DEVELOPING THAN by Frances Washington Ferguson

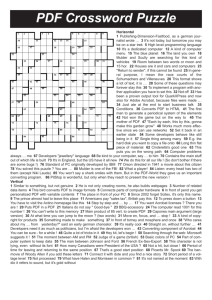

advertisement