:INDIA :I N D I A CONNECTING CITIES

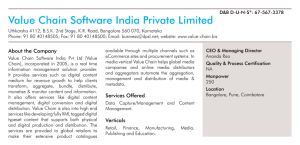

advertisement