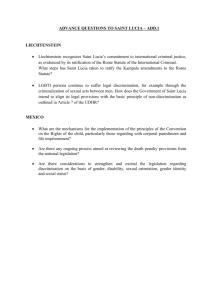

St. Lucia: 2005 Article IV Consultation—Staff Report and Public Information... on the Executive Board Discussion.

advertisement