Floral and Attendant Faunal Changes on ... Rio Grande Between Fort Quitman and ...

advertisement

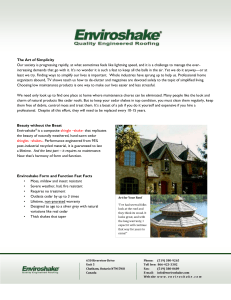

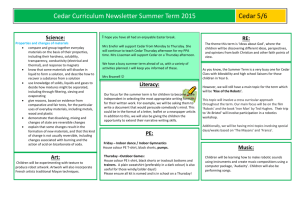

it r. Floral and Attendant Faunal Changes on the Lower Rio Grande Between Fort Quitman and Presidio, Texas 1 I­ Ll Ronald W. Engel-Wilson and Robert D. Ohmart 2 Abstract.--Written and photographic documentation from explorers and settlers demonstrate that the floodplain was historically dominated by cottonwood-willow (Populus fremontii­ Salix gooddingii) and screwbean mesquite (Prosopis pubescens) communities. Past and present land and water use practices have resulted in an almost complete elimination of native tree species and a dominance by the exotic salt cedar (Tamarix chinensis). Avian census data from the area show higher bird population densities and diversites in the select mature cottonwood-willow communities than in mature salt cedar communities. INTRODUCTION This paper examines historical records containing vegetation descriptions for the Rio Grande from Presidio to Fort Quitman, Texas, and compares past vegetation with current vegetative conditions. The bird species in existing plant communities are examined, and changes in avifaunal diversities and densities since European settlement are evaluated based on our premise that as plant communities change through time so do the attendant bird species. The correlation of riparian habitats and high avifaunal densities and diversities has been documented numerous times (Carothers 1977, Hubbard 1977, Anderson et al. 1977b, Stevens et al. 1977, and Wauer-1977) • Andersonet-;1. (1977b) found that avian use of the exoti~salt cedar (Tamarix chinensis) on the Colorado River was lower than avian use of native riparian habitats, and this general lPaper presented at the National bymposium on Strategies for Protection and Management of Floodplain Wetlands and other Riparian Ecosystems, Pine Mountain, Georgia, December 11-13, 1978. , .j. 2Respectively, Graduate Student, and Associate Professor of Zoology, Arizona State University, Department of Zoology and Center for Environmental Studies, Tempe, Arizona 85281. trend has also been observed on the Rio Grande. More avian habitat specialists were found in cottonwood-willow (Populus fremontii-Salix spp. ) .·.and screwbean mesquite (Prosopis pubescens) communities during the winter than any other community type; yet in aerial extent these two communities covered less than 40 ha within a 20,000 ha study area (Engel-Wilson and Ohmart 1978). This is highly important in view of the decreasing area of native riparian habitat and its replacement with agriculture or salt cedar (Robinson 1965, Harris 1966, and Horton 1977). Historically the trade route along the Rio Grande from Presidio to Fort Quitman, Texas, was traveled infrequently due to the rugged terrain and hostile Indians. The narrow and densely vegetated floodplain paralleled by the rugged upland terrain made travel difficult and frequently impossible, so few travelers visited the area. Consequently early accounts are scarce, but they do describe the nature of the riparian plant communities that occupied this floodplain. Spaniards were the first Europeans to establish settlements on this section of the Rio Grande. Forts and missions were estab­ lished at Presidio as early as 1609 (Bancroft 1886) and at El Paso in 1683 (Espinosa 1940). In 1582 an early Spanish explorer, Espejo (Hammond 1929), wrote of the extent of the This research was supported by International Boundary and Water Commission grant IBM 77-17. 139 Saturday, March 3l •.. 0n our left on the opposite bank is the North end of the Sierra Grande [,Sierra Alto]. On our right [is] a high and large mountain which I have called "Mount Barnard" [Chinati Peak]. The travel has been much inter­ rupted by chaparral, the cactus in every variety, enormous palmitios from fifteen to twenty-five feet high, and every kind of thorn. vegetation and the plant communities of the Rio Grande just above San Bernardino (now Presidio, Texas). He stated: It is such a river that all of these three leagues [in width] [1 league=:4 km] are covered with numerous groves of poplars and willows there being in it very few willows or any other sort of trees. In 1846 Whiting (Bieber 1935) wrote of the vegetation he saw along the river during his march to establish a wagon route from San Antonio to El Paso as he followed the Rio Grande from Presidio northward (Fig. 1). Uni ted Monday, April Z•.• On account of the under­ growth and the willow, our progress was laborious and slow, and in many places we were forced to the hills ••• the Rio Grande with its pale green fringe of cottonwoods and willows, formed a pleasant picture. Towards dusk we reached a bottom where though the grass was poor, we were obliged to camp. Thursday, April 5 .•• we saw a beautiful valley with its usual clothing of cotton­ wood, stretching to the northward •.. To our right now lies .•. a rugged and high mountain ••. this I called "Mount Chase." [Eagle Mountain]. Monday, April 9 •.. continued the march in one unbroken valley, through broad and level bottoms heavily timbered with large cottonwoods ... we saw a flock of twenty-five huge white pelicans .•. Three large,black-tailed deer, the mountain species were wounded ..• At four the march was resurned ••. still in the extensive groves of alamos [Cottonwoods], becoming wider as we advance. In this tract the grass is generally poor •.. States N Mexico • Chlnat I P•• II S Ie'" AIIO' MI. ',5 Tuesday, April lO •.• Our trail still lay in the broad cottonwood bottom. The soil, nearly destitute of grass, ... Wednesday, April 11 .•• This trail lies through a fine tract, heavily timbered--the trees are very large. We saw nothing of the southern chaparral and undergrowth to impede us ... We are now opposite to the island called "La Isla" ••. [near San Elizario] a mexican visited our camp ••• told us we were thirty miles from El Paso. 3p Figure I.Map of the Rio Grande from El Paso to Presidio, Texas. He viewed the floodplain from a hill over­ looking Presidio and Ojinaga, Chihuahua and wrote: Saturday, March Z4 ••• We soon carne in view of the Rio Grande with its green valley and cottonwood groves. Friday, March 30 •.. Nearly opposite the Mexican town we passed a fine part of the valley where the mesquite, the willow and cotton­ wood abound in size, and where some judicious and tasteful clearing would make a pleasant site for quarters of a post, ••• Our trail ..• between cottonwoods, which almost everwhere line the banks of the river, and the gravel ridges which put out from the hills or rather mountains [Chinati Mountains] on the right. The flora of this section of the Rio Grande Valley was described by Dr. Parry who accompanied the United States and Mexican boundary survey in 1857. In the valley of the Rio Grande we frequently find a heavy growth of cotton wood and willows. The "screw bean," Strombocarpa pubescens, often occupies large tracts, accompanied by a dense undergrowth of Baccharis salicina. The low saline places produce an abundance of ~ canescens, while on the higher 140 ground Tessaria borealis is a common plant. (Emory 1859). probably le~s than 800 ha under production, the remaining being fallow or in pasture. The early descriptions of Espejo and Whiting indicate there was little change in the vegetation along the Rio Grande between 1582 and 1846. Farming and livestock operations were initiated by the Spanish in the late 1500's and reached their zenith in the late 1800's and early 1900's. By the early 1900's much of the bottomland vegetation, mostly cottonwoods, had been removed to develop the riparian floodplain for agricul­ tural purposes (Horton 1977), building material (Emory 1859), livestock forage (Galvin 1966), and fuel. Due to the decrease in agricultural activity, the floodplain was left open for the invasion of the exotic salt cedar (Harris 1966, and Robinson 1965) (Plate 2). Cotton­ woods and willows were unable to grow in their former areas because 1) the abandoned soils were not suitable, 2) the water quality and availability were inadequate, and 3) annual floods had been stopped thereby eliminating soil suitable for seed propagation. The very nature of salt cedar growth along intermittent river courses helps salt cedar disperse into low-lying farmland. Intermittent flows allow seedlings to invade the channel during reduced flows, and when the water is high the seedlings trap the sediment. Annual repetition of this process eventually results in soil and vegetation blocks in the channel, which causes channel shifts and flooding of adjacent areas (Robinson 1965, and Harris 1966). Photographs of the area in 1918-1919 show a dramatic change in the vegetation of the alluvial floodplain from that described by Whiting in 1849. The only remaining cotton­ woods and willows wer.e those along the river and along the margins of the fields (Plate 1). I I An assessment of the plant communities in the study area, from March 1977 to March 1978, demonstrated there has been a drastic change in species composition and aerial extent of the native plant communities during the past century. The degree of clearing in the valley was determined by comparing hectares under cultivation in the early 1900's to the present time. The total area under cultivation in 1928-1930 was 7,280 ha (IBWC 1978), and by 1977 this had dropped to 4,700 ha (Engel-Wilson and Ohmart 1977). Peak values for Mexico were 6,228 ha in 1949 (IBWC 1978). The total cleared may be somewhat less than the sum of the two extremes due .to boundary shifts. shifts. Plate 1. Candelaria 1918. Looking down river one can see numerous large cottonwoods and much agricultural activity. The s1!bsequent decline in agriculture appears to be due to several factors and/or a combination there of: 1. Increased use of water upstream 2. Construction of dams upstream (Elephant Butte 1919 and Caballo 1938) 3. Economic depression of the 1930's 4. Floods of 1942 and 1966 5. Increased salt accumulations in floodplain soils which reduced agricultural productivity Although there are 4,800 ha (23 percent of the floodplain) of recognized agricultural land in the valley, it is noteworthy that there are Plate 2. Candelaria 1974. Most of the vegetation is salt cedar with little riparian vegetation. 141 In the study area in 1977 there were 5,600 ha of salt cedar which comprised about 27 percent of the floodplain vegetation (Engel-Wilson and Ohmart 1977). Only about 12 ha of mature cottonwood and willow persisted which made up only 0.06 percent of the flood­ plain. This did not include isolated indiv­ iduals along canals and fields. Plates 1 and 2 contrast the abundance of cottonwood in 1918 versus 1974. The remaining flood­ plain was made up of a mixture of honey mesquite (Prosopis velutina) and other desert shrubs (9600 ha or 46 percent). association of trees, shrubs and forbs. Percent ground cover for the most common plants are: cottonwood 5 percent, willow 14 percent, salt cedar 7 percent,seepwillow (Baccharis spp.) 17 percent, Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense) 34 percent and dock (Rumex spp.) 32 percent. -----The relative foliage volume (RFV) in the salt cedar community was 2.848 m2 /m 3 with 0.256 m2 /m 3 RFV above 7.5 m with no vegetation above 9 m. The RFV in the cottonwood-willow community was 6.208 m2 /m S with 0.499 m2 /m 3 RFV above 7.5 m and having vegetative volume occuring up to 12 m. Methods Birds A survey of historical literature and photographs was conducted in the libraries of Arizona State University, University of Texas at El Paso, and El Paso City. Transects were established in nine mature salt cedar communities comprising a total of 150 ha. One transect of 10 ha was established in a cottonwood-willow association. These areas were sampled for bird densities each month for one complete year using the Emlen (1971) technique (Anderson, etal. 1977a) Densities were expressed as the numbe;-of birds per 40 ha and presented as monthly means for each of five seasonal groups: March-April (MA); May through July (MJJ); August-September (AS); October-November (ON); and December through February (DJF). Species which occurred in fewer than two seasonal groups for both community types were not used in the comparisons. Also ducks, herons and rap tors were excluded from the analysis. Foliage Height Diversity (FHD) and relative foliage volume (RFV) were measured in each community using the board technique (MacArthur and MacArthur 1961). Percent ground cover was estimated using a 5 m2 area. Percent ground cover by plant species was estimated to the nearest 5 percent in the 5 m2 plots. Plots were located 5 m to the right and left of the transect on 61 m spacing beginning at 15 m from the beginning of the transect. The sums of the percentage for each plant species for aztransect was divided by the number of 5-m 's to derive the mean percentage of each plant species for the transect. RESULTS Vegetation Salt cedar forms a dense monotypic stand with 91 percent ground cover and only traces of annuals, forbs and other shrubs. The cottonwood-willow community is a multi-layered 142 The highest number of species occurred in salt cedar during March-April (see Table 1). The lowest numbers of species (17) were detected in the cottonwood-willow association (Table 1) in these same two months. In par~ the latter may be an artifact of the small number of samples from the cottonwood-willow community at the beginning the study. The number of species recorded in low densities (i.e. < 1/40 ha) in salt cedar was 10 and one in cottonwood-willow in MA. If very low density species are ignored, the number of species seen in salt cedar versus cottonwood­ willow during MA is reduced to 16:20. In the remaining seasons, little fluctuation in the number of species in the cottonwood-willow community was observed (27 May through July, 26 August through September, 27 October through November, and 23 December, January, and February). 0; Densities were low for both communities in MA (475 CW, 330 SC), but increased to a peak in SC in MJJ (486) and to an AS peak (749) in CWo Both communities had decreased densities in ON 06 SC, 569 CW) and densities in SC continued to decline in DJF (67). How­ ever avian densities in CW increased to 744/40 ha in DJF due primarily to the influx of granivores and small insectivores. Differences in the bird populations of these two communities became more striking when a large portion of the dove population was removed from the consideration. Doves gain only a small fraction of their total food intake in the communities in which they nest, consequently we feel a reduction of 90 percent of the doves is ecologically valid. The difference in total birds with this adjustment is dramatic between cottonwood-willow and salt cedar in MA (418 to 181) MJJ (598 to 262) and ON - (657 t6 80), respectively. Salt cedar appears to be very good nesting habitat for White­ winged Doves as they reached nesting densities in the Candelaria area of 28 nests per season Table 1. Bird densities (1/40 hal by month group for cottonwood-willow (CW) and salt cedar (se) communities on the Rio Grande at Fort Quitman. MA' cw I Gambel Quail (Lophortyr gambeliil A-S' MJJ' cw SC II I SC II 13 23 cw I DJF' O-N' SC II CW I SC II 35 81 CW I SC II 58 0 Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura) 9 17 16 28 27 9 15 o o 0 White-winged Dove (Zenaida asiatica) 53 149 107 221 76 100 0 o o 0 o o 016 o 1 600 o o 0 10 1 o o o 0 Roadrunner (Geococcyx calfgonianus) o Yellow-billed Cuckoo o 0 38 33 Ladder-backed Woodpecker (Picoides scalaris) 6 1 Common Flicker (Calaptes auratus) o Ash-throated Flycatcher (Hylarchus cinerascens) o Say Phoebe (Sayornis 3 o o o (COCCYZUS o a1'llericanus) Black-chinned Hummingbird (Archilocus alexandri) 19 6 3 o 11 o o o o 1 o 2 o o o o o o o o 11 o 0 o 1 ~) Black Phoebe (Sayornia nigricans) Vermilion Flycatcher (pyrocephalus rubinus) 40 11 6 o 4 0 o o 0 o o 4 o 29 4 o Verdin (Auriparus flariceps) 8 1 o 2 18 4 29 o o o o o 6 o o o o o 0 o o o 10 17 13 8 o o o 18 6 0 50 17 93 6 o o 0 o o o 0 1 o 0 237 0 3 13 26 Black-taile~' o o o 5 o Ye110w-rumped Warbler (Dendroica coronata) o 130 o 20 o Bell Vireo (Vireo bellii) Lucy Warbler (Vermivora luciae) 1 o Cliff Swallow (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) Gnatcatcher (Polioptlla melanura) 12 0 Orange-crowned Warbler (Vermivora ce1ata) o Yellowthroat (Geoth1ypis trichas) o Yellow-breasted Chat (~ virens) o 17 94 55 54 11 Swmner Tanager (Piranga !.!!l!!!!.) o 16 29 29 32 11 80 10 116 16 50 4 12 o o o o 41 o 42 0 o o o o 17 1 6 0 HOuse Finch (Carpodacus mexicanus) Brown Towhee o (Pipilo fuscus) Green-tailed Towhee (Pipilo ch10rurus) Cardinal (Cardinali. cardinalis) Painted Bunting (Passerina ciria) o o o 8 o o 143 o o 38 10 32 2 o 31 o o 0 Table 1 (continued) MJJ' HA' cw cw SC II I II cw DJF 5 o-N' A-S' SC SC CW SC CW o 18 SC II II II o o 1 o o o Long-billed Harsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris) o o o o o o 11 o 13 0 Bewick Wren (Thryo....nes bewickii) 2 3 1 2 o 3 38 8 22 9 Mockingbird (M1mus polyglottos) 3 4 6 6 1 0 o o 0 Crisssl Thrasher (Toxostoma dorsale) o o o 1 12 Hemi t Thrush o o o o o o Northern Oriole (~ galbula) o o 2 1 o o o o 0 orchard Oriole (~ spurius) o 1 48 8 28 o o o 0 Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) 1 14 11 5 6 o o o o 0 Great-tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) o 9 11 15 52 o 3 o o 0 Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) o 53 28 2 o o o o 0 Loggerhead Shrikp (Lanius ludovicianus) o o o o 2 1 o o 0 12 4 o o o o 41 24 64 32 o o 29 4 56 o o o 0 o o 25 6 40 1 o 0 White-crowned Sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys) 35 o 1 o o o 139 1 108 5 White-throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis) o 5 o 1 o o o o o 0 29 o o o o o 58 o 2 o o o o o o 17 o 31 0 o o o o o o 12 o 43 0 House Wren (Troglodytes aedon) (~ o 1 o guttatus) Ruby-crowned Kinglet (!!&ullls calendula) Blue Grosbeak (~ caerulea) Lesser Goldfinch (carduelis psaltda) Chipping Sparrow (Sp1:<ella passer ina) Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodis) Swamp Sparrow (Melospi za georgiana) 17 30 27 28 26 25 27 20 23 13 475 330 708 486 749 178 569 76 744 67 419 181 80 556 76 744 67 Diverei ty All Bird. 598 2.670 657 2.243 2.248 2.160 2.8401.9262.7502.2672.3811.795 % of Max 0.792 0.660 0.810 0.648 0.8720.5980.8340.757 0.759 0.700 Diversity 10% Doves 2.124 2.879 2.659 2.737 2.7902.8532.7142.267 2.3811.795 % of Max 1 March to April 0.821 0.855 0.886 0.823 0.757 0.759 0.700 It 0.804 0.750 0.846 Oc taber to November 5 December, January, and February N..... ered Species Dens ity All Birds '1 40 ha Denisty 10% Doves , Hay, June. and July , August to Septe1llber 144 262 important has been the invasion of the exotic salt cedar. Salt cedar has the ability to colonize areas after summer rains because its flowering and fruiting cycles are such that there is a continual supply of seeds to germinate when the soil is moist (Harris 1966). Once a dense carpet of salt cedar seedlings has developed little light penetrates to the soil for germinating cottonwoods or willows. Should the latter germinate and survive, the future of cottonwoods is bleak, for in a few years the debris laden community burns. Fire encourages the dominance of salt cedar by removing other species which are less fire adaptive (Ohmart, Deason, Burke 1977). Salt accumulations (discussed by Ohmart et al. 1977) may also have played an important role­ in the elimination of cottonwoods as sediments clogged the channel and spread salt-laden waters laterally. per 0.4 ha and population densities of 506 per 40 ha (Engel-Wilson and Ohmart 1978). Bird species diversities in CW were higher than those in SC when all birds were included. The diversity in SC was higher than that in CW when 10 percent of doves were used in the calculation. Bird species diversities in CW ranged between 87 percent (AS) and 76 percent (DJF) of maximum when all birds were used and slightly lower when 10 percent of the doves were used. In SC BSD percent of maximum increased in MA, MJJ, and AS when 10 percent of doves were used in the calculations 65 to 82 percent MJJ, and 60 to 87 percent AS. Both communities were compared for each seasonal group using a formula of ecological overlap (Horn 1966). The salt cedar overlap with cottonwood-willow was lowest in MA at 50 percent (see Fig. 1) and highest in MJJ at 85 percent. After the peak in MJJ overlap decreased to 70 percent AS, 65 in ON and to 62 percent DJF. Conclusion Historically the study area along the Rio Grande had large and extensive tracts of cottonwoods. Past records also demonstrate that little change occurred until after the mid 1800's, when the area became settled and the alluvial floodplain converted to agriculture. By the turn of the century most of the native riparian vegetation had been cleared. Today there are scattered remnants of the native vegetation, and isolated cottonwoods have been spared along the edge of fields or canal banks to offer shade for domestic livestock or workers during the hot summer months. Man's activity in the valley brought about the removal of much of the cottonwood-willow community. The few remaining trees continue to flower and fruit, and an occasional seedling can be found. But intensive grazing by domest~c livestock quickly eliminates any cottonwood seedling or sucker that appears. Cottonwoods are not the only vegetation which is browsed in the area. Cattle and goats were observed eating yucca (Yucca spp.), ocotillo (Fouguieria splendens), prickley pear (Opuntia spp.), and crown of thorns (Koberlinia spinosa). Overgrazing has been one factor which has prevented reproduction of the cottonwood-willow community in the area. A second factor has been the reduction of flows and the elimination of flooding during the time in which cottonwoods and willow seeds are viable. Cessation of flooding is the result of increased water use and the construction of dams upstream. Also 145 With the loss of the cottonwood-willow community and its replacement by salt cedar, there was a change in the vertebrate populations. Salt cedar has a high total bird population in the breeding season (mostly doves), but during the winter the densities are very low. Cottonwood-willow communities not only contain a higher density of birds than salt cedar but also support a higher species diversity and richness. This same pattern was found in these two communities on the Colorado River (Anderson and Ohmart 1977). Several species in the study area have a high affinity for the cottonwood-willow association. These are the Brown Creeper (Certhia familiaris), Common Flicker (Colaptes auratus), Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius). porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum), and beaver (Castor canadensis). These species occur in very low densities and will probably disappear as cottonwoods are extirpated. Other bird species which will be reduced in density with the demise of the cottonwood­ willow community are orioles (Icteridae), Cardi~als (Cardinalis cardinalis), many species of warblers (Parulidae), Lesser Goldfinches (Carduelis psaltria), Long-billed Marsh Wrens (Cistothorus palustris), and some sparrows (Fringillidae). Mammalian species associated with the cottonwood-willow community, such as the cottonrat (Sigmodon hispidus), house mouse (Mus musculus), and harvest mouse (R;[throdontomys megalotis) will suffer a similar fate. Such species as the Black Hawk (Buteogallus anthracinus), Yellow Warbler (Dendroica petechia), and arboreal lizard have already been extirpated in the area. A 442 km reach of river that was once dominated by cottonwoods and willows has been reduced to a few ha of this community. Unless action is taken to preserve the remnant areas of cottoriwoods and willows and plant others; Bieber, R. P. ed. 1935. Exploring southwest trails, 1846-1854. A. H. Clark, Glendale, California, Vol. 7, pp. 243­ 350. and protect them from livestock and fire, the remaining trees will eventually die, leaving no successors. Plantings of cottonwoods should be an integral part of any federal. or state project conducted in this or any other part of the Rio Grande. Carothers, S. W. 1977. Importance, preser­ vation and management of riparian habitat: An overview. In Importance, Preservation and Management of Riparian Habitat: A Symposium. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Report RM-43. p~ 2-4. At present only a few of the species that are designated as endangered by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1977 live in cottonwood-willow communities. But as these habitats continue to be eliminated throughout the Southwest the species that are restricted to these habitats may very well be reduced in number so that they are classified as rare or endangered. Emlen, J. T. 1971. Population densities of birds derived from transect counts. Auk 88: 323-341. Johnson et al. (1977) stated that riparian habitat"s were the most productive and poss:lbly the most sensitive habitat's inNorth America. He recommends that they should be managed accordingly. It is our opinion that Johnson's recommendations be followed. One of the first steps would be to initiate efforts to have cottonwood-willow associations and water dependent communities in the Southwestern United States placed on record as being endangered habi ta t's. These areas should have the same protection as that accorded endangered plants or animals. LITERATURE CITED Anderson, B. W., R. W. Engel-Wilson, D. Wells, and R. D. Ohmart. 1977a. Ecological study of southwestern riparian habitats: techniques and data applicability. In Importance, Preservation and Management of Riparian Habitat: A Symposium. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Report RM-43. pp. 146-155. Anderson, B. W., A. E. Higgins, and R. D. Ohmart. 1977b. Avian use of salt cedar communities in the lower Colorado River Valley. In Importance, Preservation and Management of Riparian Habitat: A Symposium. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Report RM-43. pp. 128-131. Anderson, B. W., and R. D. Ohmart.1977c. Vegetative structure and bird use in the lower Colorado River Valley. In Importance, Preservation and Management of Riparian Habitat: A Symposium. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Report RM-43 pp. 23-34. Emory, W. H. 1859. House Ex. Doc. 135, 34th Congress, 1st session. Report on the United States and Mexican Boundary Survey. Washington, D. C. 2 vols. Engel-Wilson, R. W., and R. D. Ohmart. 1977. Unpubl. vegetation type map submitted to International Boundary and Water Commission, El Paso, Texas. Engel-Wilson, R. W., and R. D. Ohmart. 1978. Assessment of vegetation and terrestrial vertebrates along the Rio Grande between Fort Quitman, Texas ano Haciendita, Texas. Final unpub1. report submitted to International Boundary and Water Commission, El Paso, Texas. . Espinosa, M. J. (Tr.) 1940. First expedition of Vargas into New Mexico, 1962. The University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, N.M. Galvin, J.(ed.)1966. Western America in 1846-1947. The original travel diary of Lt. J. W. Abert who mapped New Mexico for the U. S. Army. John Howell-­ Books. Hammond, G. P., and Agaspito Rey (Tr) 1929. Expedition into New Mexico made by Antonio De Espejo 1582-1583. The Quivira Society Los Angeles. 143 pp. Harris, D. R. 1966. Recent plant invasions in the arid and s.emi-arid southwest of the United States. Annals of the Assoc. of Amer. Geographers 56(3):408-422. Horn, H. S. 1966. Measurement of "overlap" in comparative ecological studies. Am. Nat'l. 100:419-424. Bancroft, H. H. 1886. History of the North Mexican States and Texas. San Francisco: The History Company, Publ. 1886. 2 vols. 146 in -4. 1 7. 78. ia1 aen i Horton, J. S. 1977. The development and perpetuatjon of the permanent tamarisk type in the phreatophyte zone of the southwest. In Importance, Preservation and Management of Riparian Habitat: A Symposium. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Report RM-43. pp. 124-127. Hubbard, J. P. 1977. Importance of riparian ecosystems: Biotic considerations. In Importance, Preservation and Management of Riparian Habitat: A Symposium. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Report RM-43. pp. 14-18. International Boundary and Water Commission. 1974. Unpubl. data. Aerial photo. International Boundary and Water Commission. International Boundary and Water Commission. 1978. Unpubl. data. International Boundary and Water Commission, E1 Paso, Texas. Johnson, R. R., L. T. Haight: and J. M. Simpson. 1977. Endangered species vs. endangered habitats: A concept. In Importance, Preservation and Management of Riparian Habitat: A Symposium. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Report RM-43. pp. 68-79. MacArthur, R. D., and J. W. MacArthur. 1961. On bird species diversity. Ecology 42:594-598. Ohmart, R. D., W. O. Deason, and C. Burke. 1977. A riparian case history: The Colorado River. In Importance, Preservation and Management of Riparian Habitat: A Symposium. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Report RM-43. pp. 35-47. Robinson, T. W. 1965. Introduction, spread and aerial extent of salt cedar (Tamarix) in the western United States. USGS Prof. Paper 491-A. 12 pp. Stevens, L., B. T. Brown, J. M. Simpson, and R. R. Johnson. 1977. The importance of riparian habitat to migrating birds. In Importance, Preservation and Management of Riparian Habitat: A Symposium. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Report RM-43. pp. 156-164. Wauer, R. H. 1977. Significance of Rio Grande riparian systems upon the avifauna. In Importance, Preservation and Management of Riparian Habitat: A Symposium. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Report RM-43. pp. 165-174. ion 11-­ f :lC. " 147