How to Lie with Statistics, Chapters 8-10: Daniel Huff

advertisement

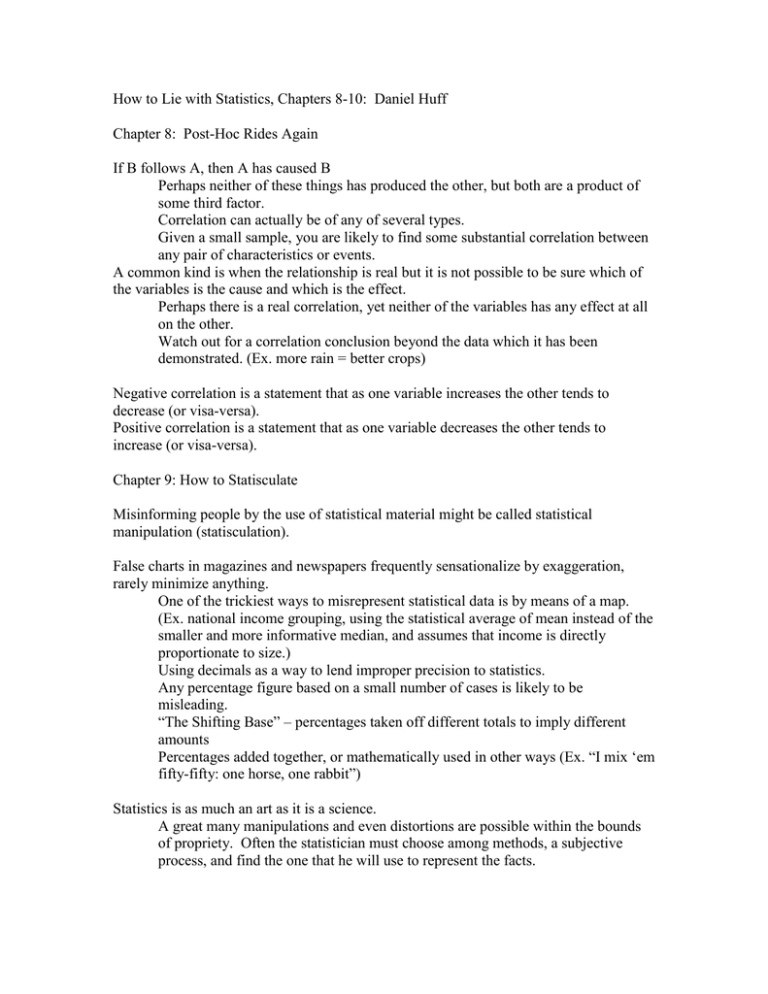

How to Lie with Statistics, Chapters 8-10: Daniel Huff Chapter 8: Post-Hoc Rides Again If B follows A, then A has caused B Perhaps neither of these things has produced the other, but both are a product of some third factor. Correlation can actually be of any of several types. Given a small sample, you are likely to find some substantial correlation between any pair of characteristics or events. A common kind is when the relationship is real but it is not possible to be sure which of the variables is the cause and which is the effect. Perhaps there is a real correlation, yet neither of the variables has any effect at all on the other. Watch out for a correlation conclusion beyond the data which it has been demonstrated. (Ex. more rain = better crops) Negative correlation is a statement that as one variable increases the other tends to decrease (or visa-versa). Positive correlation is a statement that as one variable decreases the other tends to increase (or visa-versa). Chapter 9: How to Statisculate Misinforming people by the use of statistical material might be called statistical manipulation (statisculation). False charts in magazines and newspapers frequently sensationalize by exaggeration, rarely minimize anything. One of the trickiest ways to misrepresent statistical data is by means of a map. (Ex. national income grouping, using the statistical average of mean instead of the smaller and more informative median, and assumes that income is directly proportionate to size.) Using decimals as a way to lend improper precision to statistics. Any percentage figure based on a small number of cases is likely to be misleading. “The Shifting Base” – percentages taken off different totals to imply different amounts Percentages added together, or mathematically used in other ways (Ex. “I mix ‘em fifty-fifty: one horse, one rabbit”) Statistics is as much an art as it is a science. A great many manipulations and even distortions are possible within the bounds of propriety. Often the statistician must choose among methods, a subjective process, and find the one that he will use to represent the facts. This suggests giving statistical material, the facts and figures in newspapers and books, magazines and advertising, a very sharp second look before accepting any of them. Chapter 10: How to Talk Back to a Statistic 1st thing to look for is bias Conscious bias – direct misstatements ambiguous statement selection of favorable data suppression of unfavorable units of measurement maybe be shifted improper measure (trickery covered by the use of the word “average”) Who says so? How does he know? A biased sample, one that has been selected improperly or has selected itself. Reported correlation: is it big enough to mean anything? Are there enough cases to add up to any significance? Look for a measure of reliability (probably error, standard error) What is missing? Look out for “average”: variety unspecified, a matter where mean and median might be expected to differ substantially Percentages are given and raw figures are missing The factor that caused change to occur, implying that some other more desired factor is responsible (Ex. looking at total deaths rather than death rate, don’t forget there are more people now than there used to be) Did somebody change the subject? Watch out for a switch somewhere between the raw figure and the conclusion. Strange things crop out when figures are based on what people say—even about things that seem to be objective facts Does it make sense? Often cuts a statistic down to size when the whole idea is based on an unproved assumption Use common sense The trend-to-now may be a fact, but the future trend represents no more than an educated guess