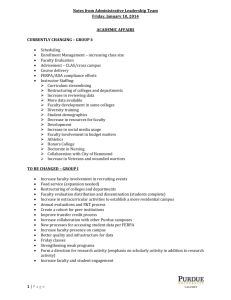

The Completion Arch nr

advertisement