Self Help Support System The New York

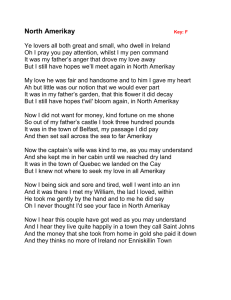

advertisement