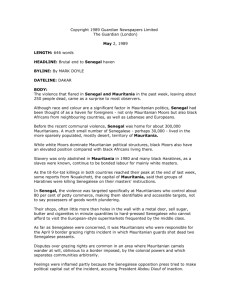

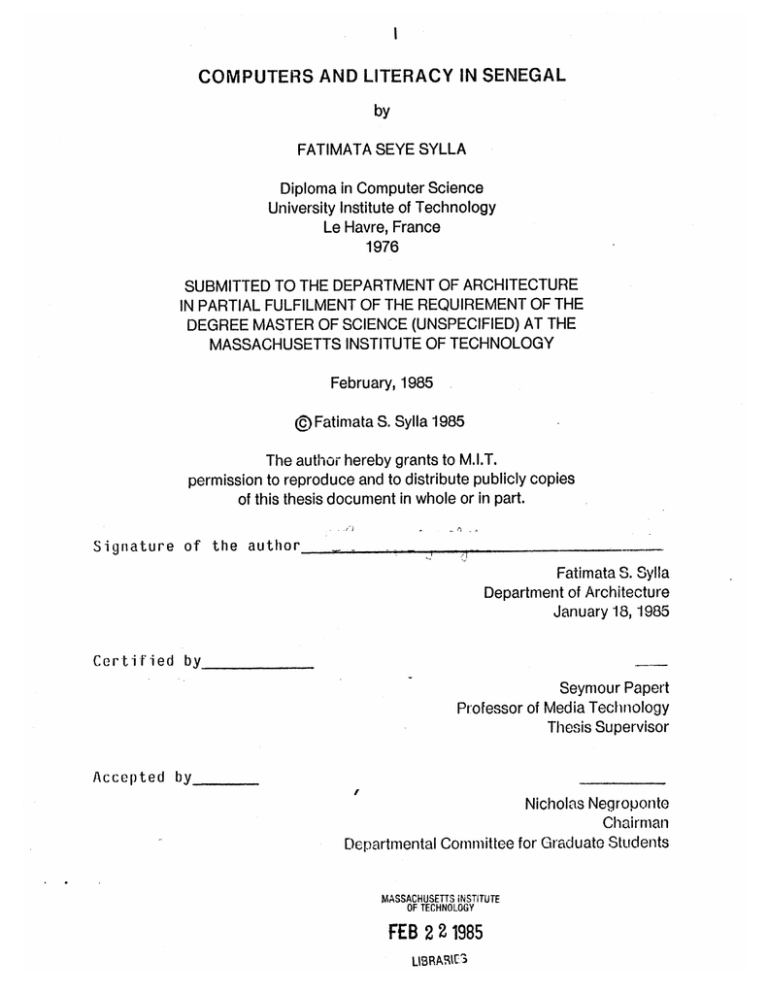

COMPUTERS AND by FATIMATA SEYE 1976

advertisement