Green Rebuilding the South Bronx:

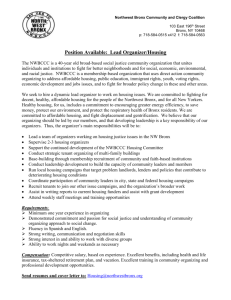

advertisement