Journal of Youth Development Bridging Research & Practice

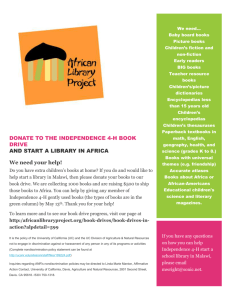

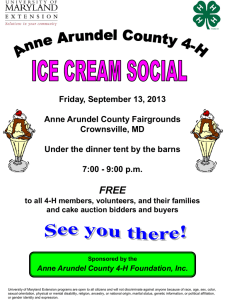

advertisement