Ending Teen Homele

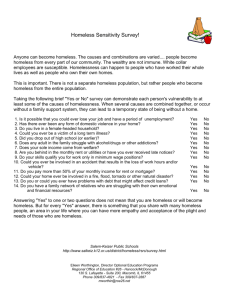

advertisement