Document 10464670

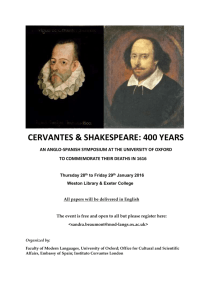

advertisement