Document 10534654

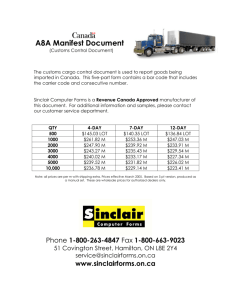

advertisement