"SUCCESS" TANAKA AND PLANNING

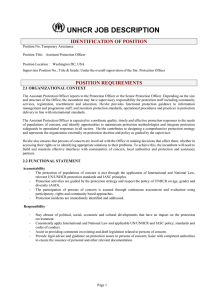

advertisement