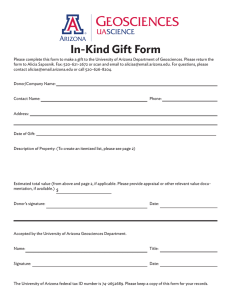

The College of Agriculture and Life Sciences:

advertisement