The case for transition to a sustainable transport system in Stellenbosch

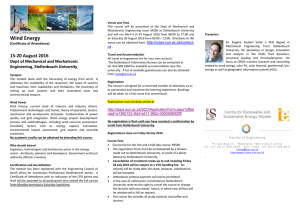

advertisement