66, 3 (2014), 283–293 September 2014 ON SOME NEW MIXED MODULAR EQUATIONS

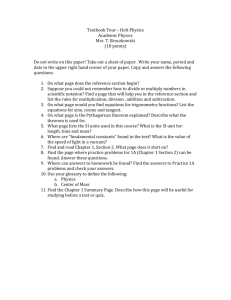

advertisement

MATEMATIQKI VESNIK

originalni nauqni rad

research paper

66, 3 (2014), 283–293

September 2014

ON SOME NEW MIXED MODULAR EQUATIONS

INVOLVING RAMANUJAN’S THETA-FUNCTIONS

M. S. Mahadeva Naika, S. Chandankumar and M. Harish

Abstract. In his second notebook, Ramanujan recorded altogether 23 P –Q modular equations involving his theta functions. In this paper, we establish several new mixed modular equations involving Ramanujan’s theta-functions ϕ and ψ which are akin to those recorded in his

notebook.

1. Introduction

Following Ramanujan, let (a; q)∞ denote the infinite product

q are complex numbers, |q| < 1) and

f (a, b) :=

∞

P

∞

Q

(1 − aq n ) (a,

n=0

an(n+1)/2 bn(n−1)/2 , |ab| < 1,

n=−∞

denote the Ramanujan theta-function. The product representation of f (a, b) follows

from Jacobi’s triple product identity and is given by:

f (a, b) = (−a; ab)∞ (−b; ab)∞ (ab; ab)∞ .

The following definitions of theta-functions ϕ, ψ and f with |q| < 1 are classical:

∞

P

ϕ(q) := f (q, q) =

2

n=−∞

ψ(q) := f (q, q 3 ) =

∞

P

q n = (−q; q 2 )2∞ (q 2 ; q 2 )∞ ,

q n(n+1)/2 =

n=0

f (−q) := f (−q, −q 2 ) =

∞

P

n=−∞

(q 2 ; q 2 )∞

,

(q; q 2 )∞

(−1)n q n(3n−1)/2 = (q; q)∞ .

The ordinary or Gaussian hypergeometric function is defined by

2 F1 (a, b; c; z)

:=

∞ (a) (b)

P

n

n n

z ,

n=0 (c)n n!

0 ≤ |z| < 1,

2010 Mathematics Subject Classification: 33D10, 11A55, 11F27

Keywords and phrases: Modular equations; theta-functions

283

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.3)

284

M.S. Mahadeva Naika, S. Chandankumar, M. Harish

where a, b, c are complex numbers such that c 6= 0, −1, −2, . . . , and

(a)0 = 1, (a)n = a(a + 1) · · · (a + n − 1) for any positive integer n.

Now we recall the notion of modular equation. Let K(k) be the complete elliptic

integral of the first kind of modulus k. Recall that

¡ 1 ¢2

Z π/2

∞

dφ

π P

π

2 n 2n

p

K(k) :=

=

k = ϕ2 (q), (0 < k < 1), (1.4)

2 n=0 (n!)2

2

0

1 − k 2 sin2 φ

√

and set K 0 = K(k 0 ), where k 0 = 1 − k 2 is the so called complementary modulus

0

of k. It is classical to set q(k) = e−πK(k )/K(k) so that q is one-to-one, increasing

from 0 to 1.

In the same manner introduce L1 = K(`1 ), L01 = K(`01 ) and suppose that the

following equality

K0

L0

n1

= 1

(1.5)

K

L1

holds for some positive integer n1 . Then a modular equation of degree n1 is an

algebraic relation between the moduli k and `1 which is induced by (1.5). Following

Ramanujan, set α = k 2 and β = `21 . Then we say that β is of degree n1 over α.

The multiplier m is defined by

m=

K

ϕ2 (q)

= 2 n1 ,

L1

ϕ (q )

(1.6)

0

for q = e−πK(k )/K(k) .

of the

Let K, K 0 , L1 , L01 , L2 , L02 , L3 and L03 denote complete elliptic integrals

√

√ √ √

first kind corresponding, in pairs, to the moduli α, β, γ and δ, and their

complementary moduli, respectively. Let n1 , n2 and n3 be positive integers such

that n3 = n1 n2 . Suppose that the equalities

n1

K0

L0

K0

L0

K0

L0

= 1 , n2

= 2 and n3

= 3

K

L1

K

L2

K

L3

(1.7)

√ √

hold. Then

√ a “mixed” modular equation is a relation between the moduli α, β,

√

γ and δ that is induced by (1.7). We say that β, γ and δ are of degrees n1 ,

n2 and n3 respectively over α. The multipliers m = K/L1 and m0 = L2 /L3 are

algebraic relation involving α, β, γ and δ.

At scattered places of his second notebook [5], Ramanujan recorded a total of

nine P –Q mixed modular relations of degrees 1, 3, 5 and 15. For example, if

P :=

f (−q 3 )f (−q 5 )

q 1/3 f (−q)f (−q 15 )

then

and Q :=

f (−q 6 )f (−q 10 )

q 2/3 f (−q 2 )f (−q 30 )

,

³ Q ´3 ³ P ´3

1

=

+

+ 4.

(1.8)

PQ

P

Q

The proofs of these nine P –Q mixed modular relations can be found in the book

by Berndt [2, pp. 214–235]. In [3,4], S. Bhargava, C. Adiga and M. S. Mahadeva

PQ +

Mixed modular equations involving Ramanujan’s theta-functions

285

Naika have established several new P –Q mixed modular relations with four moduli. These mixed modular equations are employed to evaluate explicit evaluations

of Ramanujan-Weber class invariants, ratios of Ramanujan’s theta functions and

several continued fractions.

Motivated by all these works, in this article, we establish several new mixed

modular equations involving Ramanujan’s theta-functions.

In Section 2, we collect some identities which are useful in proofs of our main

results. In Section 3, we establish several new P –Q mixed modular equations akin

to those recorded by Ramanujan in his notebooks involving his theta-functions ϕ(q)

and ψ(q).

2. Preliminary results

In this section, we collect some identities which are useful in establishing our

main results.

Lemma 2.1. [1, Ch. 16, Entry 24 (ii), p. 39] We have

f 3 (−q) = ϕ2 (−q)ψ(q).

(2.1)

Lemma 2.2. [1, Ch. 16, Entry 24 (iv), p. 39] We have

f 3 (−q 2 ) = ϕ(−q)ψ 2 (q).

(2.2)

Lemma 2.3. [1, Ch. 17, Entry 10 (i) and Entry 11(ii), pp. 122–123] For

0 < α < 1, we have

√

ϕ(q) = z,

(2.3)

√ 1/8

√

1/8

2q ψ(−q) = z{α(1 − α)} .

(2.4)

Lemma 2.4. [1, Ch. 20, Entry 3 (xii), (xiii), pp. 352–353] Let α, β and γ be of

the first, third and ninth degrees respectively. Let m denote the multiplier relating

α, β and m0 be the multiplier relating γ, δ. Then

³ β 2 ´1/4 ³ (1 − β)2 ´1/4 ³

´1/4

β 2 (1 − β)2

m

+

−

= −3 0 ,

αγ

(1 − α)(1 − γ)

αγ(1 − α)(1 − γ)

m

(2.5)

³ αγ ´1/4 ³ (1 − α)(1 − γ) ´1/4 ³ αγ(1 − α)(1 − γ) ´1/4

0

m

+

−

=

.

(2.6)

β2

(1 − β)2

β 2 (1 − β)2

m

Lemma 2.5. [1, Ch. 20, Entry 11 (viii), (ix), p. 384] Let α, β, γ and δ be of

the first, third, fifth and fifteenth degrees respectively. Let m denote the multiplier

286

M.S. Mahadeva Naika, S. Chandankumar, M. Harish

relating α and β and m0 be the multiplier relating γ and δ. Then

³ αδ ´1/8 ³ (1 − α)(1 − δ) ´1/8 ³ αδ(1 − α)(1 − δ) ´1/8 r m0

+

−

=

,

βγ

(1 − β)(1 − γ)

βγ(1 − β)(1 − γ)

m

(2.7)

r

³ βγ ´1/8 ³ (1 − β)(1 − γ) ´1/8 ³ βγ(1 − β)(1 − γ) ´1/8

m

+

−

=−

.

αδ

(1 − α)(1 − δ)

αδ(1 − α)(1 − δ)

m0

(2.8)

q 1/6 f (−q)f (−q 9 )

q 1/3 f (−q 2 )f (−q 18 )

and

M

:=

, then

f 2 (−q 3 )

f 2 (−q 6 )

h L3

L9

M9

M3 i

1

+ 9 + 12

+ 3 + 27L3 M 3 − 3 3 = 0.

(2.9)

9

3

M

L

M

L

L M

Lemma 2.6. [3] If L :=

Lemma 2.7. [2,3] If L :=

then

L3 M 3 +

1

L3 M 3

q 2/3 f (−q 2 )f (−q 30 )

q 1/3 f (−q)f (−q 15 )

and

M

:=

,

f (−q 3 )f (−q 5 )

f (−q 6 )f (−q 10 )

h L3

h L6

M3 i

M 6 i h L9

M9 i

+ 3 − 12

+ 6 −

+ 9 = 76. (2.10)

3

6

9

M

L

M

L

M

L

− 48

3. New mixed modular equations

In this section, we establish several new mixed modular equations involving

Ramanujan’s theta-functions ϕ(q) and ψ(q).

√

qψ(−q)ψ(−q 9 )

ϕ(q)ϕ(q 9 )

Theorem 3.1. If L :=

and

M

:=

, then

ϕ2 (q 3 )

ψ 2 (−q 3 )

L2 =

M2 + 1

.

1 − 3M 2

Proof. The equations (2.5) and (2.6) can be rewritten as

m ³ αγ(1 − α)(1 − γ) ´1/4

m0 ³ αγ(1 − α)(1 − γ) ´1/4

+

=

1

−

3

.

m

β 2 (1 − β)2

m0

β 2 (1 − β)2

(3.1)

(3.2)

Transforming the above equation (3.2) by using the equations (2.3) and (2.4), we

arrive at the equation (3.1).

√

qψ(−q)ψ(−q 9 )

qψ(−q 2 )ψ(−q 18 )

Theorem 3.2. If P :=

and

Q

:=

, then

ψ 2 (−q 3 )

ψ 2 (−q 6 )

P2

Q2 ³ P 2

Q2 ´2

+ 2+

+ 2

2

2

Q

P

Q

P

³

1

3P

3Q P 3

Q3 ´

1 ´³

3P Q −

+

+

+ 3 + 3 + 14. (3.3)

= 3P Q −

PQ

PQ

Q

P

Q

P

Mixed modular equations involving Ramanujan’s theta-functions

287

Proof. Using the equation (2.2) in the equation (2.9), we deduce

a3 P 12 − aP 4 bQ4 + 27a2 P 8 b2 Q8 + 12a2 P 8 bQ4 + 12aP 4 b2 Q8 + b3 Q12 = 0,

2

2

(3.4)

9

ϕ (q)ϕ (q )

and b := a(q 2 ).

ϕ4 (q 3 )

Using the equation (3.1), we have

where a := a(q) :=

a :=

P2 + 1

Q2 + 1

and b :=

.

2

1 − 3P

1 − 3Q2

(3.5)

Employing the equations (3.5) in the equation (3.4), we find

A(P, Q)B(P, Q) = 0,

(3.6)

where

¡

A(P, Q) := − 2P 2 Q4 − 13P 6 Q2 + 25P 6 Q4 + 9P 4 Q4 − 13P 2 Q6 − 16P 8 Q2

+ 39P 8 Q4 − 6P 10 Q2 − 27P 6 Q6 − 18P 8 Q6 + 25P 4 Q6 − 16P 2 Q8 + 39P 4 Q8

+ 9P 10 Q4 − 18P 6 Q8 − 27P 8 Q8 − 6P 2 Q10 + 9P 4 Q10 + P 2 Q2 + P 6 + Q6

¢

+ P 10 + 2P 8 + 2Q8 + Q10 − 2P 4 Q2

and

¡

B(P, Q) := − P 8 + 3P 8 Q2 − P 6 Q2 − P 6 + 9P 6 Q4 + 9P 6 Q6 − Q6 + 9P 4 Q6

¢

+ 6P 4 Q4 − 3P 4 Q2 + 3P 2 Q8 − P 2 Q6 − 3P 2 Q4 + P 2 Q2 − Q8 .

Expanding in powers of q, the first and second factor of the equation (3.6), one gets

respectively,

¡

¢

A(P, Q) = −q 3 − 1 − q + q 2 + 4q 3 − 10q 4 − 4q 5 + 37q 6 − 28q 7 − 48q 8 + · · ·

and

¡

¢

B(P, Q) = q 5 4 − 12q − 28q 2 + 144q 3 − 32q 4 − 764q 5 + 1424q 6 + 1400q 7 + · · · .

As q → 0, the factor q −3 B(P, Q) of the equation (3.6) vanishes whereas the other

factor q −3 A(P, Q) do not vanish. Hence, we arrive at the equation (3.3) for q ∈

(0, 1). By analytic continuation the equation (3.3) is true for |q| < 1.

√

qψ(q)ψ(q 9 )

qψ(q 2 )ψ(q 18 )

Theorem 3.3. If P :=

and

Q

:=

, then

ψ 2 (q 3 )

ψ 2 (q 6 )

Q2

1

P2

+ 2 = 4 − 3P 2 + 2 .

2

Q

P

P

(3.7)

Proof. Using the equation (2.1) in the equation (2.9), we deduce

27a2 P 4 b2 Q4 + a3 P 6 + 12a2 P 4 bQ2 + 12aP 2 b2 Q4 + b3 Q6 = aP 2 bQ2 ,

where a := a(q) =

ϕ2 (−q)ϕ2 (−q 9 )

and b := a(q 2 ).

ϕ4 (−q 3 )

(3.8)

288

M.S. Mahadeva Naika, S. Chandankumar, M. Harish

Using the equation (3.1) after changing q by −q, we find

a=

1 − P2

1 − Q2

and

b

=

.

1 + 3P 2

1 + 3Q2

(3.9)

Employing the equations (3.9) in the equation (3.8), we find

¡ 2 2

¢¡

¢

3P Q + P 2 − 1 + Q2 3P 4 Q2 + P 4 − 4P 2 Q2 − Q2 + Q4

¡

1 − 2P 2 − 2Q2 + P 4 + 44P 2 Q2 + 6P 4 Q2 + 9P 4 Q4 + 16P Q

´

+ 48P 3 Q3 + 6P 2 Q4 + Q4 = 0.

(3.10)

Expanding in powers of q, factors of the equation (3.10) becomes respectively,

¡

¢

− 1 + q + 3q 2 + 2q 3 + 2q 4 − 2q 5 − q 6 − 8q 7 − 24q 8 + · · · ,

¡

¢

q 4 − 4 − 8q − 8q 2 + 12q 3 + 52q 4 + 24q 5 − 76q 6 − 120q 7 + 32q 8 + · · ·

and

¡

¢

1 − 2q − 5q 2 + 50q 3 + 105q 4 + 68q 5 − 82q 6 − 374q 7 − 362q 8 + · · · .

As q → 0, the second factor of the equation (3.10) vanishes whereas the other

factors do not vanish. Hence, we arrive at the equation (3.7) for q ∈ (0, 1). By

analytic continuation the equation (3.7) is true for |q| < 1.

Theorem 3.4. If P :=

ϕ(−q)ϕ(−q 9 )

ϕ(−q 2 )ϕ(−q 18 )

and Q :=

, then

2

3

ϕ (−q )

ϕ2 (−q 6 )

Q2

1

P2

+ 2 = 4 − 3Q2 + 2 .

2

Q

P

Q

(3.11)

Proof. The proof of the equation (3.11) is similar to the proof of the equation

(3.7). Hence, we omit the details.

ϕ(−q)ϕ(−q 9 )

ϕ(−q 4 )ϕ(−q 36 )

and

Q

:=

, then

ϕ2 (−q 3 )

ϕ2 (−q 12 )

³P4

³P2

³P2

´

Q4 ´

Q2 ´

3Q4 ´ ³ 1

2 4

+

+

8

+

−

3

−

−

−

27P

Q

Q4

P4

Q2

P2

Q4

P2

P 2 Q4

³ 1

´

³ 1

´

³

1 ´

− 8 2 2 + 9P 2 Q2 − 12 2 − 3P 2 + 3 9Q4 + 4 = 24. (3.12)

P Q

P

Q

Theorem 3.5. If P :=

Proof. Using the equation (2.9) along with the equations (2.1) and (2.2), we

deduce

27P 4 u4 Q8 v 2 + 12P 4 u4 Q4 v + 12Q8 v 2 P 2 u2 + P 6 u6 + Q12 v 3 = P 2 u2 Q4 v,

where u :=

qψ 2 (q)ψ 2 (q 9 )

and v := u(q 4 ).

ψ 4 (q 3 )

(3.13)

Mixed modular equations involving Ramanujan’s theta-functions

289

Invoking the equation (3.1), we find

1 − P2

1 − Q2

u :=

and

v

:=

.

(3.14)

3P 2 + 1

3Q2 + 1

Using the equations (3.14) in the equation (3.13), we find

¡ 2 4

¢¡

3Q P + P 4 − 2Q2 P 2 − P 2 + 3P 2 Q4 + Q4 − Q2 3Q2 P 2 + P 2 − 1

¢¡

¢¡

+ 4QP + Q2 3Q2 P 2 + P 2 − 1 − 4QP + Q2 P 8 + 27P 6 Q8 − 72P 6 Q6

+ 36P 6 Q4 + 8P 6 Q2 − 3P 6 + 27P 4 Q8 − 24P 4 Q4 + 3P 4 + 9P 2 Q8

¢

+ 8P 2 Q6 − 12P 2 Q4 − 8Q2 P 2 − P 2 + Q8 = 0.

(3.15)

As q → 0, the last factor of the equation (3.15) vanishes whereas the other factors

do not vanish. Hence, we arrive at the equation (3.12) for q ∈ (0, 1). By analytic

continuation the equation (3.12) is true for |q| < 1.

ϕ(−q)ϕ(−q 9 )

ϕ(q)ϕ(q 9 )

and

Q

:=

, then

ϕ2 (−q 3 )

ϕ2 (q 3 )

³P

Q´ ³

1 ´

+

+ 3P Q −

− 4 = 0.

Q P

PQ

Theorem 3.6. If P :=

(3.16)

Proof. Using the equation (2.9) along with the equations (2.1) and (2.2), we

deduce

27P 8 u2 Q4 v 4 + P 12 u3 + 12P 8 u2 Q2 v 2 + 12P 4 uQ4 v 4 + Q6 v 6 = P 4 uQ2 v 2 , (3.17)

qψ 2 (q)ψ 2 (q 9 )

qψ 2 (−q)ψ 2 (−q 9 )

where u :=

and

v

:=

.

ψ 4 (q 3 )

ψ 4 (−q 3 )

Invoking the equation (3.1), we find

Q2 − 1

1 − P2

and v :=

.

(3.18)

u :=

2

3P + 1

3Q2 + 1

Using the equations (3.18) in the equation (3.17), we find

¡ 2 2

¢¡

¢¡

3P Q + Q2 − 1 + 4P Q + P 2 3P 2 Q2 + Q2 − 1 − 4P Q + P 2 3P 2 Q4

¢¡

+ Q4 − Q2 − 2P 2 Q2 − P 2 + 3P 4 Q2 + P 4 27P 8 Q6 + 27P 8 Q4 + 9P 8 Q2

+ P 8 − 72P 6 Q6 + 8P 6 Q2 + 36P 4 Q6 − 24P 4 Q4 − 12P 4 Q2 + 8P 2 Q6

¢

− 8P 2 Q2 + Q8 − 3Q6 + 3Q4 − Q2 = 0.

(3.19)

As q → 0, the second factor of the equation (3.19) vanishes whereas the other

factors do not vanish. Hence, we arrive at the equation (3.16) for q ∈ (0, 1). By

analytic continuation the equation (3.16) is true for |q| < 1.

√

qψ(q)ψ(q 9 )

q 2 ψ(q 4 )ψ(q 36 )

Theorem 3.7. If P :=

and

Q

:=

, then

ψ 2 (q 3 )

ψ 2 (q 12 )

³P4

³P2

³

³ 3P 4

Q4 ´

Q2 ´

1 ´

Q2 ´

2 2 2

+

+

8

+

−

8

3

P

Q

+

+

3

−

Q4

P4

Q2

P2

P 2 Q2

Q2

P4

´

³

´

³

´

³

1

1

1

+ 27P 4 Q2 − 4 2 + 3 9P 4 + 4 + 12 3Q2 − 2 − 24 = 0. (3.20)

P Q

P

Q

290

M.S. Mahadeva Naika, S. Chandankumar, M. Harish

Proof. The proof of the equation (3.20) is similar to the proof of the equation

(3.12). Hence, we omit the details.

√

qψ(q)ψ(q 9 )

qψ(−q)ψ(−q 9 )

and

Q

:=

, then

Theorem 3.8. If P :=

ψ 2 (q 3 )

ψ 2 (−q 3 )

³P2

Q2 ´ ³

1 ´³ P

Q´

+

−

3P

Q

+

−

+ 2 = 0.

(3.21)

Q2

P2

PQ Q P

√

Proof. The proof of the equation (3.21) is similar to the proof of the equation

(3.16). Hence, we omit the details.

Theorem 3.9. If L :=

ϕ(q 3 )ϕ(q 5 )

ψ(−q 3 )ψ(−q 5 )

and M :=

, then

15

ϕ(q)ϕ(q )

qψ(−q)ψ(−q 15 )

M=

1+L

.

1−L

Proof. The equations (2.7) and (2.8) can be rewritten as

r ³

r

m αδ(1 − α)(1 − δ) ´1/8

m

m ³ αδ(1 − α)(1 − δ) ´1/8

1+

=

−

.

m0 βγ(1 − β)(1 − γ)

m0

m0 βγ(1 − β)(1 − γ)

(3.22)

(3.23)

Transforming the above equation (3.23) by using the equations (2.3) and (2.4), we

arrive at equation (3.22).

ψ(−q 3 )ψ(−q 5 )

ψ(−q 6 )ψ(−q 10 )

and Q := 2

, then

15

qψ(−q)ψ(−q )

q ψ(−q 2 )ψ(−q 30 )

³P2

Q2 ´ ³ P

Q´ ³

1 ´

+

+

+

−

P

Q

+

Q2

P2

Q P

PQ

s

s

r

r ´

´³

³p

1

P3

Q3

P

Q

PQ − √

+

+

+

+

= 0. (3.24)

3

3

Q

P

Q

P

PQ

Theorem 3.10. If P :=

Proof. Using the equation (2.2) in the equation (2.10), we find

2

a P 4 b2 Q4 + a4 P 8 b4 Q8 − a6 P 12 − 48a4 P 8 b2 Q4 − 12a5 P 10 bQ2

− 48a2 P 4 b4 Q8 − 76a3 P 6 b3 Q6 − b6 Q12 − 12b5 Q10 aP 2 = 0,

(3.25)

ϕ(q 3 )ϕ(q 5 )

and b := a(q 2 ).

ϕ(q)ϕ(q 15 )

Using the equation (3.22), we have

where a := a(q) :=

a := a(q) :=

P −1

Q−1

and b := b(q) :=

.

P +1

Q+1

(3.26)

291

Mixed modular equations involving Ramanujan’s theta-functions

Employing the equations (3.26) in the equation (3.25), we find

¡

¢¡

¢¡

P Q + P − 1 + Q P 2 − P − 2P Q + P Q2 + Q2 P 2 Q + P 2 − Q

¢¡

− 2P Q + Q2 12P 4 Q4 − P 2 Q2 − 5P 4 Q3 − 5P 4 Q2 − 5P 3 Q4 − P 3 Q3

− P 3 Q2 − 5P 2 Q4 − P 2 Q3 − P 6 − Q6 − 3P 8 − 3Q8 + 3P 6 Q2 + 7P 5 Q2

− 3P 6 Q + 3P 2 Q6 + 7P 2 Q5 − 3P Q6 − 7P 4 Q6 − 2P 4 Q5 + 5P 3 Q6

+ 7P 3 Q5 − 12P 5 Q5 − 2P 5 Q4 + 7P 5 Q3 − 7P 6 Q4 + 5P 6 Q3 + P 6 Q6

− 5P 6 Q5 − 5P 5 Q6 + P 7 Q7 − P 7 Q6 + 5P 7 Q5 − P 6 Q7 + 5P 5 Q7 + 7P 7 Q4

+ 7P 4 Q7 + 3Q7 + Q9 + 3P 7 + P 9 + 3P 9 Q2 + P 9 Q3 − 3P 3 Q8 − 3P 3 Q7

+ P 3 Q9 + 3P 9 Q − 9P 8 Q2 + 3P 7 Q2 − 9P 8 Q + 9P 7 Q − 3P 8 Q3

− 3P 7 Q3 + 3Q9 P 2 − 9Q8 P 2 + 3Q7 P 2 + 9Q7 P − 9Q8 P + 3P Q9

¡ 4

P + Q4 − P 2 Q − P Q2 − P Q + P 4 Q − P 3 Q3 + P 3 Q2 + P 3 Q

¢

+ P 2 Q3 + P Q4 + P Q3 − P 3 − Q3 = 0.

¢

(3.27)

As q → 0, the last factor of the equation (3.27) vanishes whereas the other factors

do not vanish. Hence, we arrive at the equation (3.24) for q ∈ (0, 1). By analytic

continuation the equation (3.24) is true for |q| < 1.

ψ(q 3 )ψ(q 5 )

ψ(q 6 )ψ(q 10 )

and

Q

:=

, then

qψ(q)ψ(q 15 )

q 2 ψ(q 2 )ψ(q 30 )

³P

Q´ ³

1´

+

= P−

+ 2.

Q P

P

Theorem 3.11. If P :=

(3.28)

Proof. Using the equation (2.1) in the equation (2.10), we deduce

2

a P 2 b2 Q2 + a4 P 4 b4 Q4 − a6 P 6 − 48a4 P 4 b2 Q2 − 12a5 P 5 bQ

− 48a2 P 2 b4 Q4 − 76a3 P 3 b3 Q3 − b6 Q6 − 12b5 Q5 aP = 0,

(3.29)

ϕ(−q 3 )ϕ(−q 5 )

and b := a(q 2 ).

ϕ(−q)ϕ(−q 15 )

Changing q to −q in the equation (3.22), we find

where a := a(q) :=

a :=

1+P

1+Q

and b :=

.

P −1

Q−1

(3.30)

Using the equations (3.30) in the equation (3.29), we find

¡

¢¡

¢¡

− P + P Q − 1 − Q − P 2 + P 2 Q + 2P Q − Q − Q2 P 2 + P − 2P Q

¢¡

+ Q2 − P Q2 − P 4 − P 3 − Q3 − P Q2 − P Q3 + P Q4 − P 2 Q + P 2 Q3

¢¡

− P 3 Q + P 3 Q2 + P 3 Q3 + P 4 Q − Q4 + P Q − 3P 8 − P 6 − 3P 7 − P 9

− P 2 Q2 + P 2 Q3 − 5P 2 Q4 + P 3 Q2 − P 3 Q3 + 5P 3 Q4 − 5P 4 Q2 + 5P 4 Q3

+ 12P 4 Q4 + 3QP 6 + 9QP 7 + 9QP 8 + 7Q3 P 5 − 5Q3 P 6 − 3Q3 P 7 + 3Q3 P 8

292

M.S. Mahadeva Naika, S. Chandankumar, M. Harish

− 7P 5 Q2 + 3P 6 Q2 − 3P 7 Q2 − 9P 8 Q2 − 3P 9 Q2 + P 9 Q3 + 2P 5 Q4 − 7P 6 Q4

− 7P 7 Q4 + 3P 9 Q + 2P 4 Q5 − 7P 4 Q6 − 7P 4 Q7 + 5P 6 Q5 + P 6 Q6 + P 6 Q7

− 12P 5 Q5 + 5P 5 Q6 + 5P 5 Q7 + 5P 7 Q5 + P 7 Q6 + P 7 Q7 + 3P Q6 + 9P Q7

+ 9P Q8 + 7P 3 Q5 − 5P 3 Q6 − 3P 3 Q7 + 3P 3 Q8 + 3P Q9 − 7P 2 Q5 + 3P 2 Q6

¢

− 3P 2 Q7 − 9P 2 Q8 − 3P 2 Q9 + P 3 Q9 − 3Q8 − Q6 − 3Q7 − Q9 = 0.

(3.31)

As q → 0, the second factor of the equation (3.31) vanishes whereas the other

factors do not vanish. Hence, we arrive at the equation (3.28) for q ∈ (0, 1). By

analytic continuation the equation (3.28) is true for |q| < 1.

ϕ(−q 6 )ϕ(−q 10 )

ϕ(−q 3 )ϕ(−q 5 )

and Q :=

, then

15

ϕ(−q)ϕ(−q )

ϕ(−q 2 )ϕ(−q 30 )

³P

Q´ ³

1´

+

= Q−

+ 2.

(3.32)

Q P

Q

Theorem 3.12. If P :=

Proof. The proof of the equation (3.32) is similar to the proof of the equation

(3.28). Hence, we omit the details.

ϕ(−q 3 )ϕ(−q 5 )

ϕ(−q 12 )ϕ(−q 20 )

and Q :=

, then

15

ϕ(−q)ϕ(−q )

ϕ(−q 4 )ϕ(−q 60 )

³P2

³

³

³P

Q2 ´

1 ´

1 ´

Q2 ´

2

+

+

3

Q

+

−

4

P

Q

+

+

3

−

Q2

P2

Q2

PQ

Q2

P

³

´

³

´

³

1

1

1´

− P Q2 +

−

2

P

−

+

4

Q

−

= 0. (3.33)

P Q2

P

Q

Theorem 3.13. If P :=

Proof. Using the equations (2.1) and (2.2) in the equation (2.10), we deduce

48Q2 b2 P 4 a4 − Q4 b4 P 4 a4 − Q2 b2 P 2 a2 + 48Q4 b4 P 2 a2 + P 6 a6

+ 76Q3 b3 P 3 a3 + 12QbP 5 a5 + Q6 b6 + 12Q5 b5 P a = 0,

(3.34)

ψ(q 3 )ψ(q 5 )

and b := a(q 4 ).

ψ(q)ψ(q 15 )

Changing q to −q in the equation (3.22), we find

where a := a(q) :=

a :=

1+P

1+Q

and b :=

.

P −1

Q−1

Employing the equations (3.35) in the equation (3.34), we deduce

¡ 2 2

¢¡

Q P − 2QP 2 + P 2 + 2P + 1 − 4QP + 2Q − 2Q2 P + Q2 QP 2 − P 2

¢¡

− P − Q + Q2 P − Q2 3Q8 − 6P 4 − 15P 7 − 6P 8 + 45Q8 P 4 + 3QP 3

+ 18QP 4 + 45QP 5 + 60QP 6 + 45QP 7 + 18QP 8 − Q2 P + 8Q2 P 2

+ 10Q2 P 3 − 28Q2 P 4 − 68Q2 P 5 − 64Q2 P 6 − 34Q2 P 7 − 12Q2 P 8

(3.35)

Mixed modular equations involving Ramanujan’s theta-functions

293

+ Q3 P − 8Q3 P 2 − 12Q3 P 3 + 16Q3 P 4 + 38Q3 P 5 + 24Q3 P 6 + 4Q3 P 7

− 5Q4 P + 3Q4 P 2 − 9Q4 P 3 − 13Q4 P 4 + 33Q4 P 5 + 17Q4 P 6 − 19Q4 P 7

− 7Q4 P 8 − 7Q5 P + 19Q5 P 2 + 17Q5 P 3 − 33Q5 P 4 − 13Q5 P 5 + 9Q5 P 6

+ 3Q5 P 7 + 5Q5 P 8 + 4Q6 P 2 − 24Q6 P 3 + 38Q6 P 4 − 16Q6 P 5 − 12Q6 P 6

+ 8Q6 P 7 + Q6 P 8 + 3QP 9 − 3Q2 P 9 + Q3 P 9 + 3Q8 P 6 − 18Q8 P 5

+ 15Q9 P 4 − 6Q9 P 5 + Q9 P 6 + Q6 − P 3 − 20P 6 − 15P 5 − P 9 + 45Q8 P 2

+ 34Q7 P 2 + 15Q9 P 2 − 64Q7 P 3 + 68Q7 P 4 − 28Q7 P 5 − 10Q7 P 6 + 8Q7 P 7

¢

+ Q7 P 8 − 60Q8 P 3 − 20Q9 P 3 + 3Q7 + Q9 − 6Q9 P − 18Q8 P − 12Q7 P

¡ 4

P + Q4 + 3P 2 + P − 4QP − 4QP 2 + 2Q2 P − 2Q2 P 3 + 4Q3 P 2

¢

− 4Q3 P 3 − 3Q4 P + 3Q4 P 2 − Q4 P 3 + 3P 3 = 0.

(3.36)

As q → 0, the last factor of the equation (3.36) vanishes whereas the other factors

do not vanish. Hence, we arrive at the equation (3.33) for q ∈ (0, 1). By analytic

continuation the equation (3.33) is true for |q| < 1.

Acknowledgement. The authors are grateful to the referee for his/her valuable remarks and suggestions which considerably improved the quality of the paper.

REFERENCES

[1] B. C. Berndt, Ramanujan’s Notebooks, Part III, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1991.

[2] B. C. Berndt, Ramanujan’s Notebooks, Part IV, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1994.

[3] S. Bhargava, C. Adiga, M.S. Mahadeva Naika, A new class of modular equations in Ramanujan’s alternative theory of elliptic function of signature 4 and some new P –Q eta-function

identities, Indian J. Math. 45 (1) (2003), 23–39.

[4] S. Bhargava,C. Adiga, M.S. Mahadeva Naika, A new class of modular equations akin to Ramanujan’s P –Q eta-function identities and some evaluations therefrom, Adv. Stud. Contemp.

Math. 5 (1) (2002), 37–48.

[5] S. Ramanujan, Notebooks (2 volumes), Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Bombay,

1957.

(received 14.12.2012; in revised form 24.06.2013; available online 10.09.2013)

M. S. Mahadeva Naika, M. Harish, Department of Mathematics, Bangalore University, Central

College Campus, Bengaluru-560 001, Karnataka, India

E-mail: msmnaika@rediffmail.com, numharish@gmail.com

S. Chandankumar, Department of Mathematics, Acharya Institute of Graduate Studies, Soldevanahalli, Hesarghatta Main Road, Bengaluru-560 107, Karnataka, India

E-mail: chandan.s17@gmail.com