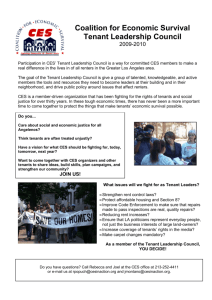

9

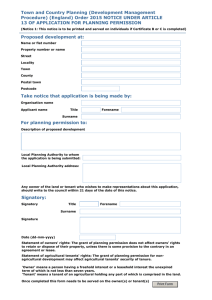

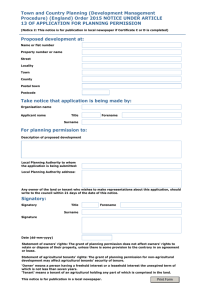

advertisement