Document 10571941

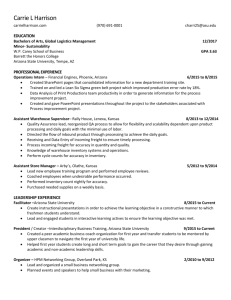

advertisement