Document 10558698

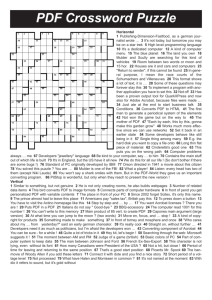

advertisement