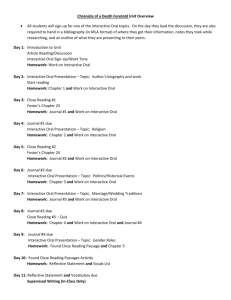

by D. B.A., American Studies and Computer Applications 1997

advertisement