Document 10497944

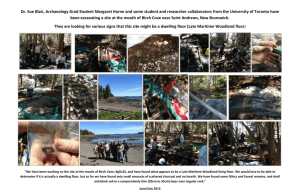

advertisement