Document 10464614

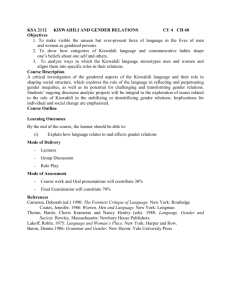

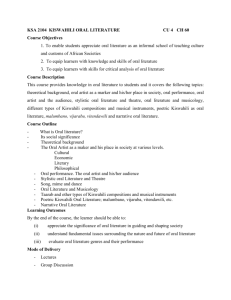

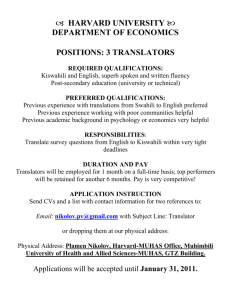

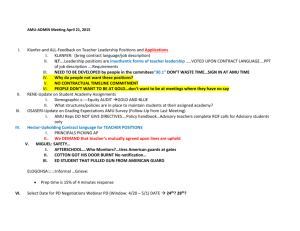

advertisement