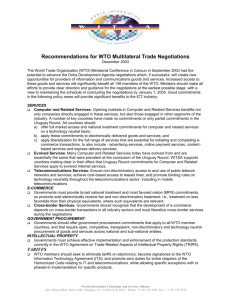

THE AGREEMENTS The WTO is ‘rules-based’; its rules are negotiated agreements

advertisement