(1966)

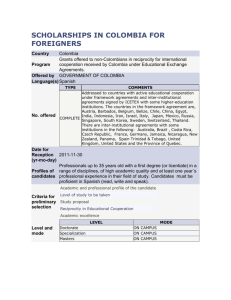

advertisement