Enlightened Self-Interest: How the National Economy, Ideology, and

Anti-Americanism Influence Public Opinion on Foreign Investment

AR~cHNES

By Joyce Lawrence

Master of Pacific International Affairs

University of California, San Diego, 2008

B.S. in Business Administration

Washington University in St. Louis, 2004

OF TECHNOLOGY

AY j 2014

V3 R A

IILc)

Submitted to the MIT Department of Political Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the

Degree of

Master of Science in Political Science

At the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

February 2014

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All Rights Reserved.

Signature of Author .....

.......................................

_"tV---------// ----

MIT Political Science Department

February 7, 2014

Certified by .........................

......................................................

Ben Ross Schneider

Ford International Professor of Political Science

Thesis Supervisor

Accepted by .................................................

Roger Petersen

Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science

Graduate Program Committee Chair

Enlightened Self-Interest: How the National Economy, Ideology, and

Anti-Americanism Influence Public Opinion on Foreign Investment

By Joyce Lawrence

Submitted to the Department of Political Science

On February 7, 2014 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Science in Political Science

Abstract

Despite the benefits of economic globalization, popular opposition to foreign investment continues to

influence policy debates. What explains opposition to foreign investment? Standard political economy

theories suggest that support for international trade, immigration, and investment all depend on the

impact these policies have on potential earnings in the labor market. According to standard models, those

who stand to benefit economically from international exchange are expected to be more supportive than

those who will face increased competition and declining wages. An analysis of four cross-national surveys

from 57 countries provides empirical evidence that public opinion on foreign investment is not

determined by economic self-interest, but rather by evaluations of the national economy, political

ideology, and attitudes about the United States. These findings have implications for understanding the

debate over globalization policy and domestic support for further liberalization around the world.

Thesis Advisor: Ben Ross Schneider, Ford International Professor of Political Science

2

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................

4

II.

Foreign Direct Investm ent in Developing Countries .......................................................................

9

Ill.

Public Opinion and Econom ic Policy Issues ..............................................................................

13

IV.

Literature Review : Public Opinion and FDI................................................................................

15

V.

Theory and Hypotheses......................................................................................................................23

VI.

Research M ethodology...................................................................................................................29

VII.

National Economic Evaluations and Support for FDI in Latin America ....................................

33

Baseline M odel: Education and Skills.................................................................................................

41

Economic Perceptions: Egocentric and Sociotropic Models of FDI Preferences ...............................

45

Nationalism, Ideology, and Country of Origin ...................................................................................

48

VIII.

Anti-Am erican Sentim ent and Attitudes on FDI........................................................................

Baseline M odel .......................................................................................................................................

52

54

Nationalism and Anti-Am erican Sentim ent...........................................................................................57

IX.

Conclusion.......................................................................................................................................61

References ..................................................................................................................................................

3

64

I.

Introduction

The growth in international flows of trade and capital in recent decades created substantial

economic growth, lifting millions out of poverty and raising the standard of living around the world. In

2011, global foreign investment inflows totaled $1.5 trillion, more than the entire economic output of

Mexico. Free movement of investment capital creates economic efficiencies by allowing investors to go

where returns are highest, and direct investment means multinational corporations (MNCs) can reach

new markets while retaining control over their operations. The host countries that receive foreign

direct investment (FDI) can experience job growth, access to new technology, and increased tax

revenues (Lipsey, 2004), but the benefits of spillovers from FDI depend on the capacity of the host

economy to absorb new skills and technology (Crespo & Fontoura, 2007). Policy barriers to foreign

investment have dropped significantly in recent years, but developing countries continue to have more

restrictions on foreign investment than developed countries (Golub, 2009). Despite a broad trend

toward the liberalization of cross-border investment, opponents of globalization continue to be a strong

political force (Rodrik, 1997; Stiglitz, 2002), and the debate about the benefits of FDI to host countries

remains an active one.1

This paper will contribute to a better understanding of how economic calculations and cultural

attitudes influence domestic support for foreign investment using cross-national analysis of public

opinion surveys. The question-What accounts for public opinion on foreign investment?-is closely

related to research on other topics in international political economy including international trade and

immigration, which benefit from a large body of research examining both economic and cultural

influences on policy preferences. However, there is relatively little research on foreign investment that

explores domestic policy preferences.

For more on the costs and benefits of FDI to host countries, see Alfaro & Charlton (2007).

4

Recent studies of the politics of foreign investment have developed a political economy model

based on the Heckscher-Ohlin model in international trade, which claims attitudes about foreign

investment are determined by the impact of FDI on labor market outcomes (Pandya, 2010, 2013; Pinto

& Pinto, 2008; Pinto, 2013). According to the factor model, individuals who are most likely to benefit

economically from increased investment (through higher wages and new employment opportunities)

will support greater openness while those whose occupations are likely to face increased competition

will oppose inward investment. In order to identify the beneficiaries of FDI, the authors rely on a simple

two-factor model of production, which assumes labor and capital are the inputs into the production

process. Countries with abundant capital should receive more capital-intensive FDI and places with

abundant labor should receive more labor-intensive FDI, according to this model. This fits the trend

over the last thirty years of industrialized economies outsourcing labor-intensive tasks like electronics

assembly and apparel manufacturing to developing countries like China and Mexico, where labor costs

are lower. The factor model is used by both Pinto and Pandya as the theoretical foundation for

explaining cross-country differences in FDI policy. The factor model is now a standard approach in

studies of the politics of FDI. However, a deeper investigation of public opinion reveals that the factor

model is flawed because it does not take into account the limitations of public opinion and reasoning on

complex economic policy issues.

In contrast to the factor model, which focuses on economic self-interest as the primary factor in

attitudes about FDI, my analysis demonstrates that public opinion about foreign investment depends on

evaluations of the broader state of the national economy and ideas about the sending country. Based

on an analysis of public opinion surveys conducted across 17 Latin American countries on political and

economic issues, I find that opposition to FDI is strongest among those who believe the national

economy is in decline regardless of their own income. A study of attitudes about FDI based on a

different sample of 57 countries shows that anti-American attitudes are a significant predictor of

5

opposition to FDI. These findings refute the existing political economy theory and offer evidence that

supports an alternative theory of public opinion that is driven by heuristics rather than economic selfinterest calculations. Distinguishing between the two models is important because they lead to

different implications for who will support increased liberalization of foreign investment in developing

countries.

Early empirical research on the politics of globalization found some support for the link between

labor market outcomes and attitudes about globalization in developed countries, but also produced a

puzzle about responses in developing countries. Survey analysis of trade policy preferences in the

United States shows that those with higher skills, as measured by education, tend to support increased

international trade (Scheve & Slaughter, 2001). While there is a significant relationship between skills

and positions on globalization, this factor explains relatively little of the overall variation. Furthermore,

the theory no longer holds when developing countries are included in the analysis. Extending the labor

market theory to developing countries implies that lower-skilled individuals in these places should be

more accepting of globalization because competitive advantage dictates that they are the primary

beneficiaries. However, the correlation between education and attitudes about globalization holds even

in developing countries in which lower-skilled individuals are the ones who stand to benefit the most

from openness to trade (Beaulieu, Yatawara, & Wang, 2005). The analysis that follows will show that

the same relationship holds true for foreign investment. Low-skilled workers in developing countries,

who stand to gain the most from FDI according to factor models, are less supportive of it than highskilled workers.

This finding is puzzling because it is the opposite of what one would predict based on the

standard Heckscher-Ohlin model. Although the Heckscher-Ohlin model was developed as a

macroeconomic model to predict aggregate trade flows, it has clear political implications for which

groups will benefit most from international trade. Stolper and Samuelson (1941) extends the theory to

6

politics by arguing that those who benefit most from trade will support it and those who are harmed by

trade will oppose it. This insight forms the basis of political economy studies of both trade policy and

FDI such as the recent work by Pandya and Pinto. The growth in surveys that address political issues like

2

trade, immigration, and foreign investment since the 1990s has made it possible to test the Stolper-

Samuelson predictions at the individual level, contributing to a growing body of research on public

opinion and globalization.

This research paper finds evidence that contradicts the political economy model of FDI

preferences. It advances the debate about the "education puzzle" in globalization research by showing

that the factor model is not sufficient to explain policy preferences on foreign investment. Adopting

some of the insights of earlier work on trade and immigration, this analysis shows that education is

linked to attitudes about foreign investment, not through labor market outcomes, but because

education is associated with economic knowledge and cosmopolitan belief systems. By using multiple

surveys and a broad selection of countries, this data increases the generalizability of the findings and

expands the scope of previous analyses to new countries.

The empirical analysis uses multiple cross-national surveys to test hypotheses about the

determinants of preferences on foreign investment. The Latinobarometer surveys from 1995, 1998, and

2001 all include questions about FDI and national economic perceptions, so they are an ideal source for

studying how evaluations of the economy relate to foreign investment policy preferences. These

surveys include data from 17 Latin American countries. The analysis of pro/anti-American sentiment

comes from the 2006 Gallup Voice of the People Survey, which was conducted across 57 countries. As

an additional contribution to the field, this research represents the first analysis of the Voice of the

People data to examine public opinion on foreign investment. It is the most comprehensive study to

research on attitudes about international trade and globalization began in the 1970s primarily in

developed countries. For more on the history of survey research, see Groves (2011).

2Survey

7

date on public opinion about foreign investment in developing countries. The data demonstrate a

strong empirical relationship between anti-Americanism and opposition to globalization in many,

although not all, countries. This relationship diminishes the role of education and skills in explaining

attitudes about globalization, even though those with more education remain supportive of

globalization on average even when accounting for anti-American attitudes. The analysis also indicates

the weaknesses in the standard factor model and the importance of cultural influences in better

explaining the variation in preferences.

This research provides an original contribution to the study of public opinion on globalization by

examining new data and new hypotheses about foreign investment policy. Beyond the original

academic contributions of this work, this paper also provides practical implications for foreign investors

and policymakers. When foreign investment deals go awry, there can be large costs for the firms

involved. Both investors and politicians want to know why investments are likely to face public

resistance to avoid political risks and respond to public opinion. If existing theories of public opinion and

FDI policy are incomplete or incorrect, then the solutions they imply for generating support for FDI will

be ineffective. While this analysis is not intended to predict support or opposition to any particular

investment or policy change, it shows that national economic conditions and beliefs about the sending

country can influence support for foreign investment in general. These relationships are surprising in

light of existing models, but may seem intuitive for those familiar with foreign investment and political

risk. Savvy investors and politicians may take these factors into account already, but this work

demonstrates the power of these explanations relative to the existing political economy model. This

research improves on existing theories of foreign investment preferences and provides an important

corrective to the standard factor model while exploring opposition to globalization in a broader sample

of developing countries.

8

II.

Foreign Direct Investment in Developing Countries

Foreign investors are increasingly directing funds to developing economies, yet these

investments remain politically controversial. Political debates concern both the economic impact of

investment, who benefits and who is harmed by open investment policies, and cultural and nationalistic

ideas about who should own industries and resources within the economy. Existing theories of FDI

preferences are insufficient to explain the wide variation in opinions about FDI around the world. After

defining FDI and describing how it has changed over time, I outline the debate about its economic

effects and the policies that governments in developing countries have adopted to encourage or

discourage foreign investment. This overview of foreign investment provides the motivation and

context for studying public opinion and foreign investment.

The technical definition of FDI is foreign investment with an ownership stake of at least 10

percent 3 , but this definition masks large differences in the types of foreign investment. Multinational

companies (MNCs) have multiple and diverse motives for investing, including access to new markets,

cheap labor, and natural resources. Fundamentally, the strategic decision about whether a firm should

invest directly, export, or enter a licensing agreement depends on the firm-specific advantages of

internalizing the production process (Dunning, 1974). Only when a firm benefits from controlling the

production of goods and services within the firm's own boundaries is FDI the optimal strategic choice for

international expansion. While each firm makes investment decisions based on its own calculation of

the costs and benefits of investing abroad, the location of FDI also depends on characteristics of the host

country. Although any given investment may favor skilled or unskilled labor, both economic theory and

empirical evidence confirm that at an aggregate level, FDI reflects the comparative advantage of the

host country (Qiu, 2003). In countries where labor is abundant, FDI more often flows to labor-intensive

is the definition currently used by the IMF, which is standard in analyses of FDI. The 10 percent cutoff is

arbitrary, but allows for comparability across data sources.

3This

9

industries like manufacturing, whereas in developed economies FDI is more likely to target capitalintensive service sectors. Much like international trade flows, FDI flows follow the patterns of

comparative advantage at the macroeconomic level despite heterogeneity among firms.

FDI refers to the ownership of assets in a host country, but there are many different forms FDI

can take, and these may have different implications for public support of FDI. FDI can be categorized as

greenfield investment, which involves creating a new business, a merger or acquisition of an existing

company, a joint venture with a domestic firm, or reinvesting additional capital into an existing foreignowned firm. A new greenfield investment is often the most desirable form of FDI because it directly

creates new jobs. Governments are increasingly competing to attract multinational companies (MNCs)

to invest in greenfield operations using tax incentives and subsidies (Blomstr6m, Kokko, & Mucchielli,

2003; Easson, 2001; Parys & James, 2010). Other forms of FDI may have a different impact on the local

economy. In some cases, a foreign acquisition of a domestic firm will result in job losses as the foreign

owner consolidates operations. FDI is a multi-faceted concept, and even economists debate whether it

has a net positive or negative impact on the host country. It is important to keep in mind that the public

perception of FDI does not necessarily align with the economic reality, and studying opinions about FDI

is useful to uncover both economic and non-economic reasons for FDI preferences.

FDI typically entails a longer term investment than portfolio flows, making it a more stable form

of international capital. This stability of FDI flows is one of the reasons that governments in developing

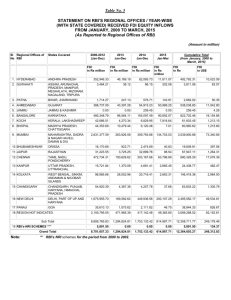

countries are increasingly seeking out FDI and reducing the barriers to investment. As shown in Figure

1, firms invested over $1.5 trillion abroad in 2011, a 25 percent increase over the last decade.4 The

following year, for the first time in history, investment flows to developing countries were larger than

those to developed economies, a trend which marks an important shift in the global economy.

4 (UNCTAD, 2012)

10

Understanding attitudes about FDI in developing countries is more important than ever before given the

growth in foreign investment flows.

FDI Inflows to Developing Economies

800

700

600

$

500

400

300

200

100

-

0

Q

r-

N~ I;

r- r-

W~

00

0

N~

:T

W

00

00

C)

0)

N_

M~

--:

M

W

0)

00

a)

r- r- 00 00 00 00

o)

a) 0) 0) 0) 0) a) Mn a)a

o-) 0) a) oCn a)

1

.- 1

- 1

r1 1-H

1--1 ~--1

11

1.H

.

r Africa

U Latin America

C

D

0

N

N

CD

0D

(N

-t LO

CD 0

0D CD

N~ N1

00

0

0D

N

CD

-1

0

N

U Asia

Figure 1: FDI Inflows to Developing Economies

In recent years, governments have sought to attract FDI as a tool for economic development

because of its potential for new jobs, technology transfer, and skill development. However, the benefits

of FDI remain controversial. Foreign firms are often subject to criticism for not investing in local workers

or using local suppliers (Georgiou & Weinhold, 1992). Increasing competition to attract foreign

investment means more governments are offering tax benefits to investors. Although tax incentives are

an effective device for politicians to claim credit for economic development (Jensen et al., 2010), the

benefits realized from FDI often fail to compensate for the tax and subsidy packages that investors

receive (Blomstrom et al. 2003).

Politicians frequently use anti-foreign investment messages to mobilize groups that oppose

globalization. These efforts have led to the nationalization of foreign investments and the expropriation

of foreign-owned assets in some countries. In Latin America, populists in Venezuela and Argentina have

recently nationalized industries or broken contracts with foreign investors in favor of domestic

ownership of industry. The Bolivian president Evo Morales is an outspoken critic of the role of multinational corporations (MNCs) in Latin America and has nationalized 14 companies since taking office in

11

2006. In a 2012 speech, he stated, "Sovereignty over natural resources is a requirement for liberation

from colonial and neoliberal domination and for the full development of the people ... However, in

most countries this wealth has been looted and appropriated in private hands and by transnational

powers that enrich themselves at the expense of the people." This statement epitomizes the populist

opposition to FDI that continues to play an important role in the politics of many developing countries.

The government of India recently scaled back plans to open the retail sector to foreign competition after

a public outcry in support of small local shopkeepers. Clearly, domestic political concerns reveal mixed

feelings about the value of FDL. A better understanding of constituent perceptions and preferences can

help leaders balance the interest of voters, businesses, and foreign partners when determining policy.

12

lil.

Public Opinion and Economic Policy Issues

Political scientists have been studying public opinion since the first surveys using population

sampling were introduced in the 1940s. Research on public opinion has generated many insights about

political attitudes, preferences, and behavior, and it is important to consider how the developments in

survey research relate to the study of economic policy preferences. One of the results from early public

opinion research in the United States is that citizens are not well-informed about public policy

(Schattschneider, 1975). This result implies that survey responses should not be viewed as informed

beliefs based on a rational calculation of the economic consequences of a policy, as they often are in

strict rational choice models. Instead, public opinion represents positive or negative sentiment about an

issue that is not necessarily a deeply held belief, but instead may be informed by cues like elite opinion

(Berinsky, 2009), ideology (Dalton, 2008), and reasoning based on heuristics (Mondak, 1993). Moreover,

individual opinions need not be rational in order to generate policies that reflect aggregate opinions in

an economically rational way (Erikson, Wright, & McIver, 1993; Page & Shapiro, 2010). The weight of

evidence from survey analysis in the United States is that economic self-interest is insufficient to

understand individual policy preferences, but this remains the standard model in studies of the politics

of foreign investment,

The lack of policy knowledge in the general population is one factor to consider for any public

opinion research. Although the surveys I examine do not assess respondents' knowledge of economics

or economic policy, research on other policy issues indicates that citizens are often misinformed or

uninformed about economic policy issues (Carpini, 1996). If citizens do not know the definition of

foreign direct investment or how it works, then why study public preferences on FDI? What does it

mean to study public opinion about an issue that few people fully understand? I argue that complete

information and knowledge of a topic is not necessary to form an opinion about a policy issue. Even for

highly salient economic issues like unemployment, the public is often misinformed about technical

13

definitions and subject to the influence of anchoring values (Ansolabehere, Meredith, & Snowberg,

2013). Despite this lack of knowledge, few would argue that attitudes about unemployment are not

meaningful. In the same way, the public does not need to know exactly how much FDI is flowing into

the country or the definition of greenfield investment in order to have a positive or negative attitude

about foreign investment. Respondents understand the meaning of the words "foreign" and

"investment" and have impressions and associations that inform their attitudes about foreign

investment and their responses to survey questions on the topic. Politicians respond to voters who have

limited information, so even uninformed opinions are important because they have the potential to

influence policies.

Much like other economic policies, foreign investment can become a flashpoint when an

investment is controversial or a new international agreement is signed, but it has low salience most of

the time. It is not necessary that individuals have deeply held beliefs about foreign investment or pay

attention to it all the time. As with any other policy issue, attention spikes and then subsides. It is often

a minor issue during election time unless there is a specific triggering event that generates news

coverage. Yet, understanding the determinants of public opinion can be especially important when it

becomes a major political issue, and there is a gap between the latest research on public opinion and

the assumptions of political economy models of FDI preferences.

14

IV.

Literature Review: Public Opinion and FDI

Research on the politics of FDI is a growing field in international political economy, but there are

still only a few studies that focus specifically on FDI preferences and policy toward inward foreign

investment. However, the more mature research on trade and immigration offers many useful insights

that may apply to FDI. In particular, studies indicate that national economic conditions and cultural

attitudes matter for support of foreign economic policies. Despite this evidence, most research on FDI

focuses primarily on individual economic self-interest as the driver of both preferences on FDI and

national policies. This limited focus overlooks important insights from the broader field of foreign

economic policy preferences, specifically recent contributions from the fields of trade and immigration

that can be adapted to the study of FDI.

When individual actors are considered in research on the politics of FDI, the focus is most often

on the perspective of investors evaluating political risk in destination countries. Foreign investors face

the risk that governments will change regulations, breach contracts, expropriate assets or otherwise

reduce the value of investments. While this research offers interesting insights about how political

institutions influence risk, it does not address how host governments make policy to restrict or

encourage FDI. Political institutions play an important role in constraining leaders from taking actions

that might harm investors. Research in this area indicates that democracies are better at creating a

credible commitment to property rights, which in turn contributes to higher levels of investment

(Jensen, 2006; Jensen et al., 2012; Li & Resnick, 2003). While better knowledge about how international

firms consider political risk is valuable, it is only one side of the equation. Governments also make

decisions about whether to block or encourage foreign investment within their borders.

Recently, scholars have begun to examine the politics of foreign investment from the "demand

side," analyzing how citizens and governments in host countries attempt to either limit or attract foreign

investors. This new line of inquiry has made substantial progress toward an understanding of FDI policy

15

in host countries, but important gaps remain. Specifically, research has not considered how national

economic conditions influence public support for FDI, or how non-economic factors like nationalism

affect FDI preferences.

Research on the demand for FDI has begun to use the lens of political economy to examine

public preferences toward foreign investment. The prevailing argument in many studies is that those

who benefit most from FDI will tend to favor it while those likely to lose economically from greater

foreign investment will oppose it (Biglaiser et al. 2012; Pandya, 2010; Pinto & Pinto, 2008; Pinto, 2013).

These models depend on the Heckscher-Ohlin model of trade, which famously asserts that the most

abundant factors (capital or labor) in an economy will benefit most from increased trade. A country that

is more abundant in capital will export capital-intensive goods and import labor-intensive goods. This

will increase the demand for capital-intensive production in the domestic economy and reduce the

demand for labor-intensive production as firms respond to international comparative advantages based

on the abundance of factors in each location. The reverse holds true in countries where labor is

abundant relative to capital, which is typical of developing economies. The Stolper-Samuelson Theorem

extends this idea into the political sphere by suggesting that those who benefit most from trade should

support policies that encourage it while those that stand to lose out will oppose increased trade. In the

factor model of trade, abundant labor in developing countries means that workers will favor trade while

owners of capital oppose it. The reverse is expected in industrialized countries.

It is important to note that the factor model requires that factors of production are perfectly

mobile across industries. In practice, this means that capital can be directed to another project with no

transaction costs and workers can easily and immediately transfer their skills to another industry. While

this is a reasonable assumption in some circumstances, factor mobility can change over time and may

differ across countries (Hiscox, 1999). Instead, the specific factors model, known as the Ricardo-Viner

model, may better reflect individual incentives. The Ricardo-Viner model posits that the losers from

16

globalization will be those who work in import-competing industries, regardless of their skill level. If the

assumption of factor mobility is wrong, the cleavage on globalization may be industry rather than skill

level. However, empirical research in this area finds little relationship between industry and

globalization preferences (Hays, 2009; Mansfield & Mutz, 2009; Scheve & Slaughter, 2001).

Building on the factor model, scholars studying FDI argue that labor benefits from increased

inflows of FDI because it creates competition and drives up wages, but domestic producers lose out

from the increased competition in both labor and product markets (Pinto & Pinto, 2008; Pinto, 2013).

Studies confirm that foreign investors pay higher wages on average than domestic firms (Conyon et al.,

2002; Feenstra & Hanson, 1995). Therefore, the largest support for FDI should come from workers and

the political parties that depend on votes from labor. Pinto & Pinto (2008) find that right-leaning

governments are more likely to receive FDI in energy and construction industries, which benefit

domestic owners of capital, while left-leaning governments attract more investment in manufacturing

as it drives up competition for labor. The empirical support for the theory relies on data on inflows of

FDI by sector under different partisan governments. While this data captures the ultimate outcome of

investment flows that result from an interaction between investors and politics, it does not analyze the

individual preferences on either side. An analysis at the individual level is a necessary first step to test

the mechanism that foreign investment flows reflect economic self-interest, which leads politicians to

support the FDI policies that their constituents favor. The theory implies that workers will be more

supportive of FDI than business owners, and that their political representatives will favor policies that

attract FDI to labor-intensive sectors. However, it does not directly test this hypothesis at the individual

level.

In one of the few studies that analyzes survey data on FDI preferences, Pandya (2010) shows

that high-skilled workers in Latin America are more supportive of FDI than low-skilled workers, even

when taking into consideration job insecurity, attitudes toward privatization, and level of education.

17

This result is contrary to the standard prediction from a factor model of FDI in which the most abundant

factor in society benefits from FDI. In developing countries, low-skilled labor is the most abundant

factor, so this group should be most supportive of FDI. Yet, this group tends to oppose FDI despite the

predicted benefits. Pandya suggests that economic self-interest is still driving opinions about FDI, but

the factor model is incorrect about who benefits from FDI. Foreign firms tend to hire workers with

above average skill levels, so high-skilled workers may benefit more from FDI, which influences their

opinions. Another study of FDI preferences confirms the same pattern among workers in China, but

specifically tests whether the type of FDI influences opinions. High-skilled workers in China are more

supportive of FDI than less skilled workers even when the investment targets low-skilled workers (Zhu,

2011). These results parallel research on trade policy that shows more educated workers tend to favor

openness to international trade even in developing countries where skilled workers are scarce (Chiang,

Liu, & Wen, 2013; Mayda & Rodrik, 2005). Together these surveys present a puzzle for the factor model

because high-skilled workers are more supportive of trade and foreign investment in the developing

countries that are studied even when their personal income is unlikely to be affected.

Research on public opinion about foreign investment has focused primarily on how personal

economic outcomes affect preferences, but there is a significant body of research on other economic

policies, including trade and immigration, that questions this approach. Early research on trade policy

preferences indicated a relationship between factor endowments and support for openness to

international trade with high-skilled workers in developed countries supporting international trade while

low-skilled workers were more likely to oppose it just as the factor model suggests (Balistreri, 1997;

Kaltenthaler et al., 2004; Mayda, 2008; Scheve & Slaughter, 2001). However, one critique of these

empirical studies based on the factor model of trade preferences is that skill levels are often measured

by years of education, which measures not only skill but also socialization into a more cosmopolitan

value system and better knowledge of economics (Hainmueller & Hiscox, 2006). Conflating these

18

factors meant even though education had a significant effect on trade policy preferences, the model

could not differentiate between theories that emphasize personal economic considerations, values, and

knowledge. By comparing those in the labor force to retirees with similar levels of education,

Hainmueller and Hiscox (2006) found that education continued to influence trade policy preferences

even when trade no longer had an impact on personal income. This finding indicates that individual

economic considerations were overstated in earlier research and that education contributes to support

for trade through other means, including socialization into cosmopolitan values and training in

economics. This important insight has not been incorporated into the study of FDI preferences, which

continue to interpret education as primarily an indicator of an individual's economic opportunities.

The literature on economic voting5 suggests the current focus on how personal economic

conditions influence FDI preferences is misplaced because people often look to the national economy to

evaluate economic policies. This criticism has recently been incorporated into research on trade policy

preferences. The Heckscher-Ohlin model of trade policy preferences places high cognitive requirements

on individuals who must think about the impact of trade policy on their personal economic situation

(Mansfield & Mutz, 2009). This requires a complex calculation of how national policy relates to a local

phenomenon. In the literature on economic voting, there has been a long-running debate about

whether citizens vote based on changes in their own personal economic circumstances, known as the

"pocketbook hypothesis" (Campbell, 1980), or whether they look to the state of the economy more

broadly and vote "sociotropically" (Kinder & Kiewiet, 1981). Recent research on economic voting shows

6

that self-interest rarely drives voting at the national level. Instead, the dominant view today is that

people evaluate political candidates based on the overall health of the economy (Anderson, 2007). This

"sociotropic" theory of voting has influenced research on trade policy preferences. Mansfield and Mutz

s Economic voting is the study of how economic conditions affect vote choice.

6There continues to be some debate about the conditions under which "pocketbook" voting might occur. For an

overview of the research, see Lewis-Beck & Paldam (2000).

19

(2009) find that perceptions of the overall impact of trade on the U.S. economy are the primary

explanation for attitudes toward trade rather than personal economic self-interest. The theory of

"sociotropic" evaluation of economic policy could be applied to foreign investment policy preferences as

well. The varied nature of FDI, which includes greenfield investment, acquisitions, and joint ventures,

means it has even more complex economic implications that make it difficult to determine individual

effects. Yet, no research on FDI has addressed this alternative explanation.

While much of the research on foreign economic policy preferences focuses on economic

explanations, a number of studies address cultural attitudes and values. Globalization has important

economic implications, but international flows of goods, capital and people also have cultural meaning.

The way that people interpret globalization and policies to expand or restrict these flows depends on

cultural beliefs and values. Citizens who are more concerned about preserving national identity should

be the most resistant to foreign influences while those with a more cosmopolitan outlook should be

more supportive of foreign interaction, whether it takes the form of trade, FDI, or immigration. There is

evidence that more cosmopolitan attitudes are associated with greater support for trade (Hainmueller &

Hiscox, 2006; Mansfield & Mutz, 2009) and economic integration (Hooghe & Marks, 2004). Similarly,

studies of attitudes toward immigration indicate that nationalism is a strong predictor of opposition to

immigration, especially among those no longer in the labor force (O'Rourke & Sinnott, 2006). While

these studies mostly rely on observational data, Margalit ( 2012) includes a survey experiment to

demonstrate that perceptions of cultural threat are a causal factor in attitudes about globalization

rather than simply correlated with anti-globalization sentiment. Yet, the only study to examine

nationalism and FDI preferences finds no link between the two (Pandya, 2010). The lack of a

relationship between nationalism and opinions about foreign investment is puzzling considering FDI

raises many of the same concerns as trade policy when it comes to economic reliance on other

countries. The null result may be because of the difficulty in measuring nationalism. There may be

20

some forms of nationalistic beliefs, such as anti-Americanism, that influence opinions about FDI while

national pride or feelings of cultural superiority do not have an effect.

Beyond broad cultural values, preferences toward globalization also reflect specific biases,

prejudices, and opinions about foreign countries and their inhabitants. Several studies show that the

country of origin influences support for FDI (Jensen and Lindstadt, 2012; Jensen and Malesky 2010). In

the US and UK, respondents expressed greater support for investment from Germany compared to

investment from Saudi Arabia. As Jensen and Malesky (2010) suggest, perceptions of national

competitiveness can influence support for foreign investment, which is a possible explanation for

negative reactions to Chinese investment by US respondents in the study. Research on immigration has

also examined country-of-origin effects as they relate to beliefs about immigrants. Immigrants from

different sending countries provoke different reactions and stereotypes (Hainmueller & Hiscox, 2007).

Respondents who believe in negative ethnic stereotypes are more likely to oppose immigration (Burns &

Gimpel, 2000; Citrin et al., 1997). These studies indicate that negative associations with particular

groups are important to understand resistance to certain types of globalization, but the existing

research on how cultural attitudes affect support for FDl does not adequately address the relative

importance of these factors compared to economic explanations.

Research on public opinion about foreign economic policies recognizes there are limitations to

existing surveys. Respondents often have low levels of knowledge about economic policies, and

answers to survey questions depend on how the question is phrased. Recent work in this area examines

how question framing influences public opinion. Hiscox (2006) finds that support for international trade

in the US declines significantly when the question includes negative information about potential job

losses, but it does not increase when there is a positive framing that mentions job gains. When the

survey experiment was repeated in Argentina, the results were similar with the negative framing of the

question producing a stronger effect, especially among those most at risk for job loss (Murillo, Pinto, &

21

Ardanaz, 2012). The order of questions also matters. When questioned about support for both

increased investment opportunities for US investors abroad and greater openness to foreign investment

at home, US respondents were more supportive of FDI when asked first about opportunities for US

investors (Jensen & Lindstadt, 2012). The authors interpret this as a desire for greater reciprocity

because inward FDI is more acceptable when people first consider outward FDI. These studies in

question wording and order make clear that small differences can affect the way that people interpret

questions and which cues they follow. While this indicates that some people do not have strongly held

views on the topic, it does not mean that there is nothing to be gained from survey research. Instead, it

points to the need to study differences across groups on the same question rather than focusing on the

absolute level of support or opposition to FDI.

The literature on preferences toward FDI has focused primarily on the distributional

consequences of foreign investment for individuals and perceptions of the source country, but there are

a number of important explanations of FDI preferences that have been overlooked. There is currently

no satisfactory account of public opinion on foreign investment in developing countries. My research

will explore how the recent developments in theories of trade and immigration preferences apply to

FDI.

22

V.

Theory and Hypotheses

The standard Heckscher-Ohlin factor model that forms the foundation of research on FDI

preferences is simple and intuitive because it relies on rational choices made by individuals pursuing

their economic self-interest. Following the definition in Sears and Funk (1991), self-interest refers to the

short to medium-term impact on the material well-being of the individual's own personal life (or that of

his or her immediate family). If self-interest is not the basis for opinions about FDI, then what are the

alternatives? One alternative is known as "symbolic politics," which refers to learned responses to

political symbols. If attitudes are the result of cultural associations, then economic considerations may

not come into play at all. Another alternative to a theory based on self-interest is that attitudes are the

result of "sociotropic" politics, in which individuals consider the overall impact of a policy on their region

or nation rather than on themselves (Kinder & Kiewiet, 1981). Unlike a theory based on self-interest,

sociotropic theories do not require individuals to calculate the direct impact of a policy on their own

situation. Instead, they simply believe the policy is good for the larger population, which may have

indirect benefits for them personally. This work explores whether self-interest, symbolic politics, or

sociotropic reasoning is best able to account for the empirical pattern of greater support for FDI among

the most skilled and highly educated workers in developing countries. In order to address this question,

I examine the assumptions inherent in the standard economic self-interest theory and offer several

hypotheses that fit with the alternative models.

The factor model relies on economic reasoning about the consequences of FDI, which means

that individuals must understand the economic impact of FDI on their personal economic situation in

order to form an opinion on the issue. There is substantial research on public opinion that questions

whether this is a reasonable assumption. Limited information and uncertainty about policies are

common especially for international economic issues that are removed from the daily experience of

citizens. The immediate and visible impacts of a policy can also sway opinions even if the long-term

23

effects may be different. Ultimately, economic interests are not the only consideration for FDI policies,

which also reflect political ideologies and attitudes about the cultural changes that accompany

international engagement. I propose and test three hypotheses that acknowledge the potential

limitations of reasoning on complex foreign economic policies. The hypotheses are that FDI policy

preferences are informed by national economic conditions, political ideology, and attitudes about major

economic powers. These hypotheses, which are described in more detail below, are designed to

improve existing models of public opinion on FDI. They may be either a complement or a substitute to

the existing factor model, so each hypothesis is evaluated with respect to the baseline model.

One of the most fundamental assumptions of the Heckscher-Ohlin factor model is that the

beneficiaries of globalization are clear a priori and that they can be derived based on the relative levels

of capital and labor in an economy. Instead, I argue that foreign investment has complex consequences

that are not clear at the outset, so it is difficult, if not impossible, for individuals to understand how

investment will affect them personally. While the aggregate impact of foreign investment to developing

countries may be higher wages for low-skilled workers, this outcome is not guaranteed or clear at the

outset. It is hard enough to anticipate the consequences of a particular foreign investment because of

uncertainty about future market outcomes, but foreign investment as a broad category is even more

difficult to evaluate. Even in labor-abundant economies, there are often large foreign investments in

industries that are capital intensive, such as oil and gas extraction, mining, and telecommunications. For

investments in these sectors, the factor model is not expected to hold (Pinto & Pinto, 2008). Given the

uncertainty that surrounds foreign investment and its potential impact, perfectly rational economic

models may not be appropriate because individuals do not form strong views of the expected impact of

FDI on their well-being.

Even if all of the uncertainty surrounding the benefits of foreign investment was removed, the

typical citizen has limited information about foreign investment policy and its relationship to their

24

economic prospects and few reasons to dig deeply into the issue. There is a long tradition in studies of

American public opinion that points to the lack of political knowledge and ideological coherence of

voters (Kinder, 1983). However, more recent research suggests that voters may be able to overcome

the problem of limited information using heuristics, or mental short-cuts, like party labels and expert

opinions (Sniderman, 2000). Studies show that voters frequently use heuristics to make decisions about

candidates when they have little information (Lau & Redlawsk, 2001) and that these may lead to choices

that are rational in the aggregate (Page & Shapiro, 2010). Despite the recognition of voter ignorance

and the use of heuristics by scholars of American public opinion, research on foreign economic policy

preferences ignores these limitations and continues to assume that individuals are well-informed about

complex policy issues.

Standard political economy models assume that all economic benefits are either realized

immediately or discounted appropriately to their present value, but the reality of foreign investment is

that it can take a long time for benefits to materialize and individuals are risk-averse, preferring benefits

now to greater benefits in the future (Holt & Laury, 2002). At the early stages, the costs of new foreign

investment can be more apparent than the long-term benefits. There is a tendency to focus on small

groups that will bear concentrated costs from adjusting to foreign investment rather than on diffuse

benefits because these groups are more organized (Olson, 1965) and often more sympathetic for news

stories. For example, increased competition from foreign retailers has a serious economic impact on

local shop owners, and the closing of local stores makes for a vivid and personal news story that

generates more attention than the long-term benefits of lower prices. Public opinion on FDI is likely to

be shaped by the focus on the immediate negative effects of foreign investment and media coverage

surrounding foreign investment issues.

The standard model emphasizes the economic outcomes of globalization without considering

the importance of cultural changes and identity politics that can influence attitudes. Foreign investment

25

means more than just foreign corporations providing capital for the economy, it means foreign goods

entering the marketplace and foreign ownership of land, resources, and profits. These investments

accompany significant changes to a local economy that can be threatening to those who prefer the

status quo. International exchange brings not only new products and services but new ideas, new

technologies, and new ways of conducting business. For those who hold strong nationalistic values or

negative prejudices about other countries, FDI represents unwanted engagement with other nations.

When it comes to the cultural aspects of globalization, the United States has an outsized presence

because of its influence in the media and entertainment industries, which broadcast American culture

around the world (Margalit, 2012). Yet, these cultural and ideological aspects of foreign investment

preferences are often overlooked.

There are many potential hypotheses that would address the uncertainty about the economic

benefits of FDI, limited information, risk aversion, visibility of groups that are negatively affected, and

feelings of cultural threat. This paper focuses on three areas in particular: evaluations of the national

economy, political ideology, and anti-American sentiment. Each of these addresses some of the

questionable behavioral assumptions in the factor model and allows for a more complete understanding

of preferences on FDI.

While economic explanations of FDI preferences have focused primarily on the distributional

consequences for individuals, there is a tradition of research both in political economy and electoral

studies that shifts the focus to national economic conditions. Based on the insights from this work, I

expect that support for FDI will be greater when the economy is doing well and opposition to FDI will

increase when the economy is perceived to be in decline. For example, studies of violence against

foreign immigrants show that it increases during periods of economic recession because some groups

blame foreigners for the state of the national economy (Alber, 1994). Politicians can also benefit from

blaming foreign corporations for poor economic performance. As Jodice (1980, p. 191) notes, "from the

26

point of view of power maintenance, economic frustrations will be directed against a foreign scapegoatthe multinational enterprise-rather than against the governing regime." Given the incentives of

politicians to use MNCs as scapegoats during periods of economic recession, voters may have more

negative opinions of foreign investment when the economy is in decline. Attitudes about FDI might also

reflect a broader evaluation of economic policy rather than a simple self-interest motivation. Media

coverage about foreign investment is often linked to concern about the decline of the economic

competitiveness rather than highlighting the consequences for particular groups. For these reasons, I

expect support for FDI to be higher among those who believe the economy is doing well and lower

among those who are pessimistic about the economy.

As an economic superpower, the United States is host to many of the largest multi-national

companies that invest abroad and is a major player in international negotiations surrounding foreign

investment and trade policies. Given the substantial role of the United States in foreign economic

policy, it is natural to ask whether anti-American attitudes influence preferences regarding globalization

and foreign investment. There are several mechanisms that could create a link between antiAmericanism and opposition to foreign investment. Positive attitudes about the United States may

indicate a more cosmopolitan and less nationalistic outlook. Those who embrace the United States are

less likely to view investment by a foreign country as coming at the expense of domestic investors or the

national interest. Another possibility is that pro-U.S. attitudes reflect a general agreement with the

principles of US foreign economic policy, which promotes globalization and foreign investment. In this

case, opinions about the United States would fit within a broader ideology of economic liberalism.

Rather than broad ideological agreement, favorable views of the United States may be more specific to

positive feelings about investment by the United States in the country and the benefits of trade and

investment from American companies. Of course, another option is that there is no link between

attitudes about the United States and foreign investment because the two topics are viewed as

27

unrelated. This would be the case if individuals purely consider the economic benefits of policies rather

than their cultural meaning and ideological connotations.

While this theory may appear to give too much weight to the United States in an era when

regionalism is on the rise, it raises important questions about the association between globalization and

American economic dominance that can be tested empirically. If individuals do not link their opinions

about the United States to foreign economic policies, then this will be clear in the data. However,

demonstrating that there is a relationship between anti-American attitudes and opposition to foreign

investment does not differentiate between the various mechanisms that might lead to this result. These

include negative perceptions of American companies that have already invested in the economy,

concerns about the loss of cultural identity through the importation of American products, and

identifying globalization as an American-led ideology. Yet simply testing whether the relationship exists

is a step forward and establishes a foundation for further inquiry into the causes. Since the research on

public opinion and foreign investment has not addressed this question with a broad empirical study, this

work breaks new ground.

The topics of evaluations of national economic policy and attitudes about economic partners

have been explored in the literature on trade and immigration. This work will expand these theories to

consider how they apply to foreign direct investment. FDI is an understudied area of foreign economic

policy, and developing and testing a more comprehensive set of hypotheses is an important contribution

to research in this field.

28

VI.

Research Methodology

In order to test the hypotheses outlined above, I analyze variation in preferences on FDI using

public opinion surveys because these are the best way to directly measure how respondents in

developing countries think about FDI. There are relatively few surveys that ask questions about foreign

investment compared to other economic policies like international trade and foreign aid. The four

surveys in this analysis, three Latinobarometer Surveys and the Gallup 2006 Voice of the People Survey,

were selected because they provide the broadest coverage of developing countries and include the

necessary questions to test the hypotheses. These are the only cross-national surveys that ask

specifically about foreign investment rather than international trade or globalization, and the FDI

questions are only included in specific years. All years with FDI questions are included in this analysis.

The Gallup survey was conducted in 57 countries, including both developed and developing countries,

many of which have never been analyzed in studies of attitudes about globalization.' The

Latinobarometer surveys include 17 countries from Latin America. By studying many countries in

different years from 1995 to 2006, the survey analysis helps to assess the generalizability of the findings.

All surveys were administered across multiple countries using a random sampling procedure within each

country, so they allow for inferences about the entire population of each country. The survey analysis

tests the conventional wisdom that preferences on globalization are driven by economic self-interest in

relation to alternative explanations that national economic conditions, political ideology and antiAmericanism influence opinions about FDI.

The public opinion analysis examines variation on FDI preferences within each country, which is

useful for comparing how domestic groups with different characteristics feel about FDI. Since the

question wording is significantly different across surveys and none of these are panel surveys, the

I There are five additional countries with only partial survey responses to the Voice of the People survey, and they

are not included in the analysis.

29

analysis is not intended to compare responses over time. Instead, the focus of the analysis is on

variation in responses within each country during a given year when the survey was conducted. Groups

within a country are compared to each other. By using multiple surveys in a variety of countries and

time periods, the results are more generalizable than a single country study. In comparison to previous

research, the study is much more comprehensive and sheds light on FDI preferences in developing

countries such as Malaysia, Nigeria, and the Congo that are not typically included in studies of

globalization preferences.

This paper seeks to explain attitudes about FDI, so the dependent variable is the respondent's

attitude about foreign investment. In some models, the dependent variable is the attitude about

globalization, which includes FDI along with trade and other global flows. Attitudes are measured by a

dichotomous variable with a value of 1 indicating support and 0 indicating opposition to FDI or

globalization because the surveys only offer two choices. While the wording of questions differs across

surveys, the procedure for creating the dependent variable is the same. The data are limited by the fact

that respondents do not express the strength of their opinion. Those who strongly oppose foreign

investment are in the same category as those who slightly oppose it. While this is a simplification of real

preferences, it is typical for surveys to categorize opinions in this way, and respondents have the option

of stating they don't know or don't have an answer.

The regressions used in the survey analysis are probit models, which are a useful model for a

dependent variable that is between 0 and 1. In order to focus on variation within countries, dummy

variables for each country control for country-specific differences in levels of support for FDI. This

means that the variation analyzed in the model represents the difference within countries rather than

differences between countries. There is large variation between countries in levels of support for

globalization, which is highlighted in the descriptive statistics, but is not the focus of this study. The

analysis will compare the hypotheses about the determinants of opinions about globalization to

30

standard models that focus on economic factors. The independent variables used to test each

hypothesis depend on the survey and are described along with the control variables in each section

below.

Although survey analysis is one of the best methods for understanding individual opinions in a

large population, there are some limitations to this research methodology and to these surveys. By

design, surveys present a snapshot in time, so surveys from the late 1990s and early 2000s speak to

opinions at that time and are not designed to reflect current attitudes. However, at an aggregate level,

opinions on FDI are relatively stable. The responses to the FDI question in 1995 and 1998 for each

country have a correlation coefficient of .65, which means sentiment about FDI in 1995 is a strong

predictor of sentiment in 1998 in the same country. Since these surveys are not a true panel (a new

sample of respondents is selected each year), the data does not reveal whether individual opinions are

stable over time. Because the factor model is designed to be a universal theory of attitudes about FDI, it

should apply in any time period including the one studied here. It is useful to keep in mind that there

may be historical factors that influence opinions about FDI in a given period, but it is still possible to

analyze which model best explains attitudes about FDI and whether it fits in each of the years studied.

Since the data is cross-sectional and the independent variables are not randomly assigned, the

analysis is subject to the problem of endogeneity, also known as reverse causation. For example,

attitudes about FDI could influence citizens' views about the national economy, change their partisan

ideology, or generate anti-American sentiment. There may also be omitted variables that are related to

opinions about FDI and economic evaluations, ideology, or anti-Americanism, and these could be the

true determinant of FDI opinions. Each model includes standard demographic variables to control for

known factors that are associated with FDI preferences, but there could still be unobserved confounders

that were not measured in the survey. There is no way to control for endogeneity completely in the

current data, but a natural extension of this work would be to conduct a survey experiment. In a survey

31

experiment, one could randomly assign a treated group to a priming condition that evokes national

economic outcomes, partisanship, or nationalism before asking about FDI. Then responses could be

compared to a control group that is not primed to see the impact of each of these factors without facing

an endogeneity problem.

Despite the limitations of survey analysis using probit regression models, these remain a

standard tool for testing hypotheses about public opinion on policy issues. Because the Voice of the

People survey data has never been analyzed with regard to FDI, an initial cross-sectional analysis is

useful for understanding how well the current hypotheses explain FDI preferences. This initial

investigation provides the impetus for further study by uncovering the relationships in the data.

Understanding individual preferences is a starting point for explaining political behavior related to

globalization, such as protest movements and lobbying. It will inform future studies of FDI policy and

FDI flows that depend on an accurate understanding of public sentiment.

32

VII.

National Economic Evaluations and Support for FDI in Latin America

Latin America presents an interesting test case for understanding public opinion about foreign

investment because foreign investment has grown dramatically over the last 30 years in the region, but

globalization has been a contentious issue. During the 1990s, Latin American countries saw large

increases in FDI following major economic stabilization reforms that included privatizing many stateowned enterprises. These reforms were controversial at the time both because they involved the

privatization of state-owned assets, which raises ideological questions about the role of the government

in the economy, and because the privatization process meant significant job losses at a time of

economic austerity.

Following the peak of FDI inflows in the 1990s, Latin American countries have followed two very

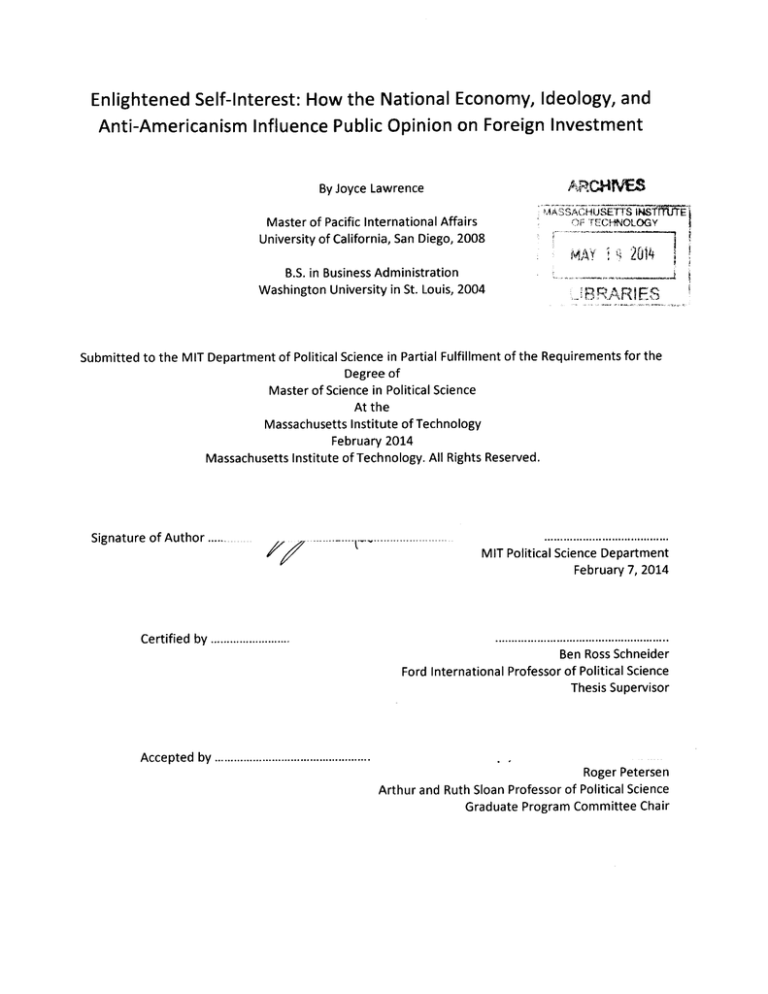

different paths. Figure 2 highlights the period of the survey analysis, 1995-2001, in which FDI levels

were high throughout Latin America with Chile reaching a peak of FDI inflows valued at 12 percent of

the country's gross domestic product (GDP). In the decade that followed, Latin American countries

diverged considerably. Chile now epitomizes a high-growth export-oriented development path and

Venezuela shows how a socialist revolution can reverse FDI inflows. On one hand, populist leaders like

Hugo Chavez, the late President of Venezuela, and Evo Morales, President of Bolivia, have alienated

foreign investors by nationalizing foreign assets and advocating for greater state ownership of domestic

resources. On the other hand, governments like those in Chile and Colombia have reoriented their

economic policy to take advantage of growing foreign investment and economic integration. The public

in Latin America is both skeptical of multi-national companies and eager to achieve economic growth

after experiencing many decades of economic boom and bust cycles.

Latin America differs from other regions because large amounts of the foreign investment

flowing into the region target primary materials and extractive industries, in which foreign ownership is

especially controversial. There is also a temptation to nationalize these industries when commodity

33

prices are high (Duncan, 2006), actions which are often accompanied by anti-globalization rhetoric.

Across the region, the type of FDI can vary considerably from mostly low-skilled maquiladoras producing

textiles in Central America to mining in Chile and manufacturing in Argentina. These differences will

certainly affect citizens' perceptions of foreign investment, and ultimately their support for it. However,

by looking at factors that influence opinions about FDI within countries, any aspects of FDI that are

unique to a country are the same across the survey respondents.

FDI Inflows as % of GDP

14.0

U2C

6.

0

(.05.

20.0%

-C -

C

-

-

--

-\C

u

Figure 2: FDI Inflows as % of GDP

One advantage of studying FDI preferences in Latin America is that data is readily available. The

Latinobarometer is an annual public opinion survey that has been conducted by the non-profit

Latinobarometer Corporation (Corporacidn Latinobar6metro) in 17 Latin American countries since 1995.

It investigates a variety of topics related to politics, the economy, and values. It is one of the few

surveys that includes questions about foreign direct investment, but these were only asked in 1995,

in

1998, and 2001, which is why this analysis focuses on those years. These surveys have been used

previous analyses of public opinion on foreign investment (Beaulieu et al., 2005; Pandya, 2010), but

previous studies did not consider the effect of national economic evaluations. The surveys are especially

34

useful for the purposes of this study because they ask about past, current, and future economic

conditions in addition to the standard covariates used in public opinion surveys on globalization. The

1995 survey includes 8 countries, and the 1998 and 2001 surveys include 17 countries, which are listed

in Table lError! Reference source not found.. Descriptive statistics for the variables used in the analysis

are given in Table 2.

Table 1: Latinobarometer Country Coverage

1995

x

1998

x

x

2001

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Ecuador

El Salvador

x

x

x

x

x

x

Guatemala

Honduras

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Country

Argentina

Bolivia

Brazil

Chile

Colombia

Costa Rica

Mexico

Nicaragua

Panama

Paraguay

Peru

Uruguay

Venezuela

x

x

x

x

x

35

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics of Latinobarometer Data

1995

Mean Std. Dev.

1998

Mean

Std. Dev.

2001

Mean

Std. Dev.

FDI

FDI BENEFICIAL

0.80

0.40

FDI ENCOURAGED

0.78

0.42

0.78

0.41

0.75

0.43

Education

YEARS OF EDUCATION

EDUCATION LEVEL

9.46

1.36

4.56

0.91

10.28

1.46

4.31

0.92

8.78

1.21

4.63

0.90

UNIVERSITY

SOME UNIVERSITY

0.11

0.09

0.31

0.29

0.13

0.15

0.33

0.35

0.07

0.10

0.26

0.29

VOCATIONAL TRAINING

0.22

0.42

0.21

0.41

0.22

0.42

0.21

0.40

0.21

0.41

0.19

0.40

JOB INSECURITY

0.84

1.20

2.21

0.99

2.17

1.02

WORKING

PUBLIC SECTOR

PRIVATE SECTOR

UNEMPLOYED

RETIRED

0.53

0.10

0.16

0.00

0.09

0.50

0.30

0.37

0.00

0.28

0.58

0.10

0.19

0.05

0.07

0.49

0.29

0.40

0.21

0.25

0.56

0.09

0.17

0.07

0.07

0.50

0.28

0.38

0.26

0.25

HOMEMAKER

0.24

0.43

0.19

0.39

0.21

0.41

STUDENT

PROFESSIONAL

BUSINESS OWNER

FARMER

0.08

0.02

0.08

0.01

0.27

0.14

0.26

0.10

0.10

0.02

0.06

0.01

0.30

0.13

0.23

0.10

0.08

0.02

0.07

0.03

0.27

0.14

0.25

0.17

SELF-EMPLOYED SALES

0.14

0.34

0.07

0.26

0.18

0.39

0.06

0.06

0.07

0.23

0.24

0.25

0.06

0.05

0.03

0.23

0.23

0.17

0.05

0.22

0.53

0.60

0.50

0.49

0.51

0.57

0.50

0.50

0.51

0.00

0.50

0.01

39.05

0.68

15.72

0.47

38.23

15.12

38.67

15.96

2.48

0.14

0.73

0.35

0.17

0.38

0.14

0.35

0.50

0.50

0.49

0.50

0.52

0.50

2.50

0.76

0.99

2.92

0.88

1.19

0.17

0.90

0.77

0.79

0.79

0.73

0.75

2.40

0.65

0.88

2.94

0.87

1.12

0.91

0.68

0.77

0.83

0.68

0.75

2.21

0.36

0.47

2.85

0.40

0.59

0.91

0.58

0.61

0.82

0.61

0.67

SECONDARY

Occupation

MANAGER OR EXECUTIVE

WORKS IN OFFICE

WRITING & NUMBERS

Demographic

FEMALE

MARRIED

AGE

HOMEOWNER

Ideology

NATIONAL PRIDE

LEFT

RIGHT

Economics

NATIONAL ECONOMY

NATIONAL ECONOMY

NATIONAL ECONOMY

PERSONAL ECONOMY

PERSONAL ECONOMY

PERSONAL ECONOMY

DECLINE

CURRENT

CHANGE

FUTURE

CURRENT

CHANGE

FUTURE

36

0.38

There are two different questions that ask about opinions on FDI. These are used to construct the

dependent variables FDI BENEFICAL and FDI ENCOURAGED in the model. In the 1995 and 1998 survey,

the question reads "Do you consider that foreign investment, in general, is beneficial or is harmful to the