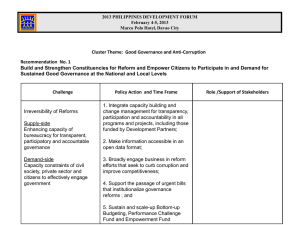

Governance and Anti-Corruption Reforms in Developing Countries: Policies, Evidence and Ways Forward

advertisement