Recommendations to the Campus Committee: An Organizing ... of Springfield, MA

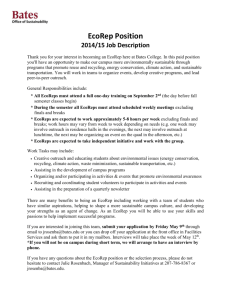

advertisement