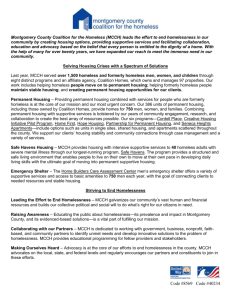

Reaching Home A Guide for Expanding Supportive Housing in

advertisement