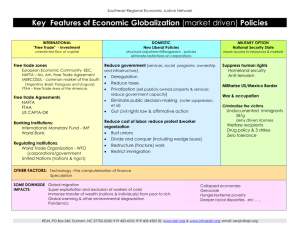

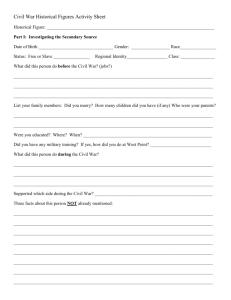

Regionalism versus Globalization in the Americas:

advertisement