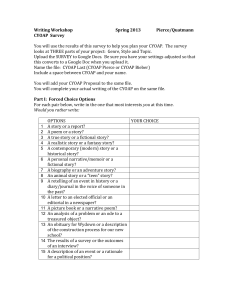

A

advertisement