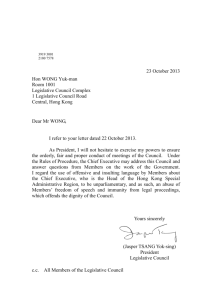

TD United Nations Conference on Trade and

advertisement