II Engendering Design:

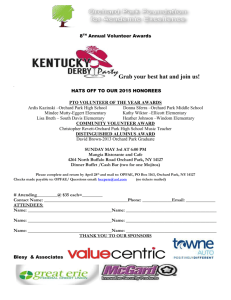

advertisement