Document 10467336

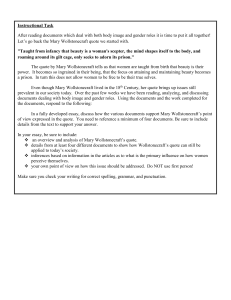

advertisement