HOUSING DESIGNS AT ROBERT TODD HAMILTON

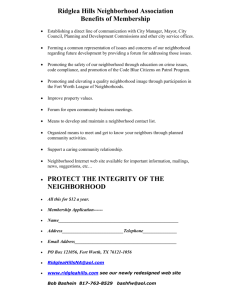

advertisement