Biomass and Bioenergy Resource Assessment State of Hawaii

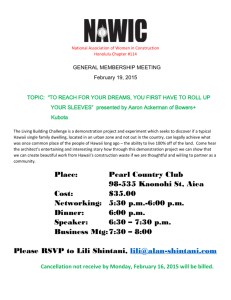

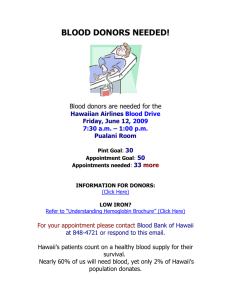

advertisement