IN

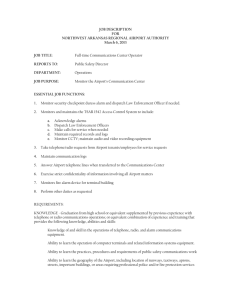

advertisement