. The proportions of single-unit residences recorded in tracts are higher than those reported in the census data. suggesting a bias in our sampling method against multi-unit dwellings and. therefore. also against rental may have resulted from our one-unit dwelling5 T.-IBLE can be units. However. errors, because difficult to identify from residcnttal lots and other. nun.greenspacc* I’CBIUWSOn Range Range Residence and median hlpdisn TV pr one.l’amily residences Ij+.I’atntly Restdence 7; 0 residences condition escellent condition 2 iJ needing minor repair5 64 needtng mator repairs 10 badI>, deteriorated structure3 detached other garages 4rj s and decks swimming plq 2 on loti buildings patto< .j pools and gsmc 1 cou r[s Ct P;1\ ing areas by predominant black top 01’ asphalt concl’ete gre\el or compActed brick 0i in front tot21 ynrd; tn side J erds in hack yards Tencr. I’ront yards side .\cirds beck 1 ard< Tight wire iron1 iettces yards stde yards htick >oil or stone Proportion No discrepanq in formerly outside evidence. \‘I Strurturec Other some of the multiple units !,al,d< pising type Amon@ sampled cettius tracts tn study 1”;: I tract5 The condition of residences was recorded for comparison with the indicated care of the residential greenspace. Housing needing minor repairs can be considered the normal condition in Syracuse. because woodframe structures over 30 years old requve frequent repair. The proportions of houses in excellent condition, and also those needing major repar, range more widely tends to be come levels. involved. among tracts. The average condition of residences in tracts related to census data on owner-occupancy and median inbut some inconsistencies suggest that other factors are also Other structures on cause they are features of the other than added swimming lots. and lots indicate alternative that may be added or structures are detached garages; in the older tracts. Recreational these are being removed structures - patios and behlost more decks. pools and playing courts - are highly mclivldual features among most lots have none of these. This may reflect the city’s climate. the modest incomes of reational facilities within recreational structures. Dlstriblc uses for greenspace. removed over time. t/o11 urld treatmerlt most rejldents. and the many other and near the city. reducing priorities o/‘space in .vards Recording greenspace. vegetation and other side and back yards prowdrs a more detailed Sards are defined by the to the sides of residences. outdoor recfor personal features separately view of residential fur front. lot use. location of the residence: side yards are adjacent Residential lots In Syracuse normally have t\vo side J.a.rds of unequal l\.ldth. One side is usually occupied I~). a drivtway: the other side may have more greenspace. depending on the lot and house iridth. Il;e use the dibtrlbution of greenspace among yards as the basis for comparing the distribution and treatment of otherf’eatures in the yards. The metllan and 62’; of In 257 back of yards the preenspace reflects surprising in front yards. uniformity 1-L”; In side yards among most tracts (Table \‘111. .\pparently. a rather consistent pattern of positlonmg houses on lots has been practiced in Syracuse throughout its histow and Independent of lot bizt’. Other houbing pattems not common in Syracuse. such a5 houses close to the street. semi-attached or rot\’ houses. or more recent cluster housing result in different dlstrlbutlon~ of greenspace among yards. and Its distribution among We were interWed in the type of paving. yards. becsuje of its effect on bvaterprooflng wrfacnes. In all tl’acts. the or asphalt. clriveways and concrete must Common pavings are t:)lacktop. such as brick. stone or gravei. are less slcle~valks. hlore porous pavtngs. common (Table \‘I\. CombmIng the distribution of paving and other structure areas and of ~~eenspace among yads. a median of 45% of the side yard area between houses is covered with mostly imprniou~ surfaces. ivhereas 27% of ered by paving the front or other yard area and 21% of the back yard area is c’ovstructures. The limited capacity of side yard 119 greenspace to se,asonally wet handle the basements drained soils in the sufficient greenspace Creenjpace runoff residential to absorb charwtertstic> 01’ I’ront. among lawn hledian vegetable Ilower other cover tree numbers Stde - well- yards have back Back 1 ards Range .7_.> _ _ 1 Ij- 1 2 1 z-5; S-66 6-“1 garden garden area t ret: cenop> ;Irc;r ol’ 1 drds wtth lawn, Mtth shrubs 4-20 66-9; 16-65 11-3” u ith gardens other ),ards hlrdian Range hlcdian 14 I2 19 53-65 4 l-65 2-Y-4& 62 62 40 :jt?-lir@ 43--ci; 2;-$2 Qb 58 66 :j--26 j- L 7 !j bare soil I’rom trampling o-11 - bare soil irom trees 9-15 - cultivated - u ild groundcover groundcover 5-33 8-24 b-55 trees Predominant 4 20 1; 11 12 ;8 40 .,__.-I COLCI - w.ith for deep, area active with \ ards 11-22 1.3-29 acttve Percent is responsible J ards 1 jhru b tirea - paving predominantly yards dre;i area garden and despite .tdt;. and hack Range alI greenspace roofs areas. Generally, only the most of their water load. Front Dtjtribution from in Syracuse. iunrtion 9 4 lk 15 16 5-39 S-50 l-l 12 24 21 55-90 72 26 44 1” 14 0 5-56 w-5 o-23 ‘l-60 O-28 34 3 I0 41 1 40 5; 5 38 46 15 7 S6 33 “S-53 36-6-l O-23 11-36 35-_;5 6-30 o-31 6-90 IO-81 35 5ti 6 31 60 14 5 49 -14 oi shrubs in )‘;irds hedge 4-45 “3-73 r,-v3 foundation hedge and iou ndat ton specimen human food Care i& b-3 01’ vegeration in )‘ards IAN ns showing tntensc lawns casual showing neglected care care lawns shrubs showing intensILe shrubs showing casual H ild or neglected care shrubs trees showing intensive trees casual wild showing or neglected care care care trees 23-s-1 26-6s O-19 12--51 25- ; 3 o-3d tj-‘>:j S6-IO0 O-63 120 We also recorded of yards the presence to indicate and type its use for enclosure of fencing along or screening. the boundaries In most tracts, over 90% of the front yards, over 8057 of side yards and over half of the back yards are not fenced (Table VI). Conversely, less than half of the back yards, people and few front or side yards, have wire fences sufficient to restrict or dogs. The few wooden screens and rustic fences also are most I> in back yards. No clear differences the census tracts. We were interested in the use of fencing in the distribution, care and are indicated function among of vegetation types in front, side and back yards as indications of the revealed preferences of residents toward their greenspace. and also resident orientations toward the neighborhood, adjacent neighbors and their more personal interests. This may be most valid for one-family, owner-occupied homes. as are predominant in this study: the attitudes differ from the preferences of residences in of the care of greenspace with the care of owner-occupied and rented residences to buildings versus yards. but this cannot be spect, resident tenure should have been of property managers ma> rented units. Comparisons residences may be valid for both identify the priorities given to tested from our data. In retrorecorded when permission for access to lots was obtained. To compare the care of residences and greenspace, we equated houses needing minor repairs wlth casual care of vegetation as the generAy expected norms in Syracuse. More and less intensive care of both could be consistently the comparisons are meaningful. We also attempted to distinguish distirquished. wild from SO we believe neglected vegetation, that be- cause shrubs and trees m particular can be left unattended for several yeara in locations suitable for wildlife habitat, screening. and other values. Llnattended vegetation M’~S judged wild unless uncorrected damage or other However. it is difficult to discern resident problems suggested neglect. motives for leaving vegetation unattended. and our criteria for wild versus neglected vegetation were not sufficient to accomplish this. Direct inter. viekvs with residents would be desirable to refine this distinction. because conflicting attitudes toward wild vegetation ‘are apparent among city residents. In most study tracts, lawns are nearly universal III front and back yards. and only a little less common In the smaller side yard5 ITable median distribution of la\ix area closely matches the distribution VIII. The of green- space ruea among the three yards. Compared with the care of residence<. lawns generally show fairly good care. and there is only a moderate decline in care from front to back yards. There is no clear pattern for intensive care of lawn5 among in all tracts. However. tracts: mo<t this is a personal choice of many neglected lawns are in tracts with housing in poor repair. In all tracts, more front yards have shrubs and the proportlon of shrub area to greenspacr residrnts the most than cto sictr or back yards. area is ‘also highest in front 121 yards. Most shrubs receive intensive care care in side and back yards. The relatively worthy in light of much of Lawn care. Identifying in front yards, and more casual intensive care of shrubs is note- less commercial promotion of shrub shrub areas in Jrards by their primary care than function. foundation shrubs predominate in front yards and are also common in side yards, but are not common along the backs of houses. Hedge and foun. dation shrubs are used together to encircle more front yards. but hedge shrubs alone are most comtnon in back yards. Specimen or flowermg shrubs are most common in back yards. where we also recorded most shrubs for human food - primarily grapes and brambles. Rubus sp. The occurrence of food shrubs is probably underestimated because small areas of these occaslonall~p M’ere included with other shrubs. The relatively lo\\, proportion of shrub area in relation to available grernspace in back yrvds is unfortunate for urb~l wildlife. eq~eciall> songbirds. for which shrub cover IS partrcularl>~ valuable I DeGraaf and Thomas. 19761. Interconnecting bat:k y,ards through the centers of blocks offer the greatest potential for habitat corridors is most residential areas. .A survey of altitudes toward ~\.ildhfe in several urban areas of Neil, I’ork reported that Syracuse respondents espressed above-average Interest III encoutxglng backyard or neighborhood wildlife with respondents from other cities. !BroM.n and Dawjon. 19751. But along they pave more attention to bird feeders. houses. and w’ater structures than to wildlife plants. As would be expected. the occurrence of gardens able than that or side yards. of flower-garden or but are present garclrtw occupy of the \,egetable of laa.ns slightly garden area shrubs. in most Gardens are back yards. in yards absent In most from is more most varifront trac’ts. vegetable greater total area than do flower gardens. hlost &area is U-I hack yards. but the median proportion to greenspace area 1~ greater III side and front !V~cl~. This suggests that flower gardening is oriented more to the neighborhood ruid neighbors. w.hile vegetable gardening either 15 more prwate or slmpl> reflects the greater space available In bat.-k yards. Gardens also r;aq’ more over time than do Iawns and shrubs. \\‘e distinguished active from inactive prdens to get a partial Indication of change over time: rec:entl>p added gardens c:ouid not be identified. .A median of usually from the prt’. 35 of back>pard vegetable garclens are abandoned. VIOLIS year. Tll~ suggests a small annual variation in this activity in most tracts. I\lnny perennihl flowers can persist for several ).ears after abandonment. so these indrcate decline in gardening interest over a longer period. hleclians of 11’; of the flo\f.er garden area in front and slcle yarcl~. and l-15 in ba(:k yarcl~. rue inactive. The highest proportions of Inactive flower gardens &are in tracts that have undergone substantial change from o\\.nerowuparic~~ to renters in the last decade. Other cover generally occupies a smaller proportIon of front yards. ancl more of back yards. in t-elation to greenspace areas. Cultivated grounclcover. especially \‘rnca. Pa~h.w7ndra. and Hedera sp.. is the most common type in front vated species yards. but in side and wild groundcover back yards. Wild is nearly as common groundcover, mostly as cultiperennial forb species. map indicate either casualness or neglect of these areas. Bare soil from trampling is minor in comparison with lawn area, but increases from front to back yards as a reflection of more casual lawn care. The area of bare soil from tree shade is proportional to tree but averages only about 10% of the tree ca~~opy area. Trees are absent yards in nine tracts. Median from most front yards in seven tracts, tracts, but are present in the distribution of tree canopy cover and in yards. most side majority of back yards in all area is roughly proportional to greenspace area among yards. but tree numbers are proportionally greater 111 back yards because of more small trees there. Casual care of trees predominates, and a much lower proportion of trees have received intensive care than have shrubs or lawns. The relatively high proportions of wild or neglected trees in side and back yards suggests that many of these trees have been left deliberately for screening between houses and lots. On many older lots, thesta trees have overgrown and replaced shrub hedges. However. it appears that most of the wild or neglected trees are removed when they interfere with other yard values: would have accumulated in these yards. The yards. study clearly Treatment of indicate?; frontyard entation to the neighborhood. mixed; there IS relatively heavy otherwise differences vegetation greater in resident generally tree canopy orientation area among suggests a strong ori- Orientation to adjacent neighbors is more use of flowers in side yards. but also more use of heclge shrubs and wild or neglected Back yards appear to be more personally trees that may serve as screens. oriented to the residents. and they generally receive more casual care. The changes from open to closed residential landscapes over time. dlscussed by Schmid 119751. do not apply as \vell to Syracuse. blast front yards are quite open in all study tracts. Most back yards are closed b> fences. hedge shrubs. or tree screens. and average only slightly more open in the newer than tn the older tract>. Open and closed landscapes In the residential areas of Syracuse are interspersed. rather than being related vev clexl)’ tcJ devek>pnlent &a&g?. Because front yards strongly relate to and impact on the streetsides and neighborhood. it is useful to consider frontyard and public streetside space and vegetation together as the <treetfront resource. \‘lewed from aerial photos. residential areas in Syracuse generally shop. prominent strips of greenspace and trees running through back yards and smaller strips along street fronts I Fig. 3’1. Comparing the two resource areas. back yards and street fronts. our study finds a range runong tract means of 1.5 to 2.-l times more backy,ud than streetfront greensparr. and 0.9 to 1.8 times more backyard tree canopy &area. Therefore. III most tracts. proportionally greater tree canopy is supported to greater stresses on streetfront by the streetfront space. This contributes trees that must be reflectrcl III their joint. 123 the more public-private management. Conversely, of backyard trees appears justified in this respect. Our findings of different physical character and casual implied management social orienta- tion of front, side and back yards in Syracuse invites speculation on the probable effects of other types of residential layout not common in this city. Positioning of houses close to the public streetside reduces the potential use of frontyard vegetation and places more emphasis on building fronts. Perhaps more important is the reduced streetfront space for support of public street trees. Reduction of side yards by semi-attached or because of the more limited sideyard row housing may have less effect, space to be lost. and also the ambivalent orientation toward adjacent neighbors. However, if this housing pattern is associated with narrower lots. impacts between neighbors may be intensified in back yards. In many recent developments using cluster housing, back yards have been reduced in favor of more public or communal greenspace area. If closure of the back yards is not developed or permitted, they may serve Also, the practice in some new deless personal functions for residents. velopments of separating sidewalks from streets. and locating them instead in public or communal space behind houses. reduces the distinction between public and personal parison with the character rtises interesting questions orientations of front and back and use of residential greenspace as to how these new developments yards. Com- 111 Syracuse will reflect residential heterogeneity over time. Syracuse is a moderatedensitJ’ city with apparently adequate and useful resident ial greenspace resources. at least In Its predominantly residential at the 1980 population densit), areas. It is also reasonably space-efficient: of Syracuse. the current population of the United States would occup less than 15 of the nation’s land area. It would be informative to have comparable studies of residential greenspnce and vegetation character in communities reflecting alternative approaches to efficient use of residential space. The fmdings of this study do noI hypothesis: that changing development to share similar social characteristics in residential grernspace character city. Rather, this study documents space and vegetation in Syracuse. from 30 to 100 years old - ample among lots, even where they may However. because of the rather provlcle strong support of our Initial patterns and tendencies of residents should result In fewer differences within great areas than heterogeneity among are&as of of residential the green- hlost residential areas of this city range time for espresslon of much individualit! have been more homogeneous origInally. \veak relationshIps of most lot compo- nents to features mdentifiable by tracts in Syracuse. 1l.e believe that our detajlecl analysis of 187 lots in ten selected census tracts provides an ade- quate basis for ch,aracterizing residential greenspace and vegetation throughout this city. Provision for more residential greenspace by developing large1 lots in portions of Syracuse ~w~marily has resulted features of residential vegetation are dependent than available space. in more lawn area. Other mostly on factors other This study gives credence to our hypothesis that physical evidence of the treatment of residential greenspace and vegetation. as compared with other features withln lots. indicates residents’ revealed preferences toward these resources. However. motwes cannot be determined wholly from @ysical evidence. and it 1s difficult to separate Inertia from current values. Distinction between otvner-occupied and rented residences would have been useful in this study to refine yards espress different orientations the concept of residents that front. side. and back toward the neighborhoods. adjacent neighbors, and more k’ersonal interests. This case study describes greenspace and vegetation in a resldentlal pattern common in many urban communities of the same development period in the Clnited States - detached. mostly single-family houses but also twoor more-unit residences. positioned on generally rectangular lots so as to provide front. side and back yards. Comparable studies in other communities and residential patterns are needed to esamine the effects of regional differences and alternative approaches to use of residential space on the chraracter ,and use of residential greenspace and vegetation. We recommend our gener,aJ methodolom modifications to recluce fieldwork for such studies. but suggest some and to refine information. We believe that. for any consideration of residential greenspace and vegetation. at least some data at about the level of detail used in this study 13 needed to qualify more readily available generalizecl information on these compies resources. This study was partially supl.‘orted by funding from the C:onsortwm for Environmental Forestry Studieb. L1SD.A Forest Service. Valuable advice on manuscript development was provided by R.A. Rowntree and R.A. Sanders. Northeastern Forest Esperiment Station. USDA Forest Service. Lanler. C N.. Proc. Dtvtsion Last, 19b:! Dutch Elm oi F T.. Natural Good. Its stock oi Behariol.,modifytng chemicals Disease -1-7 Sympostttm. Resources. J.E.C.. trees. Wtnnipeg. Watson. R.H. a continutng Man.. and amenity Dutch 1951. In October pp. Crleg, and elm dtrease IVtnnlpeg. control. hItin. In hlanltoba 3;1--39.1. . 1976. The D A timber resource city Scott. oi Edinburgh For. - 11% 30 126 hlallette. J R.. 1932. hlensurational Science oi Enwronmental 70 pp. hlarotz. data C.A and Richards. 197.5. Nebv Sork. 1975. Department Slmpsun. and Syracuse, d A., R.-J.. Bur Syracuw. 611 pp. State Census. ShlS.4. urban trees. hl S Thesis. College of New York. $racuse. NY. snd characterization . 12 hleteorol oisuriace material 919-923 trees in Syracuse State Ltnnewty - oi 7.3 pp vegetatton - 197il PHCt a review Unlversttl oi urban photovaphy. l[niversit>’ 1571 J. Appl. oi ltntversit>, J C.. 1X9 Streetside space and Street oi En\trr~nmental Science and Fore+ty. Inirstigation aerial State Acquisition studies. of Geography. 1681 N l’. NY. Llrban color.infrared and Forestry. 1I.S . 1973 J C climatological N .A. and Stevens. hltsc Pub1 . College Schmld. 161. Coiner. for urban charactertzatton and Forestry. residenti hl S Thesis. of New York. Census uf 1 ,.309. ;Ind oi Chicago. I! S. Syracuse. populatlun Department Chicago IL. 266 greenspace Collepr? stud? Res Pap uith lerge.scale Envtronmental color Science 61 pp. NS. and of of case pp housing. Commerce. census tracts Washington. DC.