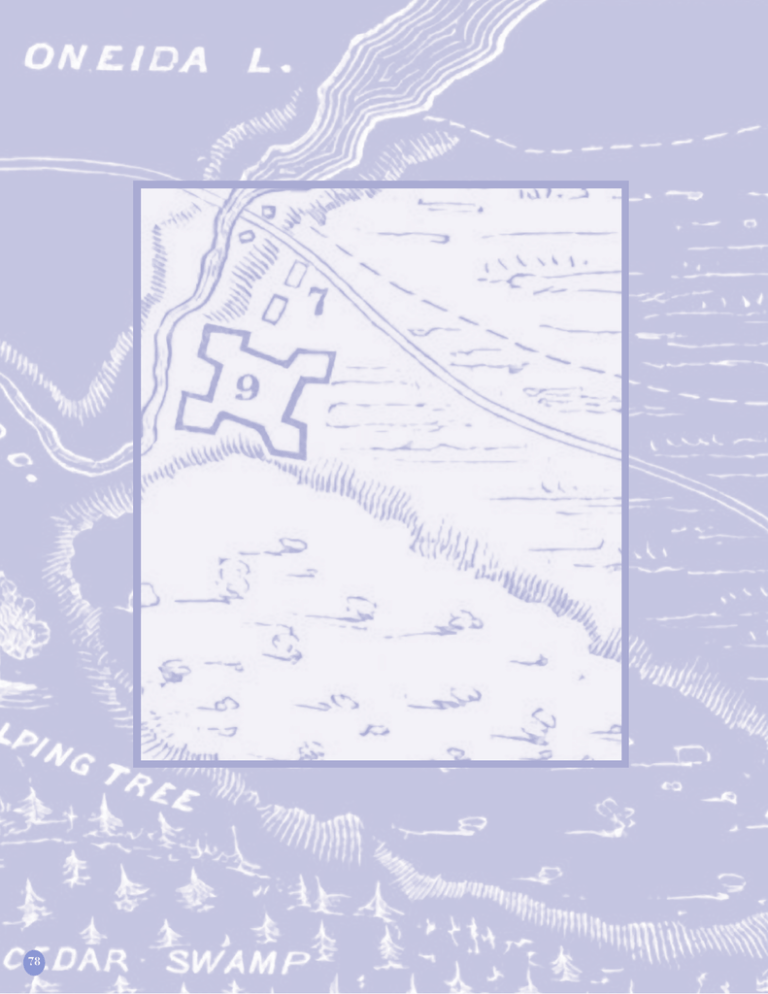

78

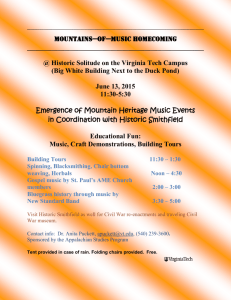

advertisement