Document 10465515

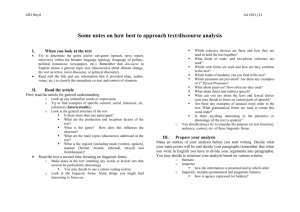

advertisement