NEGOTIATION AS A MEANS OF DEVELOPING AND

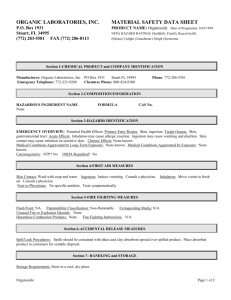

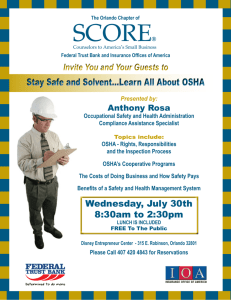

advertisement