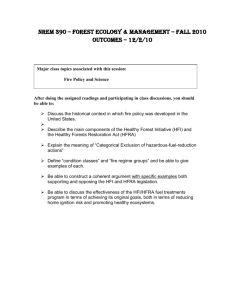

The Healthy Forests

advertisement