IDB COUNTRY STRATEGY WITH JAMAICA (2006-2009)

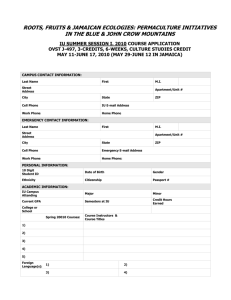

advertisement