The Movement of Natural Persons Final Report

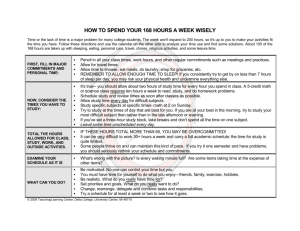

advertisement