Document 10585735

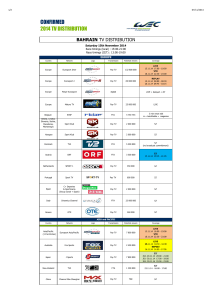

advertisement