Fare Adjustment Strategies for JUNE 2007

advertisement

Fare Adjustment Strategies for

Airline Revenue Management and Reservation Systems

By

Yin Shiang Valenrina Soo

B.B.A. (Hons), NUS Business School

National University of Singapore, 2001

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL

ENGINEERING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE

DEGREE OF

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN TRANSPORTATION

AT THE

INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

MASSACHUSETTS

JUNE 2007

© 2007 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved.

Signature of Author: ................................................

1 ......

Department of Civil and Environmental Enginering

May 10, 2007

Certified by: ..........................................................

Peter P. Belobaba

Principal Research Scientist of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Thesi u ervisor

.... , ... ,..., ..........

Joseph 4At Sussman

ssor of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Thesis Reader

C ertified by: ...........................................................

JR East

.................................................

Daniele Veneziano

Chairman, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students

Accepted by : ................................................

MASSACHUSETTS INSTI

OF TECHNOLOGY

JUN 0 7 2007

LIBRARIES

E

ARKER

Fare Adjustment Strategies for

Airline Revenue Management and Reservation Systems

by

Yin Shiang Valenrina Soo

Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 10, 2007

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Transportation

ABSTRACT

With the growth of Low Cost Carriers (LCC) and their use of simplified fare structures, the

airline industry has seen an increased removal of many fare restrictions, especially in markets

with intense LCC presence. This resulted in "semi-restricted" fare structure where there are

homogenous fare classes that are undifferentiated except by price and also distinct fare classes

which are still differentiated by booking restrictions and advance purchase requirements. In this

new fare environment, the use of traditional Revenue Management (RM) systems, which were

developed based on the assumption of independence of demand of fare classes, tend to lead to a

spiral down effect. Airlines now have to deal with customers who systematically buy the lowest

fare available in the absence of distinctions between the fare classes. This result in fewer

bookings observed in the higher fare classes, leading to lower forecast and less protection of seats

for the higher yield passengers.

This thesis describes Fare Adjustment, a technique developed for network RM systems, which

acts at the booking limit optimizer level as it takes into account the sell-up potential of

passengers (the probability that a passenger is willing to buy a higher-fare ticket if his request is

denied). The goal of this thesis is to provide a more comprehensive investigation into the

effectiveness of fare adjustment as a tool to improve airline revenues in this new environment by

1) extending the investigation of the effectiveness of fare adjustment with standard forecasting to

leg-based RM systems (namely EMSRb and HBP) and also a mixed fare structure where different

fare structures are used for different markets, and 2) looking at the alternative use of fare

adjustment in the reservation system.

Experiments with the Passenger Origin-Destination Simulator demonstrate that RM Fare

Adjustment with standard forecasting can improve an airline's network revenue by 0.8% to 1.3%

over standard revenue management methods. In particular, RM Fare Adjustment reduces the

aggressiveness of path forecasting through the lowering of bid prices as it takes into account the

risk of buying-down. Simulations of Fare Adjustment in the Reservation System also showed

positive results with revenue improvement of about 0.4% to 0.7%.

Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Peter P. Belobaba

Title: Principal Research Scientist of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Thesis Reader: Dr. Joseph M. Sussman

Title: JR East Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, many thanks to Dr. Peter Belobaba for being my academic and

research advisor. He introduced me to the world of revenue management and taught me

all that I needed to know. I appreciate his guidance, mentorship and the opportunities he

has given me during these past 2 years here in MIT.

I must also thank all the airlines in the PODS consortium for making this research

possible through their financial support and continuous feedback. Acknowledgement also

goes to our programmer, Craig Hopperstad, for helping me understand the workings of

the PODS simulator.

As for all my fellow colleagues (past and present) in the MIT International Center for Air

Transportation and my friends in the MST program, thank you for helping me get

through the years. Special thanks to Maital Dar, Thierry Vanhaverbeke and Greg Zerbib

for teaching me the ropes and helping me learn about PODS.

I must also thank all my friends from the MIT Ballroom Dance Team in particular Jing

Wang, Mingzhi Liu and Royson Chong. Without them, my life would have been a lot less

exciting and my drawers would not be filled with so many ribbons and awards.

To my family back home in Singapore, thank you for all that you have done for me. I

would not be who I am today without you guys. Thank you for your unwavering love,

care and concern for me.

To Escamillo, my beloved husband, thank you for your love, understanding and support.

You are always there for me, encouraging me and cheering me on. Now that I am ending

this "Graduate School in MIT" chapter of my life, I look forward to starting a whole new

"Life in NYC" chapter with you. You are the best husband and friend one can ever hope

for. I love you.

And last but not least, I thank God for His love for me. Thanks to Him for giving me the

strength, the courage and faith to carry on even when things sometimes look impossible.

He has been my stronghold and shelter and I thank Him for all the provisions He had

given me and the miracles He had performed in my life.

-5-

-6-

-IMLE OF CONTENTS

Page

LIST OF FIGURES

10

LIST OF TABLES

13

1.

1.1

REVENUE MANAGEMENT

15

1.2

CHANGES IN THE INDUSTRY

17

1.3

NEW / RECENT APPROACHES

18

1.3.1

1.3.2

1.3.3

2.

15

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

18

19

19

Forecasting and Sell-up

Q/Hybrid Forecasting

Fare Adjustment

1.4

OBJECTIVES OF THE THESIS

20

1.5

ORGANIZATION OF THE THESIS

21

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1

23

REVENUE MANAGEMENT

2.1.1

2.1.2

23

25

26

Forecasting

Seat Inventory Control

2.2

LOW COST CARRIERS AND A LESS-RESTRICTED ENVIRONMENT

29

2.3

REVENUE MANAGEMENT TOOLS FOR THE NEW ENVIRONMENT

31

Fare Adjustment

32

33

CHAPTER SUMMARY

35

2.3.1

2.3.2

2.4

Q / Hybrid Forecasting

-7-

3.

CHAPTER THREE: SIMULATION APPROACH TO RM

37

3.1

THE PODS SIMULATION TOOL

37

3.1.1

3.1.2

39

41

3.2

3.3

4.

Passenger Choice Model

PODS Revenue Management Systems

SIMULATION ENVIRONMENT

42

3.2.1

3.2.2

42

44

Network D

Network S

FARE ADJUSTMENT IN REVENUE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

48

3.3.1

3.3.2

3.3.3

FRAT5s

Sell up

Formulation and Parameters in PODS

49

50

52

3.4

FARE ADJUSTMENT IN RESERVATION SYSTEM

56

3.5

CHAPTER SUMMARY

57

CHAPTER FOUR: FARE ADJUSTMENT IN RM SYSTEM

59

4.1

NETWORK D

59

4.1.1

4.1.2

4.1.3

4.1.4

60

61

61

65

4.2

4.3

DAVN

EMSRb with Path Forecasting

EMSRb (Path) with Fare Adjustment

HBP

NETWORK S

67

4.2.1

4.2.2

4.2.3

4.2.4

68

69

70

73

EMSRb with Path Forecasting

Path-based EMSRb with Fare Adjustment

HBP with Fare Adjustment

DAVN with Fare Adjustment

CHAPTER SUMMARY

75

-8-

5.

CHAPTER FIVE: FARE ADJUSTMENT IN RESERVATION SYSTEM

5.1

5.2

Introduction of RES Bid Price to Leg-Based EMSRb

Leg-Based EMSRb with RES Fare Adjustment

Leg-Based HBP with RES Fare Adjustment

77

79

81

83

NETWORK S

5.2.1

5.2.2

Leg-Based EMSRb with RES Fare Adjustment

Leg-Based HBP with RES Fare Adjustment

83

87

CHAPTER SUMMARY

89

CHAPTER SIX: CONCLUSIONS

91

5.3

6.

77

NETWORK D

5.1.1

5.1.2

5.1.3

77

6.1

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

92

6.2

FURTHER RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

94

-9-

T OF FIGURES

Page

1.

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

Figure 1-1

Use of Differential Pricing to Maximize Revenue

2.

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

2-1

2-2

2-3

2-4

3.

Example of a Third Generation System

Spiral-Down Effect

Co-existence of Different Fare Structures in a Network

Using Fare Adjustment to Decouple the Fare Structures

16

24

31

33

34

CHAPTER THREE: SIMULATION APPROACH TO RM

Figure 3-1

Figure 3-2

Figure 3-3

Figure 3-4

Figure 3-5

Figure 3-6

Figure 3-7

Figure 3-8

Figure 3-9

Figure 3-10

Figure 3-11

Figure 3-12

PODS Structure

Network D

ALl's Network

AL2's Network

ALl's Route Network in Network S

AL2's Route Network in Network S

AL3's Route Network in Network S

AL4's Route Network in Network S

FRAT5 Curves in PODS

PODS FA FRAT5s Values with Different Scaling Factors

Probability of Sell-up and FRAT5s

Relationship between Fare, Marginal Revenue and PE Cost

-

10

-

39

43

43

43

45

46

46

47

49

50

51

53

4.

CHAPTER FOUR: FARE ADJUSTMENT IN RM SYSTEM

Figure 4-1

Figure 4-2

Figure 4-3

Figure 4-4

Figure 4-5

Figure 4-6

Figure 4-7

Figure 4-8

Figure 4-9

Figure 4-10

Figure 4-11

Figure 4-12

Figure 4-13

Figure 4-14

Figure 4-15

Figure 4-16

Figure 4-17

Figure 4-18

Figure 4-19

Figure 4-20

Figure 4-21

5.

Base Case Scenario - Fare Class Mix

DAVN with FA in Network D

EMSRb with Path Forecasting in Network D - Fare Class Mix

EMSRb with FA in Network D - Fixed FRAT5s

Airline 1 Fare Class Mix - EMSRb with FA (Fixed FRAT5s)

Load Factor and Yield - EMSRb with FA (Fixed FRAT5s)

Selected Adjusted Fares at FRAT5 C

EMSRb with FA in Network D - Variable FRAT5s

HBP with FA in Network D - Fixed FRAT5s

HBP with FA in Network D - Variable FRAT5s

Airline 1 Fare Class Mix - HBP

Airline l's Loads and Yield - HBP

Base Case Results - Network S

EMSRb with Path Forecasting - Network S

EMSRb with FA in Network S - Variable FRAT5s

HBP with FA in Network S - Variable FRAT5s

Al Spill-in Fare Class Mix - Network D vs. Network S

MSP Fare Class Mix - Path based HBP with FA in Network S

MSP Yield and Load Factor - Path based HBP with FA in Network S

DAVN Results - Network S

DAVN with Fare Adjustment in Network S

59

60

61

62

63

63

64

64

65

66

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

73

74

74

CHAPTER FIVE: FARE ADJUSTMENT IN RESERVATION SYSTEM

Figure 5-1

Figure 5-2

Figure 5-3

Figure 5-4

Figure 5-5

Figure 5-6

Figure 5-7

Figure 5-8

RES Bid Price in Network D

Airline 1 Spill in Fare Class Mix in Network D - RES Bid Price

Local vs. Connect Passengers in Network D - RES Bid Price

EMSRb with RES FA in Network D- FRAT5 psup

LF, Yield & Fare Class Mix - EMSRb with RES FA (FRAT5 psup) in D

EMSRb with RES FA in Network D - Input psup

Al's LF & Yield - EMSRb with RES FA (Input psup) in D

HBP with RES FA in Network D - FRAT5 psup

- 11 -

77

78

78

79

79

80

81

81

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

6.

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure

5-9

5-10

5-11

5-12

5-13

5-14

5-15

5-16

5-17

5-18

HBP with RES FA in Network D - Input psup

Fare Class Comparison - HBP with RES FA in Network D

LF & Yield Comparison - HBP with RES FA in Network D

EMSRb with RES FA in Network S - FRAT5 psup

Al's LF & Yield in S - EMSRb w RES FA in All Mkts (FRAT5 psup)

EMSRb with RES FA in Network S - Input psup

Spill-In Trend - EMSRb with RES FA (All Markets) in Net work D

Spill-In Trend - EMSRb with RES FA (All Markets) in Net work S

HBP with RES FA in Network S - FRAT5 psup

HBP with RES FA in Network S - Input psup

82

83

83

84

85

85

86

87

88

88

CHAPTER SIX: CONCLUSIONS

6-1

6-2

6-3

6-4

Results Summary

Results Summary

Results Summary

Results Summary

- RM Fare Adjustment in Network D

- RM Fare Adjustment in Network S

- RES Fare Adjustment in Network D

- RES Fare Adjustment in Network S

-

12

-

92

92

93

94

T OF TABLES

Page

3.

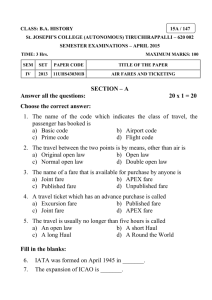

CHAPTER THREE: SIMULATION APPROACH TO RM

Table 3-1

Table 3-2

Table 3-3

Table 3-4

Table 3-5

Table 3-6

Table 3-7

Table 3-8

4.

User-Defined Time Frames in PODS

Network D Fare Structure and Restrictions

Network S O-D Markets and Paths

Fare Structure and Restrictions - LCC Markets

Fare Structure and Restrictions - Non LCC Markets

PSUP for different FA FRAT5s Input

Booking Limits without Fare Adjustment (Path-based EMSRb)

HBP with Fare Adjustment

38

44

47

48

48

52

55

55

CHAFER FOUR: FARE ADJUSTMENT IN RM SYSTEM

Table 4-1 Results of Base Case Scenario

Table 4-2 Results of DAVN in Network D

Table 4-3 Results of EMSRb with Path Forecasting in Network D

Table 4-4 Adjusted Fares with Fixed FRAT5s

Table 4-5 Results of HBP in Network D - Leg Forecasting

Table 4-6 Results of HBP in Network D - Path Forecasting

Table 4-7 Results of HBP in Network S - Leg Forecasting

Table 4-8 Results of HBP in Network S - Path Forecasting

Table 4-9 Al Revenue Improvement over Leg-Based EMSRb in Network D

Table 4-10 Al Revenue Improvement from Fare Adjustment in Network D

Table 4-11 Al Revenue Improvement over Leg-Based EMSRb in Network S

Table 4-12 A l Revenue Improvement from Fare Adjustment in Network S

-

13

-

59

60

61

62

65

65

70

71

75

75

76

76

5.

CHAPTER FIVE: FARE ADJUSTMENT IN RESERVATION SYSTEM

Table 5-1

Table 5-2

Table 5-3

Table 5-4

Al

Al

Al

Al

Revenue

Revenue

Revenue

Revenue

Improvement

Improvement

Improvement

Improvement

over Leg-Based EMSRb in Network D

from RES Fare Adjustment in Network D

over Leg-Based EMSRb in Network S

from RES Fare Adjustment in Network S

-14-

89

89

90

90

1.

INTRODUCTION

Largely pioneered by the passenger airline carriers, revenue management - the integrated

management of price and capacity - has been considered by Robert Crandall, Chairman

and CEO of AMR and American Airlines, to be "the single most important technical

development in transportation management since we entered the era of deregulation in

1979."' Faced with relatively fixed capacity, low marginal sales costs and perishable

inventory, the challenge for an airline is deciding how best to allocate a fixed number of

perishable seats on a distinct and transient flight leg amongst the many possible journeys

which are available for purchase at different prices in order to maximize its revenue.

Thus, revenue management can simply be described as "selling the right seats to the right

customers at the right prices"'. Through a set of practices and policies, airlines make use

of revenue management to guide them in their pricing and seat allocation decisions. In

the following sections of this chapter, we will take a closer look at the history as well as

the reason for revenue management. In addition, we will also present the recent

developments in the airline industry and the new approaches that were developed to meet

these changes.

1.1

REVENUE MANAGEMENT

Before revenue management was born, airlines were mainly using a combination of

forecasting and controlled overbooking in their reservation control, deliberately selling

more seats than what is available to mitigate financial damage by passengers who do not

show up for the flight. This helped them to achieve a moderate degree of success and

almost all quantitative research in reservation control during that period focused on such

controlled overbooking.

In the early 1970s however, BOAC (now known as British Airways) began to introduce

two different fare products for the same flight - lower fares for passengers who book in

advance and higher fares for passengers who book closer to the date of departure2 . This

presented the airline with a problem in determining the number of seats that needed to be

protected for late full fare passengers and revenue management (then known as yield

management) was thus born.

Despite these early pioneers of revenue management, the main catalyst for the intensive

development of revenue management techniques can be traced back to the deregulation

of the airline industry in 1979, where Congress granted carriers control over their own

respective product offerings3 .

'Smith, B.C., J.F. Leimkuhler, R.M. Darrow. 1992. Yield Management at American Airlines. Interfaces.

Volume 22, Issue 1, pp. 8-3 1.

2 McGill, J. I., G. J. van Ryzin. 1999. Revenue Management: Research Overview and Prospects.

TransportationScience. Volume 33, Issue 2, pp. 233-256.

3 General Accounting Office. 1999. Airline Deregulation: Changes in Airfares, Service Quality, and

Barriers to Entry. Report to Congressional Requesters. GAO/RCED-99-92. Washington, D.C.

-

15 -

With deregulation, the airlines started to compete on an origin-destination (OD) basis

where passengers choose between airlines and products on a city-pair, independent from

any transits or stopovers in between. As pricing structures evolved and prices dropped in

many markets reflecting the more competitive environment, yield management became

more critical. Airlines began to realize that in order to maximize their revenues, it would

be optimal if they would be able to charge each passenger a fare that matches their

individual willingness to pay.

As we can see from Figure 1-1, if an airline decides to charge a single high fare (P1 )

during the whole booking period in order to target high-yield passengers, its flights will

depart with a very low load factor (Qi out of Q4 seats) because supply exceeds demand at

that price. In this case, the revenue management system overprotects the inventory as it

refuses to sell the empty seats at a lower price due to inaccurate expectation that higher

yield passengers will book in the future. There is a lost of revenue not only due to

consumer surplus (Area ABP 1 ) but also due to unsold seats (Area BQ 1 Q4E).

Price

A

Capacity of Aircraft

Loss of Revenue

(Consumer Surplus)

P2

D

P3

L

E

z

P4

Q0

Q1

Q

Q2

Q3

Demand

QQuantity

Q4

Figure 1-1: Use of Differential Pricing to Maximize Revenue

Conversely, if the airline decides to charge a single low fare in order to fill up its flights

(P2), most of its passengers will end up paying a fare that is lower than their willingness

to pay. As a result, the airline experiences a lost of revenue due to consumer surplus

(Area AEP 4 ). There is a dilution of revenue as the strong revenue streams an airline can

expects from its high yield passengers is diluted with low fares even though the load

factor is very high (full capacity Q4).

- 16 -

So clearly, single fare policies are unappealing because they result in lost revenue from

unsold seats and/or diluted fares. The use of differential pricing therefore became a core

component of successful revenue management'. By setting different fares (P1 to P4 ) for

identical seats on a plane, an airline is able to reduce the amount of revenue loss from

diluted fares and maintain a healthy load factor (see Figure 1-1).

Although in reality, it would be difficult to charge each passenger a fare that matches

their individual willingness to pay, it is however possible to group the passengers into

different segments and practice differential pricing for each of these segments. By putting

different fare restrictions such as advance purchase, Saturday night stay, refund charges

and cancellation fee for each fare classes, airlines have been segmenting the markets into

two main groups.

First, there are the business passengers who are less price-sensitive and usually book their

tickets closer to the date of departure. Then there are the leisure passengers who are

known to be more price-sensitive and are more flexible in terms of schedule. Such fare

restrictions are more strongly enforced for the lower fare products, thus creating much

disutility for business passengers, who in the end, are willing (or forced) to pay more to

avoid the restrictions.

However, complication arises as high yield passengers tend to book late whereas leisure

passengers with a lower willingness to pay tend to book early. There is thus a need for

revenue management systems to accurately forecast the high yield demand that would be

coming and find a way to optimize the allocation of seats to a specific fare class with its

associated restrictions.

1.2

CHANGES IN THE INDUSTRY

In recent years however, airlines' ability to prevent business travelers from buying down

(buying a lower priced product) has decreased tremendously. The emergence and growth

of low fare carriers has changed the industry. Unlike their legacy counterparts, these new

airlines have very low operating costs. Thus they are able to provide frequent and cheap

service to popular destinations at comparable service. In addition to lower fares, the other

visible characteristic of these new airlines is their use of simplified fare structures, which

although is less complex and less confusing, is also far less differentiated than the rest of

the major airlines.

Belobaba, P. P. 1998. Airline Differential Pricing for Effective Yield Management. The Handbook of

Airline Marketing, D. Jenkins (ed.). The Aviation Weekly Group of the McGraw-Hill Companies, New

4

York, NY, pp. 349-361.

-17-

This together with the ease of information gathering through the Internet in this day and

age, the market power has been shifting to the consumers who almost have full

information on all the different products that are available in the market. As a result, the

legacy airlines have no choice but to match their competitors' fares in markets where they

compete head on to avoid losing too much revenue and market share.

In these competitive markets, they changed their fare structure - compressing fare ratios,

removing some if not all of the restrictions and advance purchase requirements. This

resulted in a "semi-restricted" fare structure where there are homogenous fare classes that

are undifferentiated except by price and also distinct fare classes which are still

differentiated by booking restrictions and advance purchase requirements. In these new

fare environment, the use of traditional revenue management systems (which were

developed based on the assumption of independence of demand of fare class) tend to lead

to a spiral down effect as the airlines have to deal with customers who now

systematically buy the lowest fare available in the absence of distinctions between the

fare classes.

Thus, with little or no barriers to segment the market according to each passenger group's

willingness to pay, there is now a need to rethink the way seats are sold. For how would

seat inventory control algorithm be able to trade-off one fare product with another when

different fare products no longer exist?

1.3

NEW / RECENT APPROACHES

Given the quick expansion of the low-cost carriers and the simplification of fare

structures, new algorithms have been recently developed to provide for an optimal seat

inventory control that would counteract the challenges discussed previously in section 1.1

and 1.2.

1.3.1

Forecasting and Sell-up

Forecasting is the estimation of bookings-to-come by fare class and by flight using

historical unconstrained data obtained from previous "equivalent" flight booking process

records. In order for the revenue management system to work (setting aside an optimal

number of seats for the late higher yield passengers), forecast needs to be as accurate as

possible. With no distinction between products, every passengers would buy the lowest

fare available and it becomes impossible for the revenue management system to forecast

demand for each fare class using traditional methods as demand for highest classes do not

materialize. Furthermore, no observed demand in the historical database means that no

demand can be forecast for the highest classes in future.

-18-

One way of overcoming this problem is through the use of sell-up probability, which is

the probability that a passenger is willing to buy a ticket at a higher fare for the same

flight if he is denied booking for the requested lower fare product. By taking this

probability into account, the optimization process will close down lower fare classes

whenever necessary and protect more seats for higher yield passengers. This would thus

force passengers with higher willingness-to-pay to buy-up when they are denied booking

for their first (and usually lower fare product) request.

However, in order to use these sell-up probabilities in the revenue management systems,

one need to know how to estimate them dynamically during the forecast process as the

probabilities depend on the specific flight and they would not be optimal if set arbitrarily.

To meet this need, several developments had occurred in the area of revenue management

algorithms for less restricted fare structures such as Q-forecasting', Hybrid forecasting6

by Belobaba/Hopperstad and Fare Adjustment by Isler and Fiig?.

1.3.2

QiHybrid Forecasting

Q-forecasting was developed for fully undifferentiated fare structures where there is

absolutely no distinction between the different fare products and passengers would buy

the lowest available fare. Given this buying behavior, Q-forecasting seeks to forecast

only the lowest class demand (Q-class) and using estimates of passenger's willingness-topay, closes down lower fare classes in order to force "sell-up" into higher ones.

Hybrid forecasting on the other hand was designed for semi-restricted fare structures. It

seeks to classify all bookings into two categories - "product-oriented" demand and

"price-oriented" demand. It then predicts the future demand of both these two demand

categories (which are assumed to exhibit different booking behavior) using different

methods of forecasting for each category.

1.3.3

Fare Adjustment

7

Developed by Isler and Fiig at Scandinavian Airlines (SAS) and Swissair, Fare

Adjustment aims to increase airline revenues in a network where different fare structures

co-exist, typically a less restricted fare structure with almost no restrictions and a

tradition restricted fare structure. Using estimates of passengers' willingness to pay, it

adjusts the less restricted fares used by the network seat allocation optimizer (not the

Belobaba and Hopperstad, Q investigations - Algorithms for Unrestricted Fare Classes, PODS

presentation, Amsterdam, 2004

6Belobaba, P., C. Hopperstad. 2004. Algorithms for Revenue Management in Unrestricted Fare Markets.

Presented at the Meeting of the INFORMS Section on Revenue Management, Massachusetts Institute of

Technology, Cambridge, MA.

7 Isler and Fiig, SAS O&D Low Cost Project, PODS presentation, Minneapolis-St Paul, 2004

5

-19-

actual fares offered to passengers) to lower fare buckets and proactively close down

selected lower fare classes, thus forcing passengers to pay more for the higher-priced fare

products.

1.4

OBJECTIVES OF THE THESIS

As discussed, demand forecast is a critical component of the RM process. A precise and

sophisticated revenue management system can become useless if it uses inaccurate

forecasted demand for its seat allocation optimizer. Research have shown that by

changing the forecasting method, from the current more commonly used standard (pickup) forecasting to Q- or hybrid forecasting, airlines are able to experience a great increase

in revenue.

However, the impact of fare adjustment on airlines' revenue is still unclear. Research into

fare adjustment has so far been focusing on price-oriented passengers with the airline

using DAVN in a 2 carrier network. In his thesis, Cl6az-Savoyen' showed a 0.2%

increase in revenue with fare adjustment alone (standard forecasting) in a totally

undifferentiated environment using DAVN and a 0.63% increase in revenue when fare

adjustment is combined with Q-forecasting. Reyes' on the other hand investigated the

impact of fare adjustment and hybrid forecasting with DAVN in a semi-restricted

environment. The results showed that the use of fare adjustment alone (with standard

forecasting) in DAVN does not produce any revenue improvement while a combination

of fare adjustment and hybrid forecasting produces an increase of 4.15% revenue.

Therefore, the goal of this thesis is to provide a more comprehensive investigation into

the effectiveness of fare adjustment as a tool to improve airline revenues in this new

environment. This thesis will extend the investigation of the effectiveness of Fare

Adjustment with standard forecasting to other revenue management systems such as

EMSRb and Heuristic Bid Price.

In addition, it would also examine the impact fare adjustment has in a 4 carrier network

with mixed fare structure where different fare structures are used for different markets.

This would thus allow us to further investigate the results when fare adjustment is used in

all markets versus when fare adjustment is used only in markets with competition from

low cost carriers. Furthermore, we will also look at the impact fare adjustment has when

it is used in the reservation system instead of the revenue management system itself.

8 C16az-Savoyen,

R. L. 2005. Airline Revenue Management for Less Restricted Fare Structures. Master's

thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

9 Reyes, M. H. 2006. Hybrid Forecasting for Airline Revenue Management in Semi-Restricted Fare

Structures. Master's thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

-

20-

1.5

ORGANIZATION OF THE THESIS

This thesis consists of three main parts: the literature review, PODS simulator approach

to Revenue Management, and an analysis of the results of PODS simulations.

Chapter 2 presents a discussion of previous work done on revenue management with an

emphasis on the problem of simplified and mix fare structures examined in this thesis.

Topics covered in the chapter include forecasting, specific RM models, the emergence of

simplified fare structures due to LCCs, and a discussion of fare adjustment technique.

An overview of the Passenger Origin-Destination Simulator (PODS) that is used for the

thesis is provided in Chapter 3. We will look at the workings of PODS with a focus on

the elements relating to standard forecasting and fare adjustment, as well as an

introduction to the simulations that were performed.

The results of the simulations are presented in Chapters 4 and 5. Chapter 4 deals mainly

with fare adjustment in the revenue management system while Chapter 5 deals with the

results of fare adjustment in the reservation system. Not only are the potential revenue

benefits (or losses) quantified, we also analyze some of the underlying effects fare

adjustment have on loads, yields, fare class mix, etc. in order to isolate the ramifications

of each experiment.

Finally, Chapter 6 attempts to summarize the experiments performed, as well as the

revenue benefits possible with the use of fare adjustment in the revenue management

system and reservation system. Several directions for future work are also presented.

- 21 -

-22-

2.

LITERA URE REVIEW

Revenue management has been much studied over the past 25 years. In the beginning, it

could have been considered as a narrow area of interest to academics and airline

operations enthusiast. Today however, revenue management is an indispensable tool that

is used by nearly every carrier in the world seeking to maximize their revenue.

This chapter starts by reviewing the evolution of revenue management systems and the

use of forecasting and seat inventory control in the airline industry. Next, we examine the

emergence of low cost carriers and the resulted less-restricted fare structure which require

changes in traditional revenue management. This chapter then concludes with the

presentation of two revenue management methods that were developed for the new

environment: Q/Hybrid forecasting and Fare Adjustment.

2.1

REVENUE MANAGEMENT

Using a combination of pricing and seat inventory control, the goal of revenue

management has been to determine what amount of capacity to offer to which customers

at what price so as to maximize revenue. Although this objective of revenue management

has never changed, our understanding of the problem and the approaches to solving this

problem has changed quite tremendously in the relatively short amount of time.

A very good review and description of this evolution of revenue management models in

the airline industry can be found in McGill and Van Ryzin'". Barnhart et al." and Clarke

and Smith" on the other presented more detailed overviews of fleet assignment, revenue

management and aviation infrastructure operations, although Clarke and Smith1 2 focused

more on the contributions of operations research to the airline industry.

The earliest revenue management system came in the form of the databases that airlines

used to keep track of their bookings. However, the process was more like data collection

or bookings observation rather than actual revenue management. This process was soon

improved upon in the second generation of revenue management system where airlines

were able to track the bookings of a specific flight before departure and compare that to

the forecasted booking patterns.

' McGill, J. I., G. J. van Ryzin. 1999. Revenue Management: Research Overview and Prospects.

TransportationScience. Volume 33, Issue 2, pp. 233-256.

'1 Barnhart, C., P. Belobaba, A. R. Odoni. 2003. Applications of Operations Research in the Air Transport

Industry. TransportationScience, Volume 37, Issue 4, pp. 368-391.

12

Clarke, M., B. Smith. 2004. Impact of Operations Research on the Evolution of the Airline Industry.

Journal of Aircraft. Volume 41, Issue 1, pp. 62-72.

-

23

-

Yet, advances in operations research were not integrated into the revenue management

process until the late 1980's and early 1990's when the ability to forecast and optimize

each future flight leg by booking classes was added to the third generation revenue

management system. And as shown in Figure 2-1, a typical third generation system thus

consists of three component models: the demand forecaster, the fare class mix optimizer

and the overbooking module.

Input Data

Revenue

Data

Historical

Booking

Data

Actual

Bookings

N

Data

RM Components

MOl

I

Output Data

Z

Figure 2-1: Example of a Third Generation System

1,1

Developed to reduce revenue loss due to no-shows, overbooking models have the longest

research history of among the three component models. It involves trading off between

denied boarding (which affects the image of the airline) and potential revenue loss from

unsold or spoiled seats by accepting more reservations than what is actually available for

a flight. An early, static overbooking model was produced by Beckman" and further

Belobaba, P.P. 2002. Airline Network Revenue Management: Recent Developments and State of the

Practice. The Handbook ofAirline Marketing, D. Jenkins (ed.). The Aviation Weekly Group of the

McGraw-Hill Companies, New York, NY, pp. 141-156.

1 Beckman, J. M. 1958. Decision and Team Problems in Airline Reservations. Econometrica.Volume 26,

pp. 134-145.

13

-

24-

researched by Thompson", Taylor" and Littlewood". Dynamic optimization approaches

to overbooking had also been developed by Rothstein" and Alstrup et al.' 9 More

information on the development of overbooking research can be found in McGill and

Van Ryzinl0 . For the purpose of this thesis however, no overbooking models will be used

in the simulations. Rather, we will only look at the forecasting and optimizer models

which are further elaborated in Section 2.1.1 and Section 2.1.2.

Using the airline's database of historical bookings, current booking data, revenue

(pricing) data as well as no-show data, the revenue management system then generates

recommended optimal booking limits for each flight and fare class. Such third generation

systems are used today by the vast majority of airlines across the world, and they

typically generate revenue improvement of 2% to 6% as compared to no seat inventory

control ",1.

2.1.1

Forecasting

As mentioned in Section 1.1, passengers with higher willingness-to-pay (typically

business travelers) also tend to make their bookings much later in the booking process

than those with a low willingness-to-pay. Therefore when practicing revenue

management, the airline have to make a initial guess as to how many seats to offer to the

early-booking but low-fare passengers and how many seats to reserve for the high-yield

passengers. Although the booking limits are dynamic in that they changes as time

progresses and bookings come in (i.e. the airline starts to have actual information about

the specific flight as opposed to just forecasted information), good initial estimates are

necessary to avoid filling up the plane early in the process with too many low-fare

passengers and later having to turn away high-fare demand.

Therefore, forecasting is arguably the most critical component of airline revenue

management because of the direct influence forecasts have on the booking limits that

determine airline revenues. It provides airlines with projected demand by fare class for a

given flight, based on complete historical observations of similar flights and incomplete

current observations for future flights. Different forecasting methods can be used to

obtain such estimate by transforming the data in different ways, using some or all of the

information that is available.

15

Thompson, H.R. 1961. Statistical Problems in Airline Reservations Control. OperationsResearch

Quarterly. Volume 12, pp. 167-185.

16 Taylor, C. J. 1962. The Determination of Passenger Booking Levels. "d AGIFORS Annual Symposium

2

Proceedings,Fregene, Italy.

7 Littlewood, K. 1972. Forecasting and Control of Passenger Bookings. 12'hAGIFORSAnnual Symposium

Proceedings,Nathanya, Israel, pp. 95-117.

" Rothstein, M. 1968. Stochastic Models for Airline Booking Policies. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of

Engineering and Science, New York University, New York, NY.

19 Alstrup, J., S. Boaz, O.B.G. Madsen, R. Vidal, V. Victor. 1986. Booking Policy for Flights with Two

Types of Passengers. European Journal of Operations Research, Volume 27, pp. 274 -288

-

25

-

Pick-up forecasting, exponential smoothing, moving average, regression and

multiplicative pick-up are some of the revenue management forecasting methods that are

commonly used in practice20' ". However, an evaluation of the performance of several

forecasting techniques conducted by Wickham" found that pick-up models consistently

outperformed simple time-series and regression models. As we will be focusing on pickup forecasting in this thesis, this model is reviewed in greater detail in the next section.

For information on other forecasting techniques, one can refer to Zeni21 , Wickham2 2 ,

Zickus23 , Skwarek' and Gorin'.

Whereas a simple time series forecast would simply be the average of final bookings on a

set of similar flights, pick-up forecasting goes one step further by including the average

incremental bookings received in each time interval before departure. This pick-up data,

obtained from booking information of previous flights (i.e. historical data), is added to

the number of bookings on-hand to forecast the total demand at the end of a particular

period.

Alternatively, the advanced pick-up model (developed by L'Heureux 2 ) can also be used.

Similar in formulation, it builds on the classical model by incorporating data from flights

that have not yet departed. However, we will only be using the classical pick-up model

for this thesis. For additional information on pick-up forecasting, readers can refer to

Wickham22 , Zickus2 3 and Skwarek 2 4 .

2.1.2

Seat Inventory Control

As discussed earlier, the use of differential pricing results in the need for airlines to make

use of seat inventory control (either on a single leg or in a network) to ensure that the

low-fare leisure passengers do not consume all the seats on high demand flights.

Weatherford, L. 1999. Forecast Aggregation and Disaggregation. IATA Revenue Management

Conference Proceedings.

21 Zeni, R. H. 2001. Improved Forecast Accuracy in Revenue

Management by Unconstraining Demand

Estimates

from Censored Data. Ph.D. Thesis. Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, Newark, NJ.

22

Wickham, R. R. 1995. Evaluation of Forecasting Techniques for Short-Term Demand

of Air

Transportation. Master's Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

23 Zickus, J. S. 1998. Forecasting for Airline Network Revenue

Management: Revenue and Competitive

Impacts. Master's Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

24 Skwarek, D. K. 1996. Competitive Impacts of Yield Management

Systems Components: Forecasting and

Sell-up Models. Master's Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

25 Gorin, T. 0. 2000. Airline revenue management: sell-up

and forecasting algorithms. Master's thesis,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

26 L'Heureux, E. 1986. A New Twist in Forecasting Short-term Passenger Pickup. 26 AGIFORS Annual

Symposium Proceedings,Bowness-on-Windemere, England, pp. 248-261.

20

-

26

-

2.1.2.1

Leg based Control

The most commonly used fare class mix allocation is the idea of serial "nesting" of fare

classes which was first solved by Littlewood 17 at BOAC for the case of a single-leg two

fare classes environment and expanded upon by Bhatia and Parekh" and Richter".

Instead of making the allocating of seats to the two fare classes separately, seats in the

higher fare class are protected by limiting the number of seats sold in lower fare classes

based on the demand forecast for each class, as well as the expected seat revenue.

This approach was subsequently generalized to a heuristic by Belobaba29 30 to determine

nested booking limits for a flight with any number of fare class using the concept of

Expected Marginal Seat Revenue (EMSR). He subsequently proposed a small adjustment

to this heuristic to make it more robust. This new heuristic became known as the EMSRb

method" and it has become one of the most widely used methods in the industry for

establishing booking limits on a flight leg basis.

By assuming that the fare classes demand are normal and independent, EMSRb uses legbased demand forecasts by fare class to produce leg-based seat protection levels for the

nested booking classes. The booking limits are determined based on the expected

marginal revenue, which is the probability of selling an additional seat in a given fare

class multiplied by the average fare of the booking class under consideration. Thus seats

are protected for a fare class as long as the seats' expected marginal revenue is greater or

equal to the fare in the next lower fare class. In addition, by creating joint demand

distributions (using mean demand and standard deviation from the individual classes), the

EMSRb approach allows for joint upper classes to be protected from the fare class just

below. More information on the EMSRb algorithm can be found in Mak", Lee" and

Williamson".

Bhatia, A.V. & Parekh, S.C. 1973. Optimal Allocation of Seats by Fare, AGIFORS Reservations and

Yield Management Study Group.

28 Richter, H. 1982. The Differential Revenue Methods to Determine Optimal Seat Allotments

by Fare

362

pp

339

Proceedings,

Symposium

Annual

Type,

22"

AGIFORS

29

Belobaba, P. P. 1987. Air Travel Demand and Airline Seat Inventory Management. Ph.D. Thesis,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

30

Belobaba, P.P. 1989. Application of a Probabilistic Decision Model to Airline Seat Inventory Control,

Operations Research, Volume 37, pp. 183 - 197

31 Belobaba, P. P. 1992. "Optimal versus Heuristic Methods for Nested Seat Allocation."

AGIFORS

Reservations Control Study Group Meeting. Brussels, Belgium.

32 Mak, C. Y. 1992. Revenue Impacts of Airline Yield Management. Master's Thesis,

Massachusetts

Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

3 Lee, A. Y. 1998. Investigation of Competitive Impacts of Origin-Destination Control using PODS.

Master's Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

3 Williamson, E. L. 1992. Airline Network Seat Inventory Control: Methodologies and Revenue Impacts.

Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

27

-

27

-

Others such as Brumelle and McGill", Curry36' Robinson", and Wollmer" approach the

multiple nested class problems using optimal formulations to determine the optimal

nested booking limits for multiple fare classes. However, such alternatives require a lot

more computational effect and their numerical results suggest that the much simpler

EMSRb is close to optimal.

2.1.2.2

Network O-D Control

Although leg-based control is vastly used in the industry today, it was designed to

maximize yields and not total revenue. Seats for connecting itineraries must be available

in the same class for all legs of the itinerary in order for the airline to accept the booking.

This means that bottle-leg legs can thus block out long-haul passengers even though their

contribution to the total revenues could be higher than local passengers.

Therefore, an airline would need to increase the availability of seats to high-revenue

connecting passengers regardless of yield in a network environment. However, at the

same time, the airline would also need to prevent these same connecting passengers from

displacing high-yield local passengers on full flights. The revenue management system

thus needs to be able to respond to different flight requests with different seat availability

based on the network value of the request. For this reason, much effort has been

expended to develop algorithms for path-based protection of booking classes (or OriginDestination Fare Class control).

First developed and implemented by American Airlines39 , the use of "virtual value

buckets" is one approach to network OD control. Here, the fixed relationship between

fare type and booking class is abandoned. Instead, the value buckets are defined

according to their revenue value, regardless of the restrictions. Each ODF is then

assigned to a revenue value bucket base which determines the availability of seat to the

ODF request. However, this method of grouping ODF gives priority to all long haul

higher revenue passengers over short haul lower revenue passengers, which does not

necessarily lead to network revenue maximization.

35

Brumelle, S. L. and McGill, J. I. 1988. Airline Seat Allocation with Multiple Nested Fare Classes. Paper

presented at the Fall ORSA/TIMS Conference, Denver, CO. Also presented at the University of British

Columbia, 1987.

36 Curry, R. E. 1990. Optimal Airline Seat Allocation with Fare Classes Nested by Origin and Destinations.

TransportationScience. Volume 24, Issue 3, pp. 193-204.

37

Robinson, L. W. 1995. Optimal and Approximate Control Policies for Airline Booking with Sequential

Nonmonotonic Fare Classes. OperationsResearch. Volume 43, Issue 2, pp. 252-263.

38

Wollmer, R. D. 1992. An Airline Seat Management Model for a Single Leg Route when Lower Fare

Classes Book First. OperationsResearch. Volume 40, Issue 1, pp. 26-37.

39 Smith, B.C. and Penn, C.W. 1988. Analysis of Alternate Origin-Destination Control Strategies,

AGIFORS Annual Symposium Proceedings,vol. 28, pp 123 - 144.

-

28

-

A slight adjustment was then proposed by American3 9 and United' to make the value

bucket assignments base on an ODF "net value", which take into account the

displacement of up-line and down-line passengers. The specific virtual bucket method

that will be investigated in this thesis is known as Displacement Adjusted Virtual Nesting

(DAVN). Using a deterministic linear program, DAVN calculates a "pseudo fare" for

each fare class in the network. This "pseudo fare" corrects the revenue value for network

displacement effects by deducting the revenue displacement that might occur on

connecting flight legs if the passenger's request for a multiple-leg itinerary is accepted

(other than the legs under consideration) from the total itinerary fare. More information

on virtual value buckets and DAVN can be found in Lee, Vinod" and Williamson.

Another approach to network O-D control is the Bid Price model as discussed in Smith

and Penn , Simpson42 and Wei43 . This is a much simpler inventory control than virtual

buckets as the airline only need to store the bid price (which is the approximated

displacement cost) value for each leg. The ODF is then compared to the itinerary bidprice at the time of availability request. If the bid-price is greater than the ODF, the

request will be rejected. Otherwise, the request will be accepted by the airline.

Specific bid price algorithms include the Network Bid Price (NetBP) method, the

Probabilistic Bid Price (ProBP) as described by Bratu" and the Heuristic Bid Price (HBP)

developed by Belobaba", which will be the main bid-price method used and discussed in

this thesis.

2.2

LOW COST CARRIERS AND LESS-RESTRICTED FARE ENVIRONMENT

The emergence of the low cost carriers (LCCs) has dramatically changed the landscape of

the airline industry. The main characteristic of the LCC model, apart from the very low

costs, is its simple fare product structure. Whereas the legacy airlines tend to have a mix

of many different types of tickets (also known as fare products) ranging from high to low

fare with various restrictions, LCCs tend to have only low fares with a few fare products

for each O-D market and very few restrictions if any.

40

Wyson, R. 1988. A Simplified Method for Including Network Effects in Capacity Control, AGIFORS

Annual Symposium Proceedings, vol. 28, pp 113 - 121.

41 Vinod, B. 1995. Origin and Destination Yield Management. The Handbook of Airline Economics,

D.

Jenkins (ed.). The Aviation Weekly Group of the McGraw-Hill Companies, New York, NY, pp. 459-468.

42 Simpson, R.W. 1989. Using Network Flow Techniques to Find Shadow Prices for Market

and Seat

Inventory Control, Memorandum M89-1, MIT Flight Transportation Laboratory, Cambridge, MA.

43

Wei, Y.J. 1997. Airline O-D Control using Network Displacement Concepts, Master's Thesis,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

4 Bratu, S. J-C. 1998. Network Value Concept in Airline Revenue Management. Master's Thesis,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

45 Belobaba, P. P. 1998. The Evolution of Airline Yield Management: Fare Class to Origin-Destination Seat

Inventory Control. The Handbook of Airline Marketing, D. Jenkins (ed.). The Aviation Weekly Group of

the McGraw-Hill Companies, New York, NY, pp. 285-302.

-

29

-

25

In his Ph.D. thesis, Gorin provides a comprehensive summary of changes in the U.S.

airline industry since deregulation, focusing especially on the entry and impact of LCCs.

In addition, comparisons of the characteristics that are traditionally associated with the

LCCs' model and legacy carriers' model can be found in Weber and Thie 4 , Dunleavy

and Westerman 7 , Cl6az-Savoyen 8 and Reyes 9 .

In response to the increasing competition, legacy carriers began to partially or fully match

the LCCs in terms of their fare products by lowering their fares, removing certain

restrictions and/or reducing the advance purchase requirements 8 ' 49, 50, 51. With their

revenue management systems still based on highly segmented market structures, this

advent of less differentiated fare environment made it difficult or even impossible for

airlines to effectively segment demand as the restrictions fencing business and leisure

passengers into their respective fare classes disappear.

With no differentiation among the fare products (except price), passengers naturally

would buy the lowest fare available (even though their willingness-to-pay is much

higher). Such buying down behavior results in a spiral-down effect where airlines get

stuck in a cycle leading to lower and lower revenues (Figure 2-2).

With fewer high-fare products being purchased by passengers, airlines' historical

booking data contains fewer records of these products being sold and the revenue

management system forecasts less demand for these products. This in turn results in less

seats being protected for the higher fare classes and more seats being made available to

the lower fare classes. This surplus of lower fare class seats starts the whole cycle again

and with each iteration, revenues becoming more diluted as there is now even less

inducement to buy high-priced products.

46

Weber, K. and Thiel, R. 2004. Optimisation Issues in Low Cost Revenue Management.

AGIFORS

Reservations & Revenue Management Study Group Meeting, Auckland, New Zealand.

47

Dunleavy, H. and Westermann, D. 2005. Future of Airline Revenue Management. Journalof Revenue

and PricingManagement. Volume 3, Issue 4, pp. 380-282.

48 Windle, R. and Dresner, M. 1999. Competitive Responses to Low Cost Carrier Entry. Transportation

Research PartE, Volume 35, pp. 59-75.

49 Forsyth, P. 2003. Low-cost Carriers in Australia: Experiences and Impacts. Journal of Air Transport

Management,Volume 9, Issue 5, pp. 277-284.

'0 Morrell, P. 2005. Airlines within Airlines: An Analysis of US Network Airline Responses to Low Cost

Carriers, Journalof Air TransportManagement,Volume 11, Issue 5, pp. 303-312.

51 Ratliff, R., Vinod, B. 2005. Airline Pricing and Revenue Management: A Future Outlook. Journalof

Revenue and Pricing Management.Volume 4, Issue 3, pp. 302-307.

-

30-

High-Fare Demand

"Buy Down" to Lower

Fare Classes

More Seats Made

Available at Lower

Fare Classes

..

.

T

Less Protection for the

Higher Fare classes

a

a

L

Fewer Bookings

Observed in Higher

Fare Classes

a

Lower Forecast of

High-Fare Demand

Figure 2-2: Spiral-Down Effect 8' 9

For a mathematical model of the spiral down effect, the reader is referred to Kleywegt et

al." and Cooper et al." In addition, the effects of buy-down and spiral down as a result of

fare structure simplification are also described and analyzed by Cusano", CldazSavoyen 8 , Ozdaryal and Saranathan"5 and Dar 6 .

2.3

REVENUE MANAGEMENT TOOLS FOR THE NEW ENVIRONMENT

As discussed in the previous section, the fare environment for legacy carriers has changed

as they react to the emergence of the LCCs. However, the introduction of fare products

with almost no restrictions or advance purchase requirements violates the fundamental

52

Kleywegt, A. J., T. Homem-de-Mello, W. L. Cooper. 2003. Models of the Spiral Down Phenomenon.

Paper presented at the Meeting of the INFORMS Section on Revenue Management, Columbia University,

New York, NY.

5 Cooper, W. L., T. Homem-de-Mello, A. J. Kleywegt. 2004. Models of the Spiral-down Effect in Revenue

Management. Working Paper, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Minnesota,

Minneapolis, MN.

54 Cusano, A. J. 2003. Airline Revenue Management under Alternative Fare Structures. Master's Thesis,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

55 Ozdaryal, K., Saranathan, B. 2004. "Revenue Management in Broken Fare Fence Environment."

AGIFORS Reservations & Revenue Management Study Group Meeting, Auckland, New Zealand.

56

Dar, M. 2005.

"Spiral-Down" in Intermediate Fare Structures. PODS ConsortiumMeeting, Copenhagen,

Sweden.

-31-

assumption of independence of demand by fare class on which traditional revenue

management methods are based. There is therefore a need to develop new methods that

can adapt to this new environment.

2.3.1

Q / Hybrid Forecasting

To deal with totally unrestricted fare structure where the only differentiator is price,

Belobaba and Hopperstad , 6 have developed modified forecasting and optimization

approaches that do not rely on independent class demand. By transforming historical

bookings into Q-equivalent bookings (i.e. the total potential demand for the lowest

available class), "Q-forecasting" forecast demand only at the lowest classes (denoted as

Q-class). It then uses estimates of passengers' willingness-to-pay to close down lower

fare classes in order to force some of the Q-bookings to sell-up onto higher fare classes

(using the existing fare class structure to set the booking limits). This method has proved

to be an effective technique for forecasting when restriction-free fare structures are used.

However, Q-forecasting is not completely appropriate when an airline uses a semirestricted fare structure, where there are undifferentiated fare classes (usually at the lower

fare classes, differentiated only by price) and also higher fare classes that are

differentiated by some restrictions from the lower fare classes. This is because the

restrictions would deter some passengers from buying certain classes and therefore, not

all the passengers in this case would be price-oriented. Using traditional forecasting

methods would also prove to be suboptimal as the presence of the undifferentiated fare

classes again invalidates the assumption of independence among the fare classes.

To solve this problem, hybrid forecasting was developed by Boyd and Kallesen". Using a

new segregation of demand (yieldable versus priceable passengers), hybrid forecasting

aims to classify all bookings into one of these two demand categories and a separate

demand forecasting method is used for each segment.. For product-oriented demand,

bookings are treated as a historical data for the given class, and standard time series

forecasting applied. For price-oriented demand on the other hand, Q-forecasts by

willingness-to-pay based on expected sell-up behavior is used. More information on

hybrid forecasting can be found in Reyes's 9 thesis where he examined the process and

demonstrated that hybrid forecasting can improve an airline's network revenue by about

3% as compared to traditional forecasting methods.

57

Boyd, E. A., Kallesen, R. 2004. The Science of Revenue Management when Passengers Purchase the

Lowest Available Fare. Journalof Revenue and PricingManagement. Volume 3, Issue 2, pp. 171-177.

-

32

-

2.3.2

Fare Adjustment

Developed by Fiig and Isler7 in 2004, Fare Adjustment methods also aim to address the

problem of the coexistence of different fare structures in a single leg. With the entrance

of LCCs and the need to match their fare structures, legacy airlines typically end up with

a network consisting of a traditional, restricted fare structure (connecting passengers)

and a less-restricted, low-cost-carrier-type fare structure (local passengers).

Therefore, there would be a situation where an airline using DAVN may have 2 ODFs,

each of them belonging to a different OD market and fare structure, co-existing in the

same virtual bucket (Figure 2-3).

Restricted Fare

Structure

Pseudo Fare

Unresti

Fare Str

Pseudo Fare

Virtual

Buckets

Closed

Buckets

Figure 2-3: Co-existence of Different Fare Structures in a Network8

Conflict then arises because of the different characteristics of these two structures. Under

the traditional restricted structure, demand is assumed to be independent and sell-up

behavior is not taken into account. Demand in such a fare structure is segmented by the

restrictions and advance purchase requirements thus reducing the consumer surplus.

However, in the less-restricted fare structure, revenues are maximized by incorporating

sell-up behavior into forecasting and optimization. In this case, higher-class bookings are

achieved by closing down lower classes.

Thus, the closure of the bucket V4, which automatically make both ODF unavailable,

may be optimal under the less restricted strategy but not under the restricted strategy and

revenue will not be maximized.

-

33

-

With fare adjustment, we can lower the pseudo fare (the fare that is used by the system to

decide on the seat allocations and thus, may differ from the actual fare offered to

customers) of the unrestricted fare structure by a certain amount in order to shift it to a

lower virtual bucket. The amount to be decreased is referred to as the Price Elasticity cost

(PE cost). It accounts for the risk of buy-down and is dependent on the passenger

willingness-to-pay. With the introduction of this PE cost, we can now decouple the fares

which previously were in the same virtual buckets and thus, manage the two different

fare structures separately from each other. The airline can therefore close down the

unrestricted fare earlier, yet at the same time, keep the restricted fare open (Figure 2-4).

Restricted Fare

Structure

Unrestricted

Fare Structure

Pseudo Fare

Virtual

Buckets

-'

V4

------------a

~

Pseudo Fare - PE Cost

Closed Buckets

Figure 2-4: Using Fare Adjustment to Decouple the Fare Structures8

Cl6az-Savoyen 8 tested the FA methodology in the context of the DAVN optimization

process and concluded that FA had the potential to be an effective technique for seat

inventory control in restriction-free fare structure environments where two airlines are

competing head-to-head. It provides a 0.2% increase in revenue with standard forecasting

and a 0.63% increase when used with Q-forecasting.

Vanhaverbeke" and Reyes9 on the other hand, tested its applicability in a two airline

network with semi-restricted fare structure environments and both obtained an increase in

revenue ranging from 3.6% to 4.2% when FA is used with Hybrid Forecasting. Although

the use of FA alone in DAVN did not produce any revenue improvement, it increases

revenue obtained from HF alone by 1% to 1.5%. Vanhaverbeke" also tested the impact of

FA and Hybrid Forecasting when used with dynamic programming. However, the results

in this scenario were not conclusive.

Vanhaverbeke, T. 2005. DAVN with Hybrid Forecasting and Fare Adjustment

in Semi-Restricted

Environments. PODS ConsortiumMeeting, Boston, USA.

59

Vanhaverbeke, T. 2005. Dynamic Programming with Hybrid Forecasting and Fare Adjustment. PODS

Consortium Meeting, Boston, USA.

58

-

34-

2.4

CHAPTER SUMMARY

In this chapter, we started with a review of the literature on revenue management and its

three component models, with our discussion focusing mainly on forecasting and seat

inventory control. We then went on to take a look at the entry of Low Cost Carriers and

their impact on the fare structures of legacy airlines in section 2.2; here we described the

inadequacy of traditional revenue management in a less restricted fare environment and

how it leads to a spiral down effect. To reduce the negative impact of a less restricted fare

structure, Section 2.3 introduces reader to two new revenue management tools that were

designed for use in such simplified fare structures: Q/hybrid forecasting and fare

adjustment.

Fare adjustment has been shown to be effective when used with Q/hybrid forecasting for

airlines using DAVN. However, the impact of using fare adjustment alone (with standard

pick-up forecasting) is still unclear and given that not all airlines make use of virtual

bucketing or compete in markets where there is only one competitor, this thesis will

present scenarios where fare adjustment is used with other optimization models and also

in a network where there are more than one competitor. In addition, we will also be

looking at the possibility of using fare adjustment in the reservation system instead of the

revenue management system.

-

35

-

-36-

3.

SIMULATION APPROACH TO REVENUE MANAGEMENT

Competitive environments change very quickly and it is very hard to determine the

effects of a particular revenue management technique, forecaster or optimizer explicitly

in real airline environments as they are complex with far too many variables. This is why

simulation (where one can change one variable at a time and hold all others constant) is a

valuable tool as it allows for the experimentation and validation within a realistic model

of an airline environment.

Due to their static nature, analytic revenue management models entail a certain level of

simplification, hence leaving such models oftentimes inadequate for arbitrary passenger

booking behaviors or competitive actions among the airlines'. By taking a simulation

approach, a dynamic representation of revenue management practices can be modeled in

a competitive framework characterized by realistic interactions between passengers'

booking decisions and revenue management systems.

In this chapter, an overview of the Passenger Origin-Destination Simulator (PODS) that

is used to test Fare Adjustment for this thesis is provided. In addition, we will look at the

simulated air transportation network used for experimentation and the various component

modules that comprise PODS, including passenger choice, forecasting, and seat inventory

control methods.

3.1

THE PODS SIMULATION TOOL

Evolving from the Decision Window Model (DWM)61 , the Passenger Origin-Destination

Simulator (PODS) was developed at Boeing by C. Hopperstad, M. Berge, and S.

Filipowski. It simulates the environment of competing airlines and is used to study,

develop, and test new revenue management techniques. While the DWM choice model

determined passenger preferences based on the schedules, airline characteristics and a set

of other factors such as aircraft type, it omitted several important variables; namely, the

fares offered on each of the flights and the restrictions associated with each of the fares.

The PODS model has these added capabilities built in and although a fundamental part of

it replicates the schedule choice model of DWM, it is also capable of simulating

passenger choice of fare options. These capabilities make it possible to test the

competitive impacts of the implementation of a new revenue management system by one

or more of the hypothetical airlines.

60

Gorin, T., P. Belobaba. 2004. Revenue Management Performance in a Low-Fare Airline Environment:

Insights from the Passenger Origin-Destination Simulator. Journal of Revenue and PricingManagement.

Volume 3, Issue 3, pp. 215-236.

61 Boeing Airplane Company. 1997. Decision Window Path Preference Methodology Description. Seattle,

WA.

-

37 -

When PODS was first developed, it was only able to simulate a single flight leg. Now,

after much research and efforts to expand the model, it can simulate a typical airline

network of many spoke cities interconnected by a few airport hubs, in which airlines have

not only a wide variety of choices for their revenue management system but also one in

which they can vary their forecasting and optimization methodologies. In addition, the

network environment of PODS allows for passenger choice among different paths and

fare classes. Therefore, passenger demand is not modeled as an independent variable but

rather, it is treated to be interrelated and modeled using a more realistic aggregation of

many passenger level choices among competing airlines, schedules and fare products.

In PODS, passengers book or cancel their flights over 16 successive time frames. These

time frames have been user-defined to start 63 days prior to departure and end on the day

of departure. In this thesis's simulations, a time frame starts out lasting for one week, but

shrinks to two days as one approaches the date of departure in order to capture the

expected increase in booking activity as shown in Table 3-1. Passenger-related events

such as bookings and cancellations are spread randomly within each of these time frames,

while the revenue management system's major inventory control actions typically occur

at the start of each time frame.

Table 3-1: User-Defined Time Frames in PODS

Days to Departure

Time Frame

Length of Time Frame

63

56

49

42

35

31

28

24

21

17

14

10

7

_

5

_

3

_

1

_

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

(7)

(7)

(7)

(7)

(4)

(3)

(4)

(3)

(4)

(3)

(4)

(3)

(2)

(2)

(2)

(1)

0

To obtain the overall operating statistics for each simulated airline on a per day basis,

PODS averages the results obtained from the simulation. In PODS terminology, a "run"

consists of "trials" and "samples". For this study, a run (or a single simulation) is the

average of five independent trials and each trial is the iterative result of 600 samples (to

ensure statistical significance of a simulation's results), with each sample representing a

single departure day.

Data for the first sample of each trial are defined arbitrarily by the user. These user inputs

are gradually replaced with calculated values from simulation (with each sample having

some degree of correlation to the next sample for they are used as historical data) and the

first 200 samples of each trial are discarded. Thus, the results of a 600 sample trial are

based only on the last 400 samples, and every PODS run is actually the averaged result of

2,000 samples.

Fundamentally, PODS is the simulation of the interactions between passengers and

airlines (See Figure 3-1). On the passengers side, PODS simulates passengers are who

looking to travel in a specific OD market and trying to make their decisions based on a

variety of factors such as airlines, itineraries and fare classes. This contributes to the

demand side of the equation and booking information obtained on this side is passed over

the fence to the airlines.

-38-

Revenue Management

System

Passenger Choice Model

.- -- ~

Demand

Decision

Window

Seat Allocation

Optimizer

I

Generation

Model

Path/Class

,fl

-

Availability

Current

Bookings

Passenger

-Characteristic

Future

Bookings

Forecaster

Passenger

Choice Set

Path/Class

Bookings and

Cancellations

Update

Historical

Bookings

Historical Booking

Database

Passenger

Decision

Figure 3-1: PODS Structure

The airline side of the simulator on the other hand, consists of a third generation revenue

management system (as described in Section 2.1) that is used by airlines that supply air

travel offerings to customers. Using both the current and historical booking information,

the airlines determine the number of seats to offer for each of the fare classes on each OD

market. This information is then passed back over the fence to the passengers to influence

the demand patterns.

3.1.1

Passenger Choice Model

The success of any given revenue management method is dependent on its ability to

maximize revenues based on the behavior of passengers. In PODS, these behaviors are

governed by the Passenger Choice Model, which consists of four sequential steps:

Demand Generation, Assignment of Passenger Characteristics, Definition of Passenger

Choice Set and finally a specific Passenger Decision (see Figure 3-1). This section

provides a general overview of the Passenger Choice Model. A more comprehensive

discussion of the PODS Passenger Choice Model, including its assumptions, logic, and

ultimate validation can be found in Carrier 2 .

Carrier, E. 2003. Modeling Airline Passenger Choice: Passenger Preference for Schedule in the