Participatory Autocracy: Private Entrepreneurs,

Legislatures, and Property Protection in China

ARCHIVES

by

M ASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY~

Yue Hou

B.A. Economics and Mathematics

DEC 0 7 2015

Grinnell College, 2009

LIBRARIES

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE

OF

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

AT THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

SEPTEMBER 2015

@ 2015 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved

Signature of Author.

Signature redacted . .

Department of Political Science

Certified by .......

Signature redacted

August27, 2015

Lily L. Tsai

Associate Professor of Political Science

Accepted by ....

Signature redacted

Thesis Supervisor

Ben Ross Schneider

Ford International Professor of Political Science

Chair, Graduate Program Committee

2

Participatory Autocracy:

Private Entrepreneurs, Legislatures, and Property Protection in China

by

Yue Hou

Submitted to the Department of Political Science on August 27, 2015

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science

ABSTRACT

This dissertation addresses the puzzle of why individuals in authoritarian systems

seek office in formal institutions, which are often dismissed as weak and ineffective. I

argue that individuals seek office mainly to protect their property from government

expropriation in China. In contrast to prior work, I argue that instead of being

passive takers of existing institutional arrangements, private entrepreneurs in China

actively seek opportunities within formal institutions to advance their interests. By

holding seats in local legislatures, entrepreneurs signal to local bureaucrats that they

have access to higher-level government officials to report illicit predatory behavior.

This signal, in turn, deters local officials from demanding bribes, ad hoc taxes, and

other types of informal payments.

I deploy both qualitative and quantitative methods to support the argument.

First, to understand state-business relations in China, I conducted 106 in-depth interviews with private entrepreneurs, government officials, and local scholars in five

provinces during 16 months of fieldwork. I show that even while government expropriation is an endemic problem, private entrepreneurs who are also legislative

officeholders are less likely to experience severe expropriation. Second, using a nationally representative survey of private entrepreneurs, I quantitatively show that

entrepreneurs who have seats in the local legislatures on average spend 25 percent

less on informal payments to local officials compared to entrepreneurs without such

a political status.

To investigate the causal link between formal office and protection of property,

I conducted field experiments on Chinese bureaucrats to understand how local bureaucracies respond to constituents with connections to formal institutions. These

experiments involved directly contacting officials to examine how they respond to

realistic messages from citizens. Using an experimental manipulation, I demonstrate

3

that Chinese bureaucrats are 35 percent more likely to respond to a constituent with

connections to formal institutions.

These findings challenge prominent theories of authoritarian politics, which see

authoritarian institutions as instruments to arrange power sharing, rent distribution,

or information collection. Adopting an "institution as resource" perspective, I show

that within authoritarian institutions, entrepreneurial actors can seek opportunities

to advance their interests and improve their well-being through formal means, even

when these formal institutions are relatively weak.

Thesis Supervisor: Lily L. Tsai

Title: Associate Professor of Political Science

4

To my family: Zeng Xuhua, Hou Yunlong, Zhu Zaixi, Tang Guoquan,

Tang Meirong, and Hou Jialin

5

6

.................................................

Acknowledgments

-

I have grown tremendously during my six years at MIT and have accumulated a

large debt of gratitude along the way.

First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Lily Tsai,

my committee chair. Lily has provided unparalleled guidance, encouragement, and

support since the moment she called me and welcomed me to the program. She

took me to China my first summer at MIT and I learned from her how to conduct

careful fieldwork and to understand my own country through an analytical lens. She

has believed in me and in this project from the beginning and has been my closest

reader, providing valuable comments and moral support throughout. I cannot thank

her enough for her mentorship and support. David Singer was my advisor for the

first two years and - despite my (hopefully temporary) "defection" from IPE

he has continued to serve as an advisor and a supporter. His insights helped me

frame this dissertation and keep it relevant for a greater audience. Yasheng Huang

is an authoritative figure in Chinese political economy. He not only serves as a

sounding board for my arguments, but also generously provided me with the private

entrepreneur survey data, which constitutes a main empirical component of my

dissertation. Danny Hidalgo joined the committee last, but his contribution has

nevertheless been essential. His office is next door to mine and whenever I have had

a method question I would go ask him. He has constantly given me new ideas to

test and taught me to approach problems with rigorous design. I will always see my

advisors as role models; I will aspire to bring their levels of rigor and depth to my

own scholarship and to become the kind of teacher to my students that they have

been to me.

I would like to thank many other faculty members in the department for their

mentorship. Adam Berinsky and Teppei Yamamoto are also my go-to people for

advice and feedback - I go to them so often that many think that they are also on

my committee. Rich Nielsen and Lucas Stanczyk have also been frequent sources of

guidance. Suzanne Berger, Kathy Thelen, and Fotini Christia have served as role

models of great female scholars, and they have all been extremely generous with their

time and advice. I would also like to express my gratitude to Gina Bateson, Andrea

Campbell, Devin Caughey, Taylor Fravel, Jens Hainmueller, In Song Kim, Chap

Lawson, Evan Lieberman, Rick Locke, Melissa Nobles, Mike Piori, Dan Posner, Ben

Schneider, Ed Steinfeld, Charles Stewart, and Chris Warshaw.

I could not have asked for a better cohort of colleagues: Chris Clary, Jeremy Ferwerda, Chad Hazlett, David Hyun-Saeng, Nicholas Miller, Krista Loose, and Joseph

Torigian. Not only are they all talented political scientists, they have provided

good humor throughout the journey. I would also like to thank Greg Distelhorst,

Yiqing Xu, Laura Chirot, Martin Alonso, Elizabeth Dekeyser, James Dunham, Dan

7

de Kadt, Dean Knox, Jia-chuan Kwok, Elisa Heaps, Joyce Hodel, Dian Li, Akshay Mangla, Michele Margolis, Ben Morse, Renato Oliveira, Tom O'Grady, Kai

Quek, Blair Reed, Tesalia Rizzo, Leah Rosenzweig, Mike Sances, Kyoung Shin,

Leah Stokes, Andreas Wiedemann, Weihuang Wong, and Ketian Zhang for their

camaraderie and insights.

I thank Paige Bollen, Janine Claysmith, Pam Clements, Maria DiMauro, Diana

Gallagher, Fuquan Gao, Daniel Guenther, Paula Kreutzer, Scott Schnyer, My Seppo,

Tobie Weiner, and Susan Twarog for their friendship and help.

I am very grateful to my Grinnell professors, especially Eliza Willis, Janet Seiz,

and Emily and Tom Moore for encouraging me to pursue political science. I thank

Don and Doris Sundell for having provided me with a loving home away from home.

Outside the department, I have received comments and support from Daron Acemoglu, Oscar Almen, Yuen Yuen Ang, Lisa Blaydes, John Carey, Ling Chen, Shuo

Chen, Bruce Dickson, Mary Gallagher, Xiang Gao, Jennifer Ghandi, Jingkai He,

Junzhi He, Wenkai He, Yusaku Horiuchi, Jeremy Horowitz, Biliang Hu, Kyle Jaros,

Junyan Jiang, Gary King, Daniel Koss, James Kung, Pierre Landry, Horacio Larreguy, Xiaojun Li, Hanzhang Liu, Lizhi Liu, Peter Lorentzen, Hao Liu, Xiaobo

Lu, Chris Lucas, Melanie Manion, Tianguang Meng, Gwyneth McClendon, Daniel

Moskowtiz, Ben Nobles, Ben Olken, Steve Oliver, Jennifer Pan, Liz Perry, Rahul

Sagar, Tony Saich, Paul Schuler, Niloufer Siddiqui, Rory Truex, Jeremy Wallace,

Erik H. Wang, Yanbo Wang, Yuhua Wang, Changdong Zhang, Dong Zhang, and

Shukai Zhao.

I am grateful for the financial support of the MIT Political Science Department,

MIT Center of International Studies, and the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for

International Scholarly Exchange Doctoral Grant. I thank Jennifer Morales for

copyediting and Yao Yao of Zhejiang University for her research assistance.

I have accumulated a group of talented and supportive friends at MIT and Cambridge, in particular I thank Wanli Fang, Pian Shu, Lan Wei, Yushan Jiang, Yuan

Xiao, Steve Voinea, Lilei Xu, Yang Sun, Xitong Li, Luo Zuo, Kexin Zheng, Song Lin,

Jingsi Xu, Taiyi Sun, Zhifei Ge, Lupeng Liu, Yang Du, Qian Liu, Dimitrios Tzeranis,

Le Cong, Zawadi Lemayian, Yang Liu, and especially Hang Chen for being there for

me.

I am also fortunate to have maintained close contact with my "older" network

of friends, who are now in many different parts of the world but nevertheless have

continued to support me and inspire me, especially Deng Dui, Song Zhiyuan, Le Yue,

Li An, Li Lemin, Long Fangzhou, Wu Xuan, Zhao Wei, Zhou Mi, Duan Dawei, Liang

Yi, Wutyi Ang, Phoebe Leung, Haleema Shehryar, Wang Nan, Natalie Michelson,

Steven Parker, and the Rees family.

Last but not least, I thank my wonderful family. My aunts, uncles, and cousins

Tang Lirong, Tang Yuehua, Hou Huazhong, Hou Xiaoyu, Hou Xiaoli, Wang Xing, Li

Qian, Hou Weixin, and Hou Tian, most of whom are living in Hunan, have always

welcomed me when I am home and taken care of my parents and grandparents

while I am away. I own them a tremendous debt. My grandparents, Zeng Xuhua,

Hou Yunlong, Zhu Zaixi, and Tang Guoquan, have given me endless care and love.

8

My grandpa Yunlong, who encouraged me to watch the news while having dinner

with him starting about when I was six, was the earliest influence on my interest

in political and social issues. Finally I thank my parents, Tang Meirong and Hou

Jialin, for their unconditional love, support, and encouragement. Even while raising

me, they have managed to accomplish many enormous achievements in their own

careers. Because of the work they do, they have provided me with great insights on

the Chinese economy and are always interested in learning about my work. Their

diligence, curiosity, and open-mindedness have made me who I am. This dissertation

is dedicated to my family.

9

Contents

Abstract

3

Acknowledgments

7

Chapter 1 Introduction

11

Chapter 2 China's Legislative System

46

Chapter 3 Motivations to Run

72

Chapter 4 Protection from Predation

124

Chapter 5 Legislator Status as a Political Capital Signal

155

Chapter 6 Conclusion

195

Bibliography

209

10

Chapter 1

Introduction

"The fundamental economic dilemma of a political system is this: A government that

is strong enough to protect property and enforce contracts is also strong enough to

confiscate the wealth of its citizens." (Weingast 1993)

A small Chinese city named Hengyang, located in the central province

of Hunan, made national news in early 2013.

A bribery report was

leaked through a China Central Television (CCTV) reporter's microblog

account: A Hunan provincial legislator, Zuo Jianguo, chairman of the

board of a real estate company, was accused of having bribed her way into

the provincial legislature (the provincial people's congress) by buying

votes from prefectural lawmakers in Hengyang. The Chinese legislatures

are called people's congress, which run both at the national and subnational level. Chinese legislators are called people's congress deputies.

In China, citizens directly elect legislators in their county and district.

All higher-level legislators are elected by the corresponding lower-level

legislators. For example, county and district legislators elect prefectural

legislators, who then elect provincial legislators.

Provincial legislators

then elect national legislators (National People's Congress deputies). It

was reported that by buying votes from each of the county-level legisla-

11

tors at the cost of 3,000 yuan per person, Zuo secured a prefectural seat

at the total price of 700,000 yuan.1 In the same year, through buying

votes from each and every prefectural legislator, she further secured a

seat at the provincial congress assembly. The total amount spent bribing these voters came to an alarming three million yuan.2 Interestingly,

the whistle-blower, Huang Yubiao, who tipped off the CCTV reporter,

was himself a provincial candidate. He also bribed the prefecture-level

voters, but failed to get a seat in the provincial assembly. 3

It turned out that Zuo and Huang were not the only candidates who bribed their

local legislators to get elected to the higher-level legislature.

After receiving the

bribery report, the Hunan Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Committee (the Chinese Communist Party Committee will be referred as "the Party Committee," hereafter) Discipline Commission conducted a thorough investigation into other Hengyang

legislators, uncovering some astonishing facts: In 2013, 56 of Hengyang's 76 deputies

to the Hunan provincial people's congress secured their positions by bribing 518 local people's congress members from Hengyang. In total, these candidates spent 110

million yuan in bribes to deputies and relevant staffers in the Hengyang people's

congress office. As a result of the investigation, 56 provincial legislators have been

removed and the 518 Hengyang prefectural people's congress deputies involved have

resigned. 4

Interestingly, among the initial 93 Hengyang provincial candidates, 44 were private entrepreneurs. Among the 15 deputies whose seats were originally designated

1 One U.S. Dollar

-

6.06 Chinese yuan in 2013.

2 For a news report in Chinese, see http://goo.gl/osxUJr

3 Another Chinese news report: ittp://news.sina.con.cn/c/2014-01-26/031029345758.shtnl

4 Source(Chinese): http://usa.chinadaily.con.cn/epaper/2013-12,/30/content_17205118.htm

12

'

utIr

Bl

1111911MIMM~I

WillillUllMllMIMililliinillililMIMilli

llW

flliT

li'11

'

for "industrial workers," all of them turned out to be private entrepreneurs. Of the 13

deputy seats designated for "peasant candidates," only three were real "peasants" and

the remaining 10 were also private entrepreneurs. An internal report accused these

entrepreneur candidates of having started the practice of vote-buying, after which

other candidates had to follow suit (Internal Report, 2014). Among the 56 candidates ultimately elected as provincial legislators, 32 were private entrepreneurs .5

Why do private entrepreneurs 6 seek office in authoritarian legislatures, where these

formal institutions are often dismissed as weak and ineffective in interest representation or influencing policy? If the costs of getting into these legislatures are so

high, what are the benefits of holding a seat? Existing theories share a state-centric

perspective: Autocrats design the structure of the system as well as the payoffs

to each player. Representatives and other actors simply cooperate and obtain the

prearranged payoffs accordingly. In contrast to the existing literature, I show that

representatives in authoritarian institutions are more than passive rule-followers and

"institution takers." Instead, by joining formal political institutions such as legislatures, individuals actively seek opportunities to advance their interests.

This dissertation studies the Chinese legislatures.

I argue that individuals or,

more specifically, private entrepreneurs seek office in Chinese legislatures mainly to

protect their property from government expropriation. Becoming a legislator gives a

private entrepreneur access to higher-level government channels for reporting illicit

predation and violations of property rights by lower-level officials. Even if he7 does

not use this access, the entrepreneur uses his legislator status to "flex his muscles"

5 Source(Chinese): http://www.360doc.com/content/13/1229/13/6791042_340982375.shtml

6 Following Lardy (2014, 4), private enterprises in this dissertation refer to the universe of household businesses, registered private companies, and firms in which the majority or dominant owner

is private. For a more comprehensive discussion on the ownership structure of Chinese firms and

definition of the private sector, see Dickson (2008, Chapter 2); Huang (2008, Chapter 1); Pearson

(1997, 16-18); and Tsai (2007, 71).

7

I use the male pronoun in all instances, because the majority of private entrepreneurs and

legislators are male.

13

to bureaucrats and send a strong and credible signal that he has access to a highlevel political network. Such a signal presents a credible threat and therefore deters

predatory local officials. Here, Chinese entrepreneurs do not seek legislative office

to make laws or to influence policies; rather, they use their formal political status

to protect property. Such privileges, which might not be intentionally designed by

the upper-level autocrats, are well-aligned with the incentives of the ruling elite.

Holding political office as a strategy for shielding property from expropriation is

by no means China-specific. During Suharto's authoritarian rule in Indonesia, high

government positions were used as protection rackets (Winters 2011). In Mubarak's

Egypt, businessmen competed for parliamentary seats, which grant immunity from

charges of corruption (Blaydes 2011).

During his dictatorship, Porfirio Diaz in

Mexico encouraged regional political leaders to go into business and to turn potential

political enemies into third-party enforcers of the individualistic property rights

system (Haber, Razo and Maurer 2003). Even in Singapore, a state reputed to have

a highly impersonal system of law, exceptional cases exist in which political leaders

have been exempted by the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau, so that their

wealth can be remain untouched (Francis 2006).

This project is in conversation with two important bodies of literature in comparative politics. First, it challenges prominent theories of authoritarian institutions,

the majority of which share a state-centric perspective in explaining the functioning

of authoritarian institutions and the incentive structure within them. The theory of

"co-optation" argues that autocrats set up these institutions to identify and co-opt

members of the opposition (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003; Gandhi and Przeworski

2006; Gandhi and Przeworski 2007; Gandhi 2008; Malesky and Schuler 2010). The

theory of "power-sharing" suggests that these institutions are designed to facilitate

monitoring and power-sharing among the ruling elite (Magaloni 2008; Myerson 2008)

14

and sometimes to bribe and split the opposition (Wright 2008). The theory of "information flow" proposes that authoritarian institutional settings enable information

flow between citizens and political leaders, and thus enable responsive policymaking

(Brownlee 2007; Manion 2008; Simpster 2014; Schuler 2014). I challenge these statecentric approaches, where institutions were created to perfectly serve the interests

they advance at later periods. Instead, similar to Thelen (2004), I see institutions as

"resources and instruments," which entrepreneurial actors "gradually adapt to their

purposes." The opportunities these actors discover, therefore, are not necessarily

part of the initial institutional arrangement.

Second, this dissertation qualifies an emerging view that individual firms can

strengthen property security through formal means, even when these formal institutions are relatively weak. Prevailing explanations of property security formation

treat the state as the primary enforcer of property rights (e.g., Acemoglu and Johnson 2003; Levi 1988; Ostrom 1990).

In their theories, firms are mere policy and

institutional takers, and they usually resort to informal means when formal institutions are weak or non-functioning. Recent works on post-Soviet economies give more

weight to individual firms in explaining property security formation in transitioning

economies. For instance, Markus (2012) discusses bottom-up strategies (e.g., making alliances with other shareholders) that firms in Russia and Ukraine use to secure

property rights; Gans-Morse (2012) documents occasions and identifies conditions

when Russian firms use formal institutions to solve property disputes. My argument is consistent with their firm-centric approach to understand property security

formation as a bottom-up process. In contrast to Jensen, Malesky and Weymouth

(2013) who argue that authoritarian legislatures are too weak to restrain dictators or

single parties from committing expropriations, I show that individuals can actually

use authoritarian institutions to deter local expropriation.

15

The remainder of the chapter is structured as follows.

The next section sur-

veys literature on the role of authoritarian legislatures. I then present the case for

my theory regarding Chinese entrepreneurs' strategy to protect their property from

expropriation, followed by a discussion on the observable implications.

The next

section dives into the literature on property protection in transitional economies

and discusses how my argument complements this body of literature. The following section discusses how the theory compares with other possible explanations on

Chinese entrepreneurs' political participation. The chapter ends with a description

of data I will use in the dissertation.

The Role of Authoritarian Legislatures

Before elaborating my argument, I first review major schools of thought that theorize

authoritarian legislatures and discuss why existing theories remain inadequate in

explaining the case of Chinese legislatures and the behavior of the participants,

especially that of the private entrepreneurs.

Earlier studies on authoritarian institutions see authoritarian legislatures as "rubberstamp" institutions that have little impact on policy.

They are created to fulfill

demonstration purposes. Rustow (1985) sees legislative elections as a merely "political tactic" that "payfs] homage to virtue" in the authoritarian Middle East. Magaloni

(2006) argues that elections help the PRI, Mexico's dominant party, to establish an

"image of invincibility," deterring potential opponents from entering the political

market.

In the same vein, Geddes (2008) argues that rubber-stamp parties and

elections remind potential opponents of the difficulty of overthrowing the regime

and thus serve the function of deterring coups.

A rich body of literature suggests that authoritarian institutions co-opt opposition

16

.W&__

or potential opposition by making policy concessions and by sharing power. Gandhi

and Przeworski (2006, 2007) suggest that authoritarian legislatures facilitate policy

concessions by providing a forum in which "demands can be revealed and agreements can be hammered out." Authoritarian legislatures are especially ideal for

policy concession because they "allow for an environment of controlled bargaining"

(Gandhi 2008, 78). Focusing on the institution's role in alleviating commitment and

monitoring problems, Boix and Svolik (2013) and Svolik (2009) argue that dictators

make credible power-sharing commitments to the ruling elite through legislatures

and other authoritarian institutions to solicit support and to enhance authoritarian survival.

Similarly, Magaloni (2008) argues that political organizations make

possible intertemporal power-sharing deals between dictators and their allies.

Dictators can also co-opt potential elites through legislatures by sharing rents, the

forms of which include monetary rewards, perks and privileges (Gandhi and Przeworski 2006). In Egypt, parliamentarians receive loans without interest or collateral,

and even immunity from criminal prosecution (Blaydes 2011; Kienle 2004). In Jordan, parliamentarians can distribute discretionary funds as they see fit in responding

to constituents' and their own needs (Lust-Okar 2006a). In China, national legislators enjoy better access to information and protection from corruption investigation

(Truex 2014).

According to a 2013 survey of 100 Chinese private entrepreneurs,

41% believe that entrepreneurs who are legislators have easier access to government

contracts and policy information. 8

An emerging literature views authoritarian legislatures as an important source of

information on regime stability, public opinion and policy implementation. Compared to democratic regimes, autocrats face greater challenges in collecting inforination about the behavior of their local agents, public approval of policies, and

8 This survey was conducted by a private company, which asked to be anonymous.

17

sources of discontent

(Distelhorst and Hou 2015; Lorentzen 2013). Autocrats re-

spond to these informational challenges with a variety of information-gathering institutions including media freedom (Distelhorst 2013; Egorov, Guriev and Sonin

2009; Lorentzen 2014), technological and human surveillance (Morozov 2012), public opinion polling (Henn 1998), constituency services (Distelhorst and Hou 2015),

and electoral contests. Magaloni (2006) argues that elections in Mexico not only

communicate information about the regime's strength and discourage potential divisions within the ruling party, but also about supporters and opponents of the

regime. Schuler's observation (2014) of the Vietnam legislatures reveals that the

Vietnamese Communist Party allows discussion and debate on issue areas where

responsibility for policy implementation is outside of party control. By exercising

agenda control, the Communist Party collects information on policy implementation

while making sure its authority remains unchallenged. Similarly, scholars of Chinese

legislatures argue that the Chinese Communist Party uses the legislative system to

collect information on public opinion and citizen preferences (e.g., Manion 2008;

Manion 2014; O'Brien 1994a; Truex 2013).

The Argument

Although my argument builds on a number of important scholarly works oil authoritarian legislatures, it stands in direct contrast to these explanations in terms

of our views on institutions. Existing views treat institutions as tools of the state:

Authoritarian legislatures are institutional arrangements for power-sharing, distribution of rents, or information collection. These institutions are well-designed to fulfill

the purposes of autocrats and to anticipate and advance various parties' interests.

These views are essentially functionalist approaches that try to explain the functions

18

of authoritarian legislatures ex post. In adopting this approach, they largely ignore

the processes of search, innovation and negotiation whereby entrepreneurial actors

discover new channels, usually within these institutions, to advance their interests

(Knight 1995).

Instead of viewing institutions as tools of the state, I borrow the perspective of

"institutions as resources," an approach which treats institutions as "instruments

that actors gradually adapt to their purposes and in which they become invested

only after they have acconmodated their practice to them" (Thelen 2004). In their

studies on advanced democracies, institutions are resources that provide opportunities for particular types of actions, especially for collective action (Hall and Thelen

2009). Authoritarian institutions allow a different set of opportunities for particular types of actions. Collective action is not likely to be welcomed (King, Pan and

Roberts 2013), yet entrepreneurial actors can seek opportunities to advance their

interests and improve their well-being through a variety of institutional channels, as

long as the outcomes are compatible with the incentives of the ruling autocrats.

The core argument is that the parliamentary system in China is not merely a static

and functional response of an authoritarian regime to maintain political stability

and legitimacy.

Instead, it provides entrepreneurial actors with opportunities to

advance their own interests, so long as the realization of interests is well-aligned

with the incentives of the ruling elite. In the case of China, private entrepreneurs,

who operate their businesses in an environment where property rights are largely

unprotected, seek office in the local legislatures to protect their property.

The

status of a local legislator sends a clear and credible signal of one's strong political

network with upper-level officials, and this signal deters predatory behavior by lowerlevel bureaucrats, who are afraid of retribution or punishment from the legislator's

political network.

The ruling elite is aware of local expropriation but does not

19

tolerate unconstrained expropriation. Therefore, entrepreneurs' action of obtaining

legislative office to deter expropriation, although not necessarily created by top-down

design, is incentive-compatible with the motivations of the ruling elite.

In the Chinese legislatures, the interaction between a number of important societal actors is complex.

To make sense of the complex system, it is imperative

to understand the preferences of each actor. I focus on the relationship between

three main actors in the Chinese authoritarian system: the higher-level officials, the

lower-level bureaucrats, and the entrepreneur deputies. Other relevant actors will

be discussed at the end of this section.

Higher-Level Officials

Here, higher-level officials is a broad category, and the term "higher-level" corresponds to the group of actors -

"lower-level" bureaucrats -

which I discuss next.

These higher-level officials include the ruling elite in Beijing who exercise the most

power and establish the rules of the game. The group includes the General Secretary of the Communist Party/the President of the PRC, his peers at the Politburo

Standing Committee, and a small group of political and business elite that surround

them. Consistent with major theories on authoritarianism, this project assumes that

the primary interest of the ruling elite is to stay in power. To consolidate power,

autocrats use legislative institutions to collect information and to share rents with

other elites and potential opposition.

Legislatures are an important source of information for the ruling elite. With the

absence of democratic elections, which reveal citizen preferences, autocratic leaders

struggle to gather information regarding public approval of policy implementation,

as well as the behavior of their local agents (Lorentzen 2013). To respond to this information constraint, non-democratic regimes collect information through a variety

of alternative channels. My argument aligns with the view that authoritarian elec-

20

'k

...............

.

WN"",

toral contests provide autocrats with information about the society and the bureaucracy (Blaydes 2011; Magaloni 2006). Through legislative plenums and legislative

proposals, autocrats not only acquire information on public opinion, but also on the

behavior of lower-level bureaucrats (Birney 2007). In the case of China, higher-level

autocrats have limited information on the behavior of lower-level bureaucrats, but

the system provides incentives for other actors to collect information and to report

back.

Apart from information collection, the ruling elite also uses legislatures to share

spoils with other elites. For instance, Truex (2014) carefully documents the "return

to office" to members of China's national people's congress and estimates that companies with a national legislator would enjoy an average of 1.5 to 2 extra percentage

points in returns and a 3 to 4 percentage point boost in operating profit margin,

compared with similar companies without a top executive as a national legislator.

Many scholars have argued that authoritarian legislatures can be used as a platform

to arrange policy concession (e.g., Gandhi 2008), but the Chinese legislatures do not

seem to serve such a function for the ruling elite because the legislative function of

local legislatures is quite weak.

The dissertation does not study the origins of authoritarian legislatures, but it

contrasts major theories of authoritarianism in understanding the decisions of the

ruling elites. Autocrats might have created semi-democratic institutions for a variety

of purposes, and other benefits might evolve over time. In existing theories, autocrats

almost always maximize their utility with institutions of their creation, and other

actors in the system simply comply. Rarely do scholars study the institutional byproducts created by actors other than the ruling elite.9 Property security is one such

9

Blaydes (2011) briefly mentions that there might exist "endogenous by-products" of institutional

equilibrium that could potentially undermine the stability of regime, but there is no further

elaboration.

21

by-product of Chinese local legislatures that is exploited by private entrepreneurs.

It would be a stretch to argue that property security of private entrepreneurs is

a major concern for the Chinese ruling elite. Quite to the opposite, I would agree

with Levi's assessment that most rulers are predatory because they "design property

rights and policies meant to maximize their own personal power and wealth" (Levi

1981). Thus, the only conclusion I can make here is that the individualistic strategy

of property protection exercised by private entrepreneurs is incentive-compatible

with the ruling elite. Wedeen (1999) characterizes unintentional decisions made by

autocrats as "strategies without a strategist;" here, I go one step further and argue

that autocrats can even be non-strategic, allowing other actors to exploit institutions

for multiple purposes.

Besides the ruling elite, higher-level officials in this model also include the superiors of the bureaucrats who work in local government offices and agencies. Here, "superior" and "higher-level" are relative terms. For example, when I study county-level

tax collectors, their higher-level officials would be their direct superiors level tax bureau heads, and their indirect superior -

county-

officials working at the prefec-

tural, provincial, and national tax bureaus. However, when I study prefectural-level

tax collectors, the very same "higher-level" prefectural tax bureau officials become

"lower-level bureaucrats" in this case, and their higher-level superiors include their

direct superiors -

prefectural tax bureau heads, and indirect superiors -

officials

working at the provincial and national tax bureaus.

These individuals are the principals of their lower-level superiors.

Principals

(higher-level officials) assign agents (lower-level bureaucrats) specific tasks and evaluate these agents based on a performance standard. Just like any principal-agent

relationship, principals cannot always successfully monitor the behaviors of their

agents and they suffer from problems of hidden information and hidden actions. In

.............

, ""T

this context, a main concern of these principals is that lower-level agents sometimes

exploit their offices for private means.10 These higher-level officials, aware of the

problem, have developed a toolkit of methods to monitor and evaluate their agents

(e.g., Lu and Landry 2014). Local legislatures provide higher-level officials an additional source of information on the behavior of their agents: a fixed number of

seats are designated to local businessmen at each level of local people's congresses,

and these local legislator-entrepreneurs provide reliable and important information

on how local bureaucrats do their jobs.

Local legislatures also provide a formal means for higher-level officials to befriend

local entrepreneurs who, as we will discuss below, are established and successful

in the local economy. There are numerous reasons local governments and officials

need to nurture friendly relationships with local business elites. Local businesses,

as Kennedy points out, are "central to accomplishing government objectives such

as a growing economy, stable prices, high employment, and expanding tax receipts"

(Kennedy 2009). In resource-scarce areas, business elites are especially important

as sponsors for public projects and the functioning of local administration (Lu 2000;

Sun, Zhu and Wu 2014). Patron-client ties are also built based on personal connections. Kennedy observes that "[olfficials provide entrepreneurs access to scarce

goods, credit, government and overseas markets, and protection from onerous regulations. Entrepreneurs, in return, provide officials with payoffs and gifts, employment,

and business partnerships" (Kennedy 2005, 10). Local political and business elites

make connections through organized lectures, parties, meetings, and get-togethers

organized by various government bureaus, associations, and individual business elites

(Wank 1996). The nature of some of these events might be informal. On the other

10 How they do so will be discussed in the subsequent section.

23

hand, conversations and friendships nurtured through plenary sessions, meetings,

visits, tours, and other events related to local people's congresses provide opportunities for formal business-government interactions (Sun, Zhu and Wu 2014). Minxin

Pei, a political scientist and a critic of the Chinese government, describes the predatory and corrupt nature of the ruling elites in the following way:

The most lethal strain of leadership degeneration is escalating predation

among the ruling elites. The most visible symptom is corruption, but

the cause is intrinsic to autocratic rule. Typically, first-generation revolutionaries have a strong emotional and ideological attachment to certain

ideals, however misguided they may be. But the post-revolutionary elites

are ideologically cynical and opportunistic. They view their work for the

regime merely as a form of investment. And, like investors, they seek

ever-higher returns.

As each preceding generation of rulers cashes in its illicit gains from

holding power, the successors are motivated by both the desire to loot

even more and the fear that there may not be much left by the time

they get their turn at the trough. This is the underlying dynamic driving corruption in China today. In fact, the consequences of leadership

degeneration are easy to see: faltering economic dynamism and growth,

rising social tensions, and loss of government credibility (Pei, 2012).

Lower-Level Bureaucrats

Lower-level bureaucrats are the agents of their higher-level principals.

In this

project, lower-level bureaucrats are subnational government bureaucrats who interact with local businesses across all relevant agencies. These bureaucrats come from

local taxation bureaus, administrations for industry and commerce, environmental

24

protection agencies, administrations of work safety and coal mine safety, administrations of quality supervision, inspection and quarantine, the police bureau, and other

local agencies. It is estimated that 2.5% of China's local population is employed in

the local public sector, a proportion two times greater than the global mean of 1.1%

(Ang 2012). Among these local-level civil servants, 61.8% frequently or occasionally

interact with local businesses (Hou, Meng and Yang 2014).

In this stylized argument, I assume that these bureaucrats have two main objectives in mind: to get promoted and to extract rents when possible." The "grabbing

hand" nature of local bureaucrats is a common assumption in the public choice literature (e.g., Krueger 1974; Olson 1965; Shleifer and Vishny 2002, Chapter 1). In

China, there certainly exist a significant number of local bureaucrats who are publicly spirited and serve their constituents. But at the same time, many bureaucrats

are exploitative and would extract rent from local businesses whenever possible.

Many argue that, receiving a comparatively low salary, Chinese civil servants naturally seek moonlighting opportunities and to engage in inappropriate practices often

associated with corruption (Chan and Ma 2011; Lu 2000). These bureaucrats extract rents from local businesses by imposing informal taxes, fees and fines through

ad hoc investigations. In the Chinese context, these informal payments are often

called tanpai, and I hereafter use the terms extraction, predation, and expropriation

as interchangeable equivalents.

These informal payments range from "protection

fees" paid to local bureaus, to "pre-paid" tax collected by local taxation bureaus,

and from "forced donations" to, for example, build a new road in the village to ad

hoc fines and payments. Writing on Chinese private entrepreneurs, Tsai observed

that "[iln any given week, the typical factory owner may be approached by dozens of

" 1On this assumption, one might object that some Chinese local bureaucrats could be publicly

spirited, pursuing justice and acting according to moral and ideological principles, even at some

cost to their wealth or career prospects. In those cases, we would observe a very low level of

extraction.

25

different agencies requesting seemingly random user charges, surcharges, and contributions for local projects" (Tsai 2004). Income from extraction could either go

to local governments' budgets to support legitimate provision of public goods, or it

could go to bureaucrats' pockets (Tsai 2004). It is perhaps more justified to extract

local business if the extracted income goes to public projects, but from the perspective of entrepreneurs, extraction is undesirable and is considered an infringement on

their property.

Ang, a scholar of the Chinese bureaucracy, provides institutional explanations in

understanding the prevalence of predation at the local level:

... China's fast-growing economy has not been governed by a purely

salaried civil service. Instead, Chinese bureaucracies still remain partially prebendal; at every level of government, each office systematically

appropriates authority to generate income for itself. Such a bureaucratic

form normally invites predation and hinders capitalism. ... (Ang 2009)

Local bureaucrats want to extract rents, but they do not want to get caught preying

on businesses. They are more likely to get caught or be reported if they prey on

individuals who have access to the bureaucrats' principals. Some bureaucrats might

have more information than others about the local elite network, but in general, these

low-level officials have limited information about each local entrepreneur: Who is

politically connected? Who has friends in the governments who can protect him?

Facing information constraints, low-level bureaucrats usually find it costly and,

many times, impossible to identify each and every piece of information regarding

elite connections. In this limited information environment, bureaucrats make careful

decisions about whom to extract rent from. A local people's congress membership is

a strong and clear signal of one's local political network. An entrepreneur who is a

legislative deputy signals his access to the upper-level officials and an elite network

26

he obtains through participating in the legislature. Receiving this signal, a low-level

bureaucrat is likely to avoid extracting the business, for fear that the legislatorentrepreneur might report to the upper-level officials.

EntrepreneurLegislators

Business elite is the second largest group represented in the Chinese local legislatures. A good portion of these business elites come from the state-owned sector,

but the private sector is becoming increasingly more represented in Chinese people's

congresses (Li, Meng and Zhang 2006). Business elites who have a seat in the legislatures are fundamentally different from those who do not: Legislators' firms are

usually the better performers in the local political economy and in their industry.

They tend to have higher returns, operating profit margins, and revenues (Truex

2014).

Getting a seat in the local legislatures is a complex and competitive process. According to the 2010 Electoral Law, county- and district-level legislators are directly

elected by their local constituents, and legislators at the prefectural, provincial,

and national levels are elected by their lower-level legislatures. The total number of

seats at each level is stipulated in the Electoral Law. A temporary Party-led election

committee, the majority of whose members come from the local Communist Party

committee, is formed prior to elections to manage the electoral process. To ensure

broad representation, the election committee assigns strict quotas specifying that

each congress should have a certain proportion of government and party officials,

entrepreneurs, peasants, intellectuals, and deputies representing other occupations

(O'Brien and Li 1993). According to the Electoral Law, the ballot must list 1.33 to

2 candidates per legislative seat (Manion 2014), and the election committee decides

on the final number.

27

Thus, if a private entrepreneur wants to get elected, the first thing he should do

is to get nominated. Nominations are made either by the corresponding Communist

Party committee, or collectively by lower-level deputies and individuals. Thus, nominated candidates are either "Party nominees" or "voter nominees" (Manion 2014).

-

By design, private entrepreneurs are usually nominated through the first channel

Party nomination.

For example, among the 700 seats at a provincial people's congress, 100 seats

are directly nominated by (allocated to) the Communist Party Committee.

The

remaining 600 seats are allocated to those voting districts (i.e., Prefectural and PLA

units) at the next level within the province, and the Communist Party Committee

in these districts then decides how to allocate those seats. If a prefecture is allocated

60 seats among the 600 seats, the prefectural Communist Party Committee would

directly nominate some candidates and then distribute some seats to the voting

district at the next level down - the districts and counties.

After several rounds

of distribution and allocation, a county might receive a number of allocated seats.

Assuming that a county receives 5 allocated seats, it is a given that one seat would

go to a local party or government leader, presumably the county Communist Party

secretary or the county head, and one seat would go to a female candidate, and three

remaining seats can be up for grabs (Interview G151). If a private entrepreneur is

thinking of running for provincial legislator, he should think carefully whether he has

a shot at one of the three seats, but if a female entrepreneur wants to run, she might

want to consider whether she has a good chance securing the female seat. All of these

strategic calculations and decisions are usually made by the entrepreneur candidate,

the election committee, the local Communist Party Committee officials (especially

those at the Organization Department and the United Front Work Department),

relevant personnel at local people's congress standing committee offices, and other

28

relevant organizations that might be involved in nominating candidates. As one can

imagine, a significant amount of informal lobbying is going on during the nomination

process. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this type of lobbying is highly costly and

informal -

and thus risky -

and getting nominated is only "step one" in securing

a seat in a local legislature.

In sum, to be elected as a provincial legislator for instance, a private entrepreneur

first needs to be nominated either by the provincial Party committee, a prefectural

Party committee, or a county/district Party committee, all of which make the final

nomination but receive recommendations from democratic Party committees, local

governments, and various organizations. After the entrepreneur makes it onto the

ballot, he will be voted on by the corresponding prefectural legislators. Since the

number of candidates is usually 20% to 50% more than the number of seats, an

entrepreneur candidate usually engages in some form of campaign to secure votes

and, in some cases, such a campaign entails bribery.

Becoming a legislator entails costs of various forms. As discussed above, there are

costs to lobby to receive a nomination and costs to campaign for seats. Apparently,

it is also costly after one becomes a legislator.

There are opportunity costs of

time spent on collecting public opinion information, writing legislative and policy

proposals, as well as sitting in meetings and social gatherings. Moreover, Sun, Zhu

and Wu (2014) have uncovered the high costs private entrepreneurs must bear to

socialize with other deputy "friends," especially with government and Party officials.

If the costs of being a legislator are so huge, interested entrepreneurs must be

expecting greater benefits in return. What are the benefits of holding an office in

the Chinese legislatures? The degree to which Chinese legislators influence law or

policy making is still debatable and certainly varies by region (Cho 2009; Manion

2008). Nonetheless, entrepreneur legislators enjoy preferential treatment, including

29

easier access to government contracts, credit and land; immunities when facing

prosecution; and, most importantly, access to an elite political network, which deters

local predators.

The Citizenry

Citizens are not involved in higher-level legislative elections but they directly elect

legislators at the district and county levels. Their political participation takes two

forms: casting a vote, and nominating individuals as "voter nominees." The cost of

the former is very minimal, and the cost of the latter is significant. Contrary to the

stereotypical image of citizens in a strong authoritarian state, Manion (2014) argues

that, at the very local levels Chinese voters can use their electoral power to select

"good types," i.e., Legislators who reliably represent local interests, by collectively

nominating candidates as "voter nominees." How Chinese citizens use their limited

power to influence electoral and policy outcomes is an extremely interesting topic

on its own, but in the case I study, private entrepreneurs are usually nominated as

"Party nominees" and not "voter nominees," and the role of citizens is minimal in

influencing Party committees' decision on whom they nominate.

The Signaling Mechanism

A lower-level bureaucrat extracts from local business when he considers it relatively safe to do so. Safe conditions are those under which the extracted business

does not have any means, most likely through personal acquaintances or the media, to report the extractive behavior to the superior of the low-level bureaucrat.

When an extractive local bureaucrat faces an entrepreneur, he calculates the costs

and benefits of rent extraction. If the firm owner holds a seat in the local people's

congress, what does it signal?

The status of local people's congress membership might signal a variety of things:

The business is likely to be an established and profit-making business in its industry;

30

it is probably a major taxpayer and an important job creator in the local economy;

and relatedly and most importantly, being a legislator signals one's connection with

local political elites. Through attending required plenums, collaborating in working

groups, and participating in legislature-related or other events, the entrepreneur

deputy expands his personal network to incorporate political elites who are also

deputies.

Friendship is not guaranteed but connections are made and enhanced

through these activities. Well aware that entrepreneurs who are legislative deputies

have access to this extensive network of political elites, including potentially his own

direct superior, a low-level bureaucrat will be particularly careful when making a

decision to extract or not. If he decides to extract an entrepreneur with a legislator

status, it is likely that the entrepreneur will contact relevant higher-level officials in

his PC network to report the extractive behavior. Obviously, the higher-level official

does not have the obligation to respond to such a report and he could choose to ignore

it (which could be the case especially if he ordered the extraction). However, since

the report comes from a fellow PC deputy, the higher-level official is more likely to

take it seriously and deliver a satisfactory response.

Besides signaling political capital, being a legislator also signals one's legal power

to formally supervise local governments. The most important measures the local

legislatures can take include the law enforcement examination and appraisal of local

governments. During an examination, local people's congresses form supervisory

groups and investigate problems. They can sometimes force governments to correct

problems but their enforcement power is not particularly strong (Cho 2009, 58).

A second supervision mechanism is through appraisal of government agencies and

officials. An annual performance appraisal is required at the local people's congress

standing committee, and local deputies can exercise "deputies' appraisal" when they

31

see fit.' 2 Compared with examination, appraisal has legally binding force: a local

legislature can dismiss officials if they fail the appraisal. There are an increasing

number of cases where local officials from a variety of bureaus have been dismissed

from office because of the appraisal procedure, although the total number is still

considered insignificant."

In theory, the status of a local legislature also signals

one's abilities to exercise supervisory powers, although in real life these powers are

infrequently exercised, and therefore, their potential use as a threat is minimized.

Strategies to Protect Property

The view of the state as "the grabbing hand" is not China-specific, as scholars of

business-state relations have identified violations of property rights by state agencies

in many transitional economies (Frye and Shleifer 1997). Friedman and colleagues,

using data from 69 countries (many of them developing economies in Eastern Europe and Latin America), find that entrepreneurs in countries with heavy burdens

of corruption and bureaucracy are more likely to go "underground" to dodge the

"grabbing hand." (Friedman et al. 2000). More nuanced country-level studies are

done on specific cases (Shleifer and Vishny 2002 Chapter 9; Gans-Morse 2013). In

these systems where property rights are weakly secured, how do firms fend off the

grabbing hands of local predators? Existing studies have documented various ways

private firms defend their property rights from expropriation by the state or powerful elites. In these cases, since formal protection is usually either unavailable or

ineffective, firms usually resort to informal means, such as:

12

For instance, see the "responsibility and power of the Zhejiang provincial legislature" document

at http://www.zjrd.gov.cn/portal/Desktop.aspx?PATH-cnzjrd/srdjg/rmdbdh/zq

1 3 For a comprehensive list, see Cho 2009(61).

32

Awl"kww'w-

, _ - ._

---

-

.1

1,

(i) Private or corrupt force. When formal institutions fail to function, one default

option is to resort to private force. One such example is the criminal protection

rackets and private security agencies that played a central role in property security in early 1990s Russia. Corrupt force includes protection rackets provided by

bureaucrats and law enforcement officials, which in Russia replaced criminal protection rackets by the late 1990s. Using state resources, these protection rackets

provided private clients with property protections (Gans-Morse 2013).

(ii) Forging informal connection and exchanges. Another commonly used method

is to resort to informal connections. Wank documented that in 1980s China, private

firms invited "backstage bosses" -

public officials -

to join their firms as advisors,

shareholders, and board members so that these bosses could assist their businesses

with information on business-related policy, lowering tax bills, and preventing government expropriation (Wank 1999)." Another important channel of connection is

kinship, which provides a framework for entrepreneurs to get access to resources (Ruf

1999). Entrepreneurs with relatives in government share similar privileges as those

who hired backstage bosses, one of which is individualized protection of property.

(iii) Delegated law. Private actors might also resort to strategies of delegated

law to enforce property rights. Non-state actors are the main arbitrator in this

strategy. Business associations are one example of such a non-state actor. In the

late medieval period, merchant guilds served as an institutional mechanism to protect merchants against abuses by city governments. Such protection was achieved

through merchants' coordinated punitive actions against predators (Greif, Milgrom

and Weingast 1994).

In a similar fashion, by establishing norms of transactions

among members and sorting out disputes when necessary, business associations in

14

These "backstage bosses" can still be observed in the current Chinese economy. In 2011, 49.3%

of all SOE firms listed in the Chinese stock market have hired retired government officials. See

http://www.infzm.coni/content/60155 for a report.

33

Russia provide property security exclusively to their members (Gans-Morse 2013).

(iv) Partial ownership. Firms sometimes creatively construct ownership structures and forge sponsorships that protects their property and property rights. For

instance, in China, "backyard profit centers" of state agencies are entities registered

as independent public enterprises managed by incumbent or former public officials or

persons they trust. These relatively undocumented entities receive favorable regulatory and funding treatment from or with the help of their government sponsoring

agencies and de facto state protection for their private property rights (Lin and

Zhang 1999). In the 1990s, entrepreneurs could also seek partial local government

ownership of their businesses, which helped limit state predation (Che and Qian

1998; Oi 1992). This method of ownership disguise ceased to be necessary when the

private sector was officially recognized as legal (Tsai 2007).

In present-day China, private entrepreneurs have a toolbox of strategies to protect themselves. They still actively engage in informal connections and exchanges

(Kennedy 2005); they sometimes use political connections to facilitate use of courts

(Ang and Jia 2014); they creatively register themselves as foreign investors and use

"round-tripping" to avoid heavy taxation and regulation (Xiao 2004); they continue

to partner with state ownership and foreign investors (Huang 2005); they obtain

CCP party memberships (Dickson 2008); and they resort to organizations such as

business associations (Kennedy 2005).

In this dissertation, I do not attempt to

argue against any of these studies or dismiss any of these strategies as ineffective

or unimportant. Instead, I am proposing an important addition to the "toolbox"

of strategies: Chinese entrepreneurs, in addition to using many informal coping

strategies, join legislatures to protect their property from predation.

I argue that this strategy is different from other strategies in the following respects.

The first distinction is its formal nature.

34

Compared with other strategies that

heavily rely on political connections, the strategy of using legislative membership to

protect one's property can be purely formal. An entrepreneur does not have to go

through any informal exchange to establish or enhance political capital once he has

a seat in the legislatures. A second distinction is its "low-cost" nature. Although

securing a legislative seat might incur high costs, once an entrepreneur has a seat in

the legislature, his position serves as a signaling mechanism without any additional

investment. On the other hand, other strategies such as forging informal connections

or relying on partial ownership can only be sustained through iterated and costly

interaction between entrepreneurs and other parties.

Lastly, the focus of this project is on property security and not on property rights

formation, yet the strategy of using legislative office to protect property has implications that go beyond maintaining individualistic property security.1 5 If private

entrepreneurs in China become more influential and willing to advocate for reform

over time, they might challenge and ultimately change the function of legislatures,

increasing accountability and expanding and formalizing property security and property rights protection through legislation. I entertain these possibilities in greater

depth in the concluding chapter.

Alternative Frameworks

This project contributes to the literature on authoritarian institutions and the

political economy of property rights. Dominant theories in both literatures take a

"state-centric" approach, which assumes little individual agency, and in which firms

and individuals are mere takers of institutional arrangements.

15

The literature on emergence of property rights is also experiencing an ongoing debate regarding

the role of the state and the role of individuals. For a review of this matter, see Markus (2015),

Chapter 1.

35

How would state-centric theories explain entrepreneurs' participation in legislatures and their privileged position in regard to property security'?

One possible

explanation could be that the "entrepreneurs in the legislature" phenomenon is simply a state-engineered process. The state co-opts business elites by both giving them

political status and extracting less from them. "Less extraction" is one type of rents

individuals receive in return. Firms have no autonomy in deciding whether they get

a seat or not, as well as whether they experience predation or not.

Although this state-engineering theory would predict an empirical association

between entrepreneurs with legislator status and the severity of property extraction similar to what I establish, qualitative evidence suggests that such a stateengineering theory might not fully explain Chinese entrepreneurs' political participation. If these entrepreneur deputies were co-opted, we would not have observed

these entrepreneurs behaving against state interests.

Truex (2013) suggests that

NPC deputies exhibit a behavior pattern of "representation with bounds," reflecting

the interests of their constituents on non-sensitive issues but not on sensitive ones.

Politically sensitive topics include freedom of speech, association and the press;

political rights; multi-party competition; and high-level corruption, among others.

However, at the local level, I observe cases where deputies are active and outspoken on issues that are politically sensitive. For instance, in a district-level people's

congress located in a coastal province, among the 301 policy proposals from private

entrepreneurs between 2007 and 2013, 37 were sensitive or contentious proposals."

One proposal asked the local government to "resolve land disputes now" and "give

back land to rural residents" (Proposal S 119-2012), while another entrepreneur proposed that "better compensation policy" is needed for relocated residents "whose

1 6 Similar to King, Pan and Roberts (2013) and Truex (2013), I define issues related to democratic

reform, threatening the legitimacy of the central or local governments, and collective action as

sensitive issues.

36

houses are torn down for development projects" (Proposal S39-2012).

Another

provocative entrepreneur demanded "real district-level self governance" (Proposal

S35-2013). Not being co-opted, entrepreneurs sometimes propose potentially genuine opposition and progressive reforms in the legislature.

A second state-centric argument would be a "state capacity" one. A local government expropriates businesses more heavily when local revenue is low or when

expenditure is high, and goes more easily on them when local revenue is abundant

or when spending is low. Consequently, a local government decide on the numbers

of entrepreneurs to include in the legislature, reflecting either stronger or weak reliance of the local government on entrepreneurs. Similarly, a revised version of local

state corporatism theory argues for a fiscal dependency theory: Local governments

increase their credibility of property security in the eyes of investors by raising taxes,

so that the government is more dependent on the revenue these local business provide (Lewis 1997). These state-capacity hypotheses are theoretically plausible, but

they are not supported by macro-level evidence in the Chinese case.

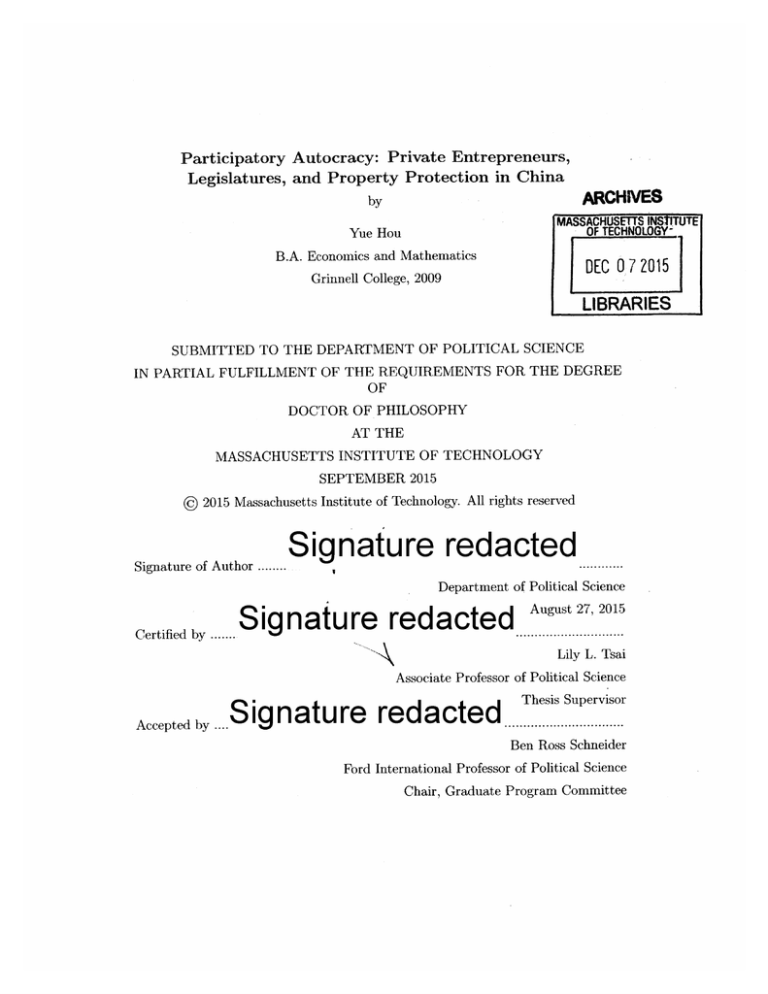

Figure 1.1

plots the prefectural-level extraction rate against local government revenues (left)

and against local government expenditure (right) between 2002 and 2006. The flat

lines suggest that there is essentially no correlation between government revenue (or

expenditure) and how much local government extracts local business in a given year.

Therefore, the state-capacity argument is not supported.

37

Fig 1.1: Local extraction vs government revenue /income

0O

0

0

0

0

10

14

12

Governent

00

000

0

00

0

0

1

0

0

0

11

12

13

14

15

16

Go~ommen Exponditure

Revenoo

Note. The first graph plots the bivariate coirrelation between prefecture-level governent revenue (logged) and average local extraction level. The local extraction

level is calculated as the average of extractive payments of all surveyed local private

entrepreneurs in a given prefecture and a given year. Similarly, the second graph

shows the bivariate relation between prefecture-level government expenditure and

local extraction level. The flat lines suggest that there is no correlation between

government revenue (or government expenditure)~ and local extraction level. Extraction data is from ACFIC 2002, 2004, and '2006 surveys. See subsetion Data for

more details about the ACFIC survey. Government revenue and expenditure data

Yearbook.

is from China Statisti

Observable Implications

After establishing the core assumptions of the model and elaborating the lpreferences of the key actors, now I nmove on to the observable implications of the theory. If

the system funictions as described, private entrepreneurs compete for seats a~t local

legislatures to protect their property from being expropriated by lower-level bureaucrats;

lower-level bureaucrats expropriate local businesses, but avoid those who

have seats in the local

legislatures; higher-level officials interact with entrepreneur-

legislators and collect information on lower-level bureaucratic behavior.

One

observable implication is a particularly obvious one: Private entrepreneurs

believe that a seat in local

legislatures protects their property from expropriation.

38

hwww" "_ - -,

- -

s , . , I-

-

---. 111.

_ 1. 11---

"Aww"V"iw

-"

-"

kii

-

, -L-Awki

_-

-_--1

Most entrepreneurs probably have multiple goals to achieve after joining a local

legislature, but my theory would suggest that the main motivation for them to

compete for seats is property security. I closely assess this implication in Chapter 3.

The first implication deals with "motivation," and the next implication deals with

"effectiveness." If the strategy of using legislative office to protect property is an

effective one, we would not only observe that private entrepreneurs want to join

the institution, but should also observe that there are real benefits after an individual becomes a legislator. If such a strategy is in fact ineffective, there is no reason

entrepreneurs would bear high costs to compete for seats, after observing the ineffectiveness. Therefore, we should observe that entrepreneur-legislators are in fact less

likely to be expropriated by local bureaucrats, compared with their peers without

political status. I assess this observable implication in Chapter 4.

Finally, I closely examine the mechanism of the property protection strategy. My

argument suggests that legislator status signals political connections and thus deters

expropriation.

If a seat in local legislatures indeed signals political network and

prestige, bureaucrats should treat individuals with connections in local legislatures

with preference. Chapter 5 explores this implication in greater depth.

Data

My argument on authoritarian institutions and the private sector is broadly comparative, but the empirical evidence is drawn from the analysis of aggregate and

individual-level data for the case of China. Contemporary China provides an ideal

setting to study the role of authoritarian legislatures. With a population of 1 billion citizens who are eligible to vote in county- and district-level legislative elections,

China has the largest "electorate" and is one of the most politically significant among

authoritarian regimes. Also, the institutional arrangement of Chinese legislatures

39

k96

resembles many contemporary authoritarian regimes. Examining institutional settings and incentive structures within the Chinese context is therefore conducive to

both theory building and empirical testing.

As Tullock (1987) points out, collecting information on autocracies is highly challenging, and as a result, data is usually sparse and poor. Researching contemporary

authoritarian China is no exception, and data quality in China presents a real challenge. 7 I collect information on Chinese legislatures, private entrepreneurs, and

their strategies to protect property through a mixed-method approach, combining

quantitative survey methods with 106 in-depth interviews and two field experiments.

Each method covers a variety of regions in China. I supplement these materials with

official documents, news reports, and secondary sources from existing research. The

chapter appendices provide additional details: on the implementation of interviews

(appendix to Ch.3), on the surveys (Ch.4), and on the experiments (Ch.5).

To understand the business environment of private entrepreneurs and state-business

relations in China, I conducted 106 in-depth interviews with Chinese private entrepreneurs, government officials, scholars, and journalists during 16 months of field

research between 2012 and 2015, across five provinces in China. These interviews

were arranged through a combination of local government and academic contacts, as

well as my own solicitations. All interviewees were guaranteed anonymity. These interviews were semi-structured, and each lasted between half an hour to a few hours.

The five provinces and prefectures Beijing -

Zhejiang, Guangdong, Hunan, Guizhou, and

were selected to reflect important differences between coastal and in-

land provinces in terms of economic and private sector development, as well as

regional differences in institutional arrangement and government capacity.

Zhe-

jiang and Guangdong Provinces, located in coastal China, are the richest provinces

17For

discussions on data quality in China, for one example, see Tsai (2009).

40

in the country, 18 and both have a developed private sector. Local governments in

these provinces have reputations for being "business-friendly" and "service-oriented."

On the other hand, Hunan and Guizhou Provinces, located in central and western

China, have less sizable economies and less developed private sectors. Governments

in these provinces are reputed to be more aggressive and less friendly towards businesses.19 I also spoke with local scholars studying similar topics in Beijing. These

in-depth interviews not only helped me develop a deep understanding of everyday

business-state interactions and a theory of property protection in the Chinese context, they were also invaluable in identifying broad patterns and scope conditions

for my theories on property protection in transitional economies.

After developing a basic understanding of business-state interactions based on observations in these locations, the next step is to make generalizations about private

entrepreneurs and property protection for a broader.range of locales. A nationally

representative survey of private entrepreneurs allows me to exploit variation of entrepreneurs' political participation in China across not only space, but also time and

industry. The survey was conducted every other year jointly by the All China Industry and Commerce Federation (ACFIC), the China Society of Private Economy

at the Chinese Academy of Social Science, and the United Front Work Department

of the Central Committee, and the Communist Party of China ("ACFIC survey"

hereafter).

The ACFIC survey sampled private entrepreneurs from 31 provinces

and among all major industries, and it is by far the most commonly used Chinese

private entrepreneur survey by scholars (e.g., Ang and Jia 2014; Li, Meng and Zhang

2006; Sun, Zhu and Wu 2014). In the questionnaire, private entrepreneurs' political

status, as well as their personal and business background, was asked. Importantly,

entrepreneurs responded to the question of how much expropriation by local govern18

Phoenix Finance News (Chinese) http://finance.ifeng.com/a/20150202/13475261_O.shtml

19

For one example, see Institutional Indices in Li, Meng and Zhang (2006).

41

ment they have experienced. Direct interviews were conducted using a questionnaire.

The richness of this dataset allows me to analyze the determinants, the severity, as

well as variation of local-level expropriation. The survey also provides important

information on private entrepreneurs' political participation in a variety of political organizations, including the people's congresses, people's political consultative

conferences, and other government affiliated organizations and associations. Such

data allows me to compare the effectiveness of political participation in different

channels.