SKIN FLICKS By 1986

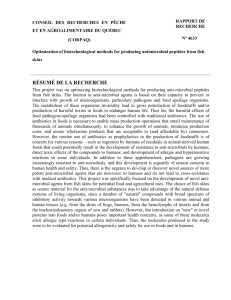

advertisement