Document 10478497

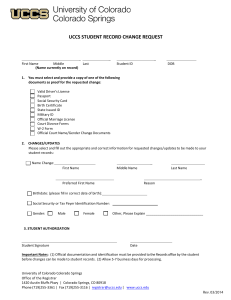

advertisement