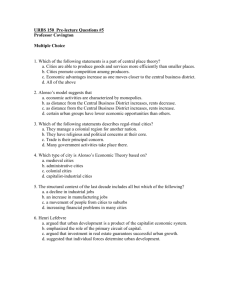

INTERNATIONAL REAL ESTATE INVESTMENTS: By C.

advertisement